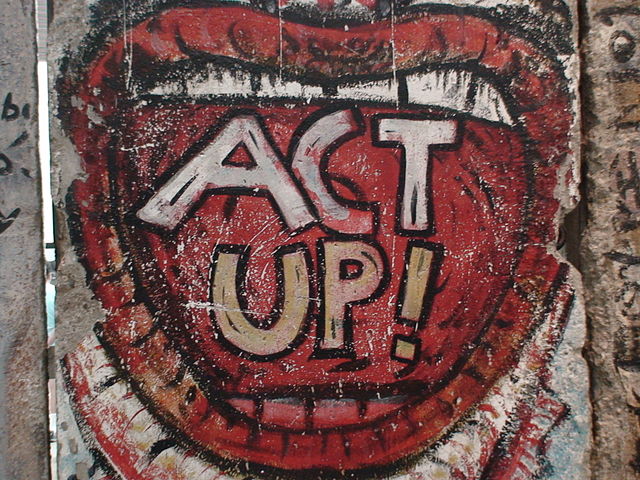

I met Jill Hurst in early 2019, over Zoom, to talk about the national effort that became the Athena Coalition. I’m now embarrassed to admit I had no idea who she was — an architect of the groundbreaking Justice for Janitors campaigns and, later, the director of organizing at SEIU. It was only in passing that I learned of her experience as a member of ACT UP, an experience I have come to see as invaluable for those of us trying to figure out how to organize megacorporations like Amazon. ACT UP’s nemesis wasn’t a megacorporation; it was a tangled mess of both public and private institutions, including the Reagan administration, the Catholic Church and the Christian Right, the pharmaceutical industry, and the criminal punishment system (whose criminalization of lesbian and gay sex, sex work, and drug use made fighting AIDS that much harder). After a two-day convening on the future of organizing megacorporations last fall, I sat down with Jill to ask her more about her time in ACT UP and the lessons labor might learn from it. We talked about the power of a militant minority executing culturally transgressive disruptions and what changing conditions can do to movement relationships. The interview has been edited and condensed.

Why did you get involved in ACT UP?

I went to school and was active in the gay rights movement at a time when people were not aware that they were getting infected. And so in very rapid succession, I lost a lot of friends. All of us felt really urgent, outraged, wracked by grief. The people in New York who began to do ACT UP were inspirational to all of us who tended toward organizing and direct action.

Up until then, there had been a lot of mutual aid stuff, and ACT UP was really the first more politicized view other than some sort of basic advocacy stuff. And so it was really a gift. It just gave us a path that expressed the urgency and anger.

I was your basic frontline activist: I went to big demonstrations, I shouted, I helped do support for actions. I was not a leader in any way.

What were you doing in labor at the time?

I worked for the American Federation of Teachers, Connecticut Affiliate and was a regular union rep. I negotiated contracts, I organized workers — mostly state employees and teachers.

What felt similar or different about union and ACT UP work?

They were definitely different. At the time, the labor movement was both really homophobic and pretty sexist. I felt like I definitely had good friends in the labor movement and really enjoyed my work there, but the more direct action part of my life at that time was not as much in the labor movement, other than during strikes. There were times when strikes felt a lot like we were doing what we were doing with ACT UP. That ACT UP street action was very similar to the sense of urgency and militancy of strikes.

Well, here we are, a generation later, trying to figure out how to take on megacorporations. When you think about your activism in the late ’80s, what links then and now?

One of the key things for ACT UP was how urgent it all felt and how desperate people were. And I think that [sense of urgency] is really important to create in other settings, but harder. During the Trump era — when we were all really fighting back because of the urgency of some of the horrible things he was doing — that felt closer to the ACT UP urgency, but not as many people were dying in quite the same way.

The ACT UP slogan was, “Silence = Death.” It doesn’t get more urgent than that. And I think the Black Lives Matter movement obviously comes the closest to that sense of urgency. But now, we are getting cut by multiple cuts. So Black and brown people are being killed, but it’s more: one and one and one and one. That makes it harder for the flashpoints to happen. When you think about the big corporations, they’re killing people too, but it feels more like they were a little bad, then they were a little more bad….

Sometimes in the labor movement, because there’s a lot of institutional risk involved, we want everything in this very planned-out, strategic way. And I think that also breeds a lack of urgency and a lack of recognition that things are really bad and people are actually suffering. Failing to act really does destroy people’s lives, either materially around them or actually causing some people to die. We don’t have that sense in very many of our movements. And some part of me feels like we’re awfully comfortable and we would be better off really steeping ourselves with people who are actually impacted in a way many of us as individuals aren’t.

We really need to look for moments where you can create urgency around something big corporations are doing or the possibility of making a change and that’s much harder. But I think over the long haul, we have to have some version of compression. Partly workers can [create] compression when they strike or if we could get to multiple strikes at the same time. I don’t know whether we really can get to enough strikes to actually shut them down, but I think we could get to enough strikes to create a crisis that would force policy makers, etc., to act. I feel like small businesses are getting the death by 1,000 cuts as well. And I wonder, what is the way to make that kind of all come together in a moment of urgency?

Is there something about facing the odds head-on that can help?

The truth is, we increasingly have such a small percentage of the workforce. We are at almost nothing, but it’s a little unreal to people, even though it’s true. And so I think in taking on big corporations, whether you’re a community or you’re workers or you’re environmental justice activists, the sense of — what’s our best thinking? — and having people talk about it and debate it and then just try. I think people must let go of the notion that there’s a sure bet, that this is the thing. Because I haven’t seen the “one idea” actually work. It just seems like usually it’s several good ideas and you try five, and three don’t work and two do and then you’re a lot closer. And I think at least in some of the unions I’ve worked in, people want one, single answer and everything is going to ride on that one answer. And I just don’t think that’s true.

You really need for people to engage and feel empowered – to bring their full selves to the fight. If that’s the kind of world we’re trying to create, we have to give people the opportunity to actually engage in that way. So you have to let workers design in some way their own fight once they’re engaged and committed and you provide some basic framing and ideas, but if they don’t, in the end, own it and run it, it won’t work. Not that it should all come from the bottom, but it equally should not all come from the top. And ACT UP was certainly a good example of relatively little coming from the top and I think the urgency helped a lot, but we didn’t have employers attacking people in the same way.

We had a deadly disease, which is worse, but it isn’t the same as having an employer that’s going to come down on people. And so there are things that the central staff needs to have happen in a fight against a big corporation, but there’s a lot of room to let a thousand flowers bloom and encourage people to feel empowered and to work together to figure stuff out versus being told what to do. And I think it’s sort of the nature of institutions that we try to tell people what to do. The more we’re structured and there’s a hierarchy and people are elected, they deserve to have authority. They should provide leadership and vision and all those things that are important, but it’s also really important to let people figure out how to fight once they’ve decided to be committed to the fight.

ACT UP never represented everyone or even the majority of people who had HIV or AIDS or was personally touched by HIV or AIDS. And certainly now, unions and worker organizations hardly represent the majority of people who work for a living, let alone within the confines of any one of these mega corporations we might be talking about. I’m hearing a lot about the power that a militant minority can have and also the need for that militant minority to have critical mass.

We get lucky when we have an already organized shop and we can strike and have everybody, but for global corporations, having the majority across the globe is very hard and any individual shop doesn’t have enough power relative to the corporation. So it would be great if you could have a majority worldwide. I just think if we wait till we have that, we will never be able to act. And so I think that there is a really important role for a smaller group that is willing to do more in order to disrupt the status quo and create urgency in a way that forces policymakers and bosses to act. And without that, it’s very hard not to just be basically a lobbying operation, and the big companies have too much money and too much power in our system for that to work. You need people who will disrupt the status quo, both for the politicians and for the corporations, whatever the target corporation is. And that you can do with a minority if you’re smart about where you have that minority.

At the same time, I do think there are other things that can happen that can build broader support because the politicians and policymakers and the companies pay attention to what the public thinks. And so the other thing that was happening while ACT UP was defining the left militant wing of stuff is we had very well-respected people getting sick — beloved actors, etc. And it was beginning to change people’s sense of who this disease was affecting. ACT UP was just one piece of a lot of things happening around AIDS.

In order to take on any big issue or big corporation, we need all those things happening or at least as many of them as we can put in motion, including things that move the hearts and minds of the majority, but it doesn’t have to be a majority of a work site. As a labor movement, we often too narrowly define where we’re trying to find our majority and how. And that’s what I think ACT UP and the overall AIDS movement could show us, but so could the women’s movement and the Black Lives Matter movement, which has really done a brilliant job of both having militant actions and a lot of open discussion about what’s wrong in society.

What are some of your thoughts on the end of ACT UP, once the urgency began to recede? Who got left out?

It became the stuff of the policy crews of the world, which are great and they do some great stuff, but it wasn’t about action. So people like me, we don’t have a role in that anymore. I mean, you could call your legislator or whatever, but it wasn’t showing up to turn your back on an archbishop.

Some people went, some stayed. I just had a friend die who did AIDS housing for her whole life and never stopped being an advocate. But there hasn’t been huge numbers of direct action stuff happening since the cocktails came. The IV drug community has been left out time and again on treatment and systems, and there’s still a fight now about access to the medication to stop you from getting HIV. And then if you think about Africa and the globe, there’s still real problems.

When the insiders begin to think that their power resides without action on the street is when it really falls apart. I think once people get to being in those positions, we forget that you actually still have to do the other piece of the work, that they can’t do anything without militant action in the street against these corporations. And all too often when we’re in positions of power — I worked in the DC union world — we think that the power is ours when in fact it’s really important that it not be ours in order to actually drive change. And so when I think about campaigning against big corporations, I think about: how do you build street action that’s real and urgent and militant in a way that can play bigger than the actual size of the action because I never think we have enough people? You’re not going to get the Amazons of the world to just concede because somebody meets with them and the policy makers in a small room. But you could, if you were having mass disruption of the supply chain or the cloud or whatever, then force people to take action. And then the people who had access to those rooms would be really powerful, but they’d be restricted by what they could do because they can’t actually control what’s happening on the street in a one to one.

ACT UP was a place where there were tons of different people in motion. And that’s worth thinking about regardless of where people’s activity comes from. If there are some things we share, what are those? And what can I learn about how you move through the world that might help me get closer to the vision I have about what the world should be? The urgency of ACT UP forced us to do that. Nobody was really going to be turned away. And I think a lot of other times, I at least, am much more judgemental about who I’m willing to work with and in what way and whether anybody has anything to teach me. And in thinking about those days, I didn’t care as much. And in some ways that was better.