Maria Thomas of Interrupting Criminalization reflects on the importance of health justice in abolitionist organizing, the Black Panthers and Young Lords, and her work to bring together healthcare workers and organizers to craft solutions to end the use of the healthcare system as an extension of the carceral state.

At the 2022 AMC Abolitionist Network Gathering, I had the joy of co-facilitating a session on Health Justice and Abolition with my friend and comrade, Fabián Fernández, as two organizers with the Beyond Do No Harm (BDNH) network at Interrupting Criminalization.

BDNH is a network of US-based health care providers, public health workers, advocates, and organizers committed to reproductive, gender, migrant, health, and disability justice working to interrupt the criminalization of pregnant people, parents, migrants, trans people, HIV affected people, disabled people, and people in the sex trades in the context of accessing care.

The Network Gathering was held four months before BDNH released 13 principles for providers to interrupt criminalization –– something we’d been workshopping behind the scenes for a couple of years. And so it offered the perfect opportunity for a soft launch: to gauge interest in the principles, recruit interested folks to join our work, and let participants know about the monthly sessions we’d be hosting in 2023 for health care, public health, social workers, and other health practitioners to learn about the principles and how they might implement them.

In the year since the Network Gathering and the 9 months since the BDNH principles were officially released, so much has happened. I offer some reflections below on the necessity of understanding organizing for health justice as an essential part of abolitionist organizing, along with some takeaways from bringing people together every month for conversations on what it would mean to transform these systems from within and without.

We’re in a critical window where people are more open to being enraged, engaged, moved, and radicalized around criminalization in the context of accessing care.

-

There’s a growing understanding of how Soft Policing (which, to be clear, is anything but “soft”) works and the immense harm traditional “helping professions and services” engage in.

-

Increasing numbers of health care workers, public health students, nurses, social workers, and medical trainees understand that the profession they entered is not what they imagined it would be, and they want to do things differently. The untenable conditions of the pandemic are hastening this realization.

-

We know that health care workers are hungry for analysis and strategies for resisting criminalization in the context of care –– particularly as abortion care and trans health care are increasingly criminalized –– because in less than a year, and just through word of mouth, over 340 health practitioners and organizers have signed on to the principles through our website; 1200+ people have attended an event focused on the principles or joined our listserv; and more and more people within our network are forming “pods” –– groups of people in relationship with each other (usually geographically proximate) committed to learning and taking action to interrupt criminalization together in their community or workplace.

People want community and organizing spaces where they feel a sense of belonging

-

The #1 reason people give for attending BDNH events is that they’re looking to connect with other health care workers and organizers who are fighting back.

-

Time and again, people tell us that the greatest gift of BDNH monthly sessions is knowing that they are not isolated and alone in the realities they face. Health care workers share with us how they’re inspired by, supporting, and learning from each other, and how they are braver together.

-

For example, network members are learning from each other about how hospitals sometimes perform “threat assessments” of patients, running their names to see if they have open warrants and then discharging them to police to be arrested, and how they can successfully organize against this form of harm. When a group at Mass General in Boston agitated to change their hospital policy and practice, arrests plummeted from thirty to zero in a single year. Each one of the lives affected by this change is precious. Each one of these interventions matter –– in some cases can be the difference between life and death.

-

In another session, Shira Hassan, Interrupting Criminalization’s Transformative Justice fellow, shared that “sometimes the best harm reduction we can do is to slow things down to understand what is happening, to not allow the system to crunch a “solution” onto someone.” That statement resonated with many participants. Our hope is that it will inspire them to engage in quiet but effective resistance within their workplaces, throwing creative wrenches into the maws of the system and undermining its ability to harm people seeking care.

-

The panelists who ground our sessions, the facilitators who hold down our breakout rooms, and session participants are always sharing resources and tools with each other, as well as imaginative ways providers can resist criminalization of those who seek their care. Health care providers who are at the beginning of their careers are getting connected to more experienced organizers and colleagues in their profession. Participants tell us that having a space that feels supportive to them has been hugely meaningful. As one participant put it, it “feels like the plants of resistance in my practice just got a deep watering, with a bunch of new little seeds planted as well. Thank you.”

Health care workers and others are organizing, AND we need more containers for sustained (not one-off) organizing.

It’s been exciting to see multiple organizing institutes and practice spaces for health practitioners emerge, and we’re hopeful that these will seed more autonomous health justice organizing, in workplaces and communities across the country.

To name a few:

-

The National Network of Abortion Funds has been holding an Organizing Institute for member funds.

-

Physicians for Reproductive Health has been working on more political education on decriminalization for their Leadership Training Academy fellows.

-

Healing Histories Project recently launched an Organizing Institute.

-

And in May 2023, a few hundred anti-capitalist, abolitionist & anarchist health care workers gathered in North Carolina for a convergence to collectively strategize around reimagining and undermining the medical-industrial complex. The values that the organizers of the convergence shared struck a chord with many health care workers, resonating with more people than the convergence could accommodate and generating a waitlist almost as long as the number who attended. These values bear repeating below and mirror the abolitionist principles for health care workers that a #CopsOutOfCare working group at BDNH c0-created, a sign that many of us are trying to build towards a shared liberatory vision:

-

We look towards a future that prioritizes collective care over individualized exploitation.

-

We honor expertise and undermine professionalism.

-

We believe that all humans should have access to knowledge of their bodies, unmediated by the hands of state and capital.

-

We work towards a future wherein all human and planetary life has intrinsic and non-exchangeable value, where we are able to live and die on our own terms.

-

We look to deconstruct the lines separating patient and provider and hope to collaborate on truly shifting the way power flows in these systems.

-

We need to think about the edges of our struggles not as limits but as the beginning of the next struggle as well.

This is a piece of wisdom that Ruth Wilson Gilmore shared in a Haymarket livestream with Naomi Murakawa in April 2020 that feels very relevant to organizing around health justice.

Thinking about the edge as an interface between current and future struggles, Ruthie says “first and foremost we should always plan to win. And if we plan to win, we should ask ourselves what happens next in the event of victory.”

As we gain more victories in interrupting criminalization through non-police and non-carceral street crisis response and non-punitive health care, as we refuse to call the cops and refuse to put people in involuntary psychiatric holds or other types of coercive control, we will continue to face retaliation in the form of attacks on our licenses, our communities, and our sources of funding. We’ve seen how the state has aggressively gone after organizers and bail funds supporting the #StopCopCity movement. We are also seeing attempts to prosecute family and community members who are supporting people in accessing abortions and gender-affirming care. We need to continue strategizing across funds and movements, anticipating and planning for future challenges in cross-movement spaces.

Looking back to move forward. Drawing on traditions of resistance.

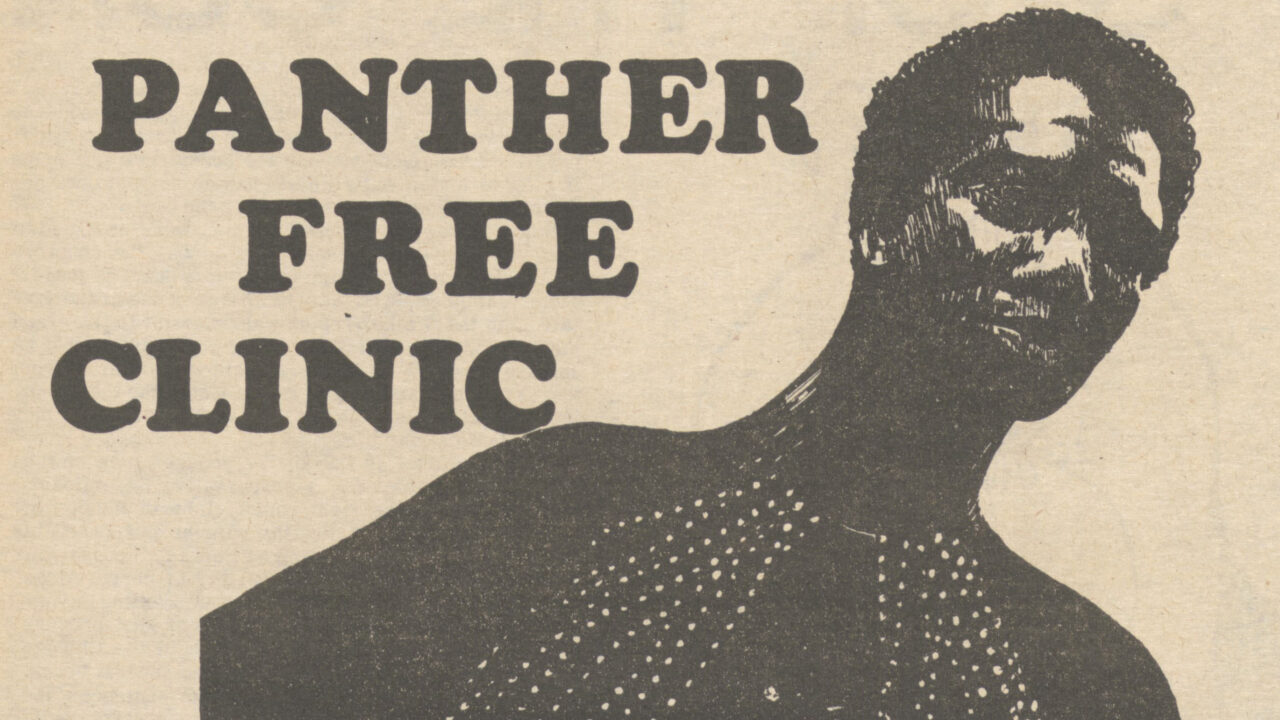

Our BDNH Principles draw inspiration from the work of the Black Panthers and the Young Lords to ensure free, accessible, and noncoercive medicine for the people, including by collaborating with the health care providers in the Health Revolutionary Unity Movement to commandeer mobile clinics and occupy hospitals. We are informed by the work of the Psych Liberation activists who worked with patients and physicians to break down the walls of asylums. We are inspired by the work of Sozialistisches Patientenkollektiv (Socialist Patients’ Collective, or SPK) which is brilliantly described in Health Communism. We learn from Liberatory Harm Reduction movements and Healing Justice Lineages. There are powerful traditions and lineages to build on and learn from, and there is much to be gained by studying about these lineages as we struggle together. It is in this spirit that we put together discussion guides and pod kits for groups wanting to engage in collective study and action to interrupt criminalization, and we plan to continue to research and share these histories of resistance. Because to win, in the words of the Black radical organizer, General Baker, “We have to turn thinkers into fighters and fighters into thinkers.”

For more information on the Beyond Do No Harm principles and organizing, please visit bit.ly/BDNHLaunch