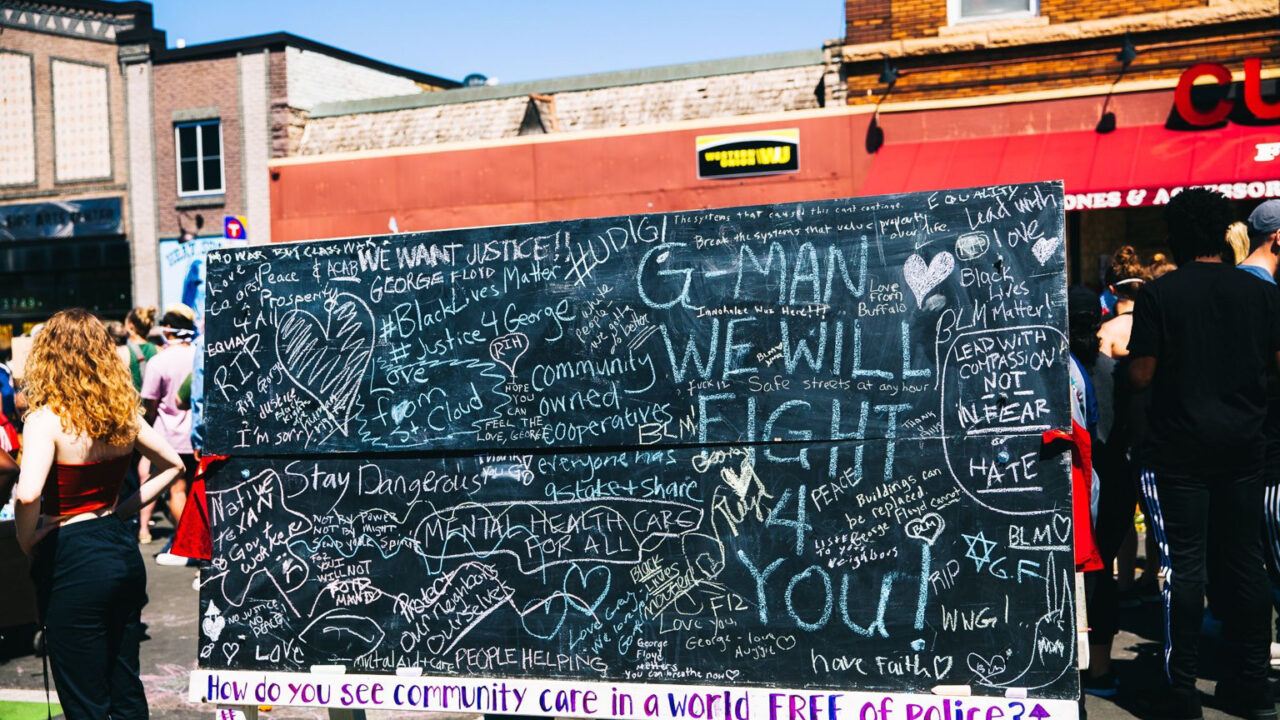

The firestorm of protest sparked by the murder of George Floyd by the Minneapolis Police Department was historic not only because of its scale – 15-20 million people participated in protests in the U.S. alone — but also because it shattered the commonly accepted belief that the police are the necessary cornerstone of public safety. Police abolition has become the rallying cry against racist police violence in the face of a century of failed reforms.

The uprising has sent local governments, mainstream reform groups, and funders scrambling to push through a flurry of procedural reforms that they insist can return the police to their supposedly humane mission. These are the same reforms — civilian oversight, residency requirements, de-escalation and mental health training, diversity hiring — that have failed for a hundred years.

One proposal deserves distinct analysis, due to its momentum in leftist circles: community control of the police. Community control proposals involve dividing cities into local police districts, each with a locally-elected community board (though some versions call for a randomly-selected board). Each board would elect one of its members to a larger commission. Together, these bodies would oversee police department policies, budgets, hiring, training, and discipline.

Supporters of community control start with a scathing analysis of the police that any abolitionist could get behind: its roots in maintaining chattel slavery, its brutal enforcement of white supremacy, and its continuing role as violent protector of the status quo. But instead of calling for the elimination of policing, community control supporters insist that the police can be repurposed into an instrument of community empowerment.

Appealing as the idea may seem from afar, a closer look shows community control to be deeply flawed. It is based on a misunderstanding of the structure and nature of modern policing; it is ahistorical, rooted in movement demands from an earlier time, before the experiences of newly liberated colonies cast doubt on the idea of “controlling” repressive agencies; it is especially vulnerable to co-optation; it seeks to replace the transformative vision of the abolition movement with a bureaucratic “solution” that would turn community leaders into police administrators; it assumes that community boards will support a progressive agenda; and it does not address the underlying causes of crisis, violence, and deprivation in our communities.

Instead of struggling to take over and redirect the master’s tool, we call for investing the resources now poured into policing directly into community initiatives whose core missions are about helping, healing, and sustaining people, not controlling them. Instead of a one-size-fits-all blueprint, abolition allows communities to imagine and build a world that centers community needs, taking into account local cultural traditions and existing programs and resources.

Easily undermined

Supporters of community control expect these elected (or selected) bodies to be inherently progressive, a questionable assumption. Getting onto such a board would be a tempting prize for all of the competing interests that swirl around any public body, such as police supporters, gatekeeper politicians and opportunists, as well as community activists of all kinds. Jazmine Salas of the Chicago Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression has argued that the commissions could be kept to a social justice mission by requiring (as with the Chicago version of the plan) that candidates have “two years of experience working toward the advancement of civil rights and social justice.” The Next System Project asserts, “the job of ‘qualifying’ community members for board service will fall to social justice organizations.” Demanding that candidates agree with your politics is not a credible basis for a public administrative body. Anyone politically active in communities of color, whatever their politics, can claim civil rights and justice as their banner. As the jury system shows, being from the community and being directly harmed by discrimination and police harassment doesn’t automatically protect us from internalizing a lifetime of pro-police education, TV shows, and the lack of real public safety infrastructure. As a result, there is a crisis of imagination, leaving many of those most impacted by failed reforms and over-policing to adopt calls for even more criminalization and punishment of marginalized and displaced people.

Another questionable assumption underlying community control proposals is about power. The reforms that these boards are supposed to enact — like making officers live where they work, more public access to records, better training, more selective hiring, a more diverse force, and civilian oversight of police discipline — are not new. What makes community control different, according to its supporters, is that these community boards would have the authority to enforce the reforms. But formal power doesn’t mean a lot in city politics. Mayors and city councils already have formal authority over police budgets and (directly or indirectly) over their goals and policies, but in reality, they haven’t held real power over the police since the 1980s. Actual on-the-ground power is exercised by the police departments and rank-and-file officers, backed by police organizations like the Fraternal Order of Police. The political elite that dominates city governments — which includes real estate developers, the hotel industry, banks, and sports franchises — is deeply supportive of a police force that serves its interests.

Elected officials might like to think they’re in charge, but they learn otherwise if they put it to the test. Following the police murder of George Floyd, for example, the Minneapolis City Council announced its intention to disband the police in favor of a new public safety department. That effort has been hamstrung by a slowdown by the police, pressure from business interests, and obstruction from the city’s charter commission. Police and their backers are preparing electoral challenges to remove all the council members. How would city governments, whose support would be necessary to establish the community control boards, provide them with a level of power that they themselves don’t have?

Community control would establish oversight bodies whose members would cycle in and out of office (however they are chosen) while the police force itself remains in place. This is part of the formula that gives today’s police (and their secret weapon, the police “unions,” which are free from public oversight) more power than the mayors, city councils, and chiefs they formally answer to. The Next System Project argues, “Randomly selected board seats, refreshed on a regular basis, make subversion of the democratic process virtually impossible.” But a steady stream of inexperienced community members does not add up to real power over an entrenched organization well practiced at eroding reforms, chipping away at oversight, and manipulating public opinion to protect its power. There’s nothing in community control proposals that would force the police to reconsider these tried-and-true strategies.

If your big demand is for a selection process to a new administrative apparatus, then you have no recourse if it is taken over or stripped down by those who oppose your goals.

Faulty analysis

When community control was proposed in the 1960s (and revived by the Black Panther Party in the early ’70s), police departments were still under the control of municipal governments, mostly run by corrupt political machines. The idea of putting the police under the authority of local community people was radical at the time, as it challenged the colonial occupation model of policing.

Partly in response to the militant movements of those years, the police system has gone through several phases of restructuring. In today’s world, police departments are one component of a highly integrated network dominated by regional fusion centers, private security companies, the Department of Homeland Security, federal agencies such as the FBI, DEA, NSA, TSA, and ICE, giant data-harvesting corporations, and an aggressive police technology and equipment industry. Additional “special jurisdiction” police departments are embedded in park and transit systems, universities, and airports. Big data policing — from facial recognition software to social media monitoring to ankle bracelets — is where the power is located in today’s system.

Some community control supporters dream of breaking up the police into smaller units that would be reborn as local people’s defense forces. It is difficult to see how they would accomplish this, given that they would be starting with today’s racist police structures, one of the system’s primary weapons of social control. If you want community defense organizations, abolitionists respond, then organize them! Leading the community into close involvement with the police is more likely to deliver us into their hands than the other way around.

Whose community?

Community control is touted as a way for Black and Indigneous communities and communities of color to place the armed presence of the police under local control. But what does that really mean? A one-size-fits-all approach would apply equally to thousands of white majority districts in which organized (or implicit) white supremacy could dominate, finding willing allies in existing police departments. And many of those departments could continue as they are. According to Max Rameau, of Pan-African Community Action, each district could vote to “keep their existing police department or start their own.”

Where’s the program?

Community control advocates are fond of claiming that abolition is a slogan without a program. This is far from true. The abolition movement, from the start, has defined policing as integral to the racial and class system it protects. U.S. policing was established with a mission of maintaining a permanent Black underclass, ensuring the exclusion of Indigenous people, and enforcing the obedience of the labor force as a whole. It can only be dismantled as part of a process of social transformation. Abolition is therefore a direct challenge to the exploitation the police exist to enable. The intermediate demand to defund the police calls for redirecting those funds to meet basic community needs. The plan is to invest in stable housing; education; a healthy, clean environment; respectful mental health supporters; and programs to prevent, intervene in, and transform the conditions that lead to violence.

In this way, abolition begins to address the crises of financial and emotional distress for which the police offer only punishment. By shining light on the connections between police harassment, violence, and other issues that impact people’s lives, we create natural alliances for the larger social changes that are urgently needed.

Under community control, the level of police funding would be left in the hands of boards whose politics might fall anywhere. With no program for addressing systemic injustice, the “community controlled” police would be left trying to manage the fallout from a system that creates deprivation and crisis.

A first step?

Underlying the community control proposal is the assumption that the police can be administered away from their historical mission.

“You can’t abolish unless you first control,” asserts community control leader Frank Chapman. After all, argues Georgetown University professor Olufemi O. Taiwo, “nothing stops the community from firing every officer, hiring EMTs and tutors in their place, and directing resources toward mutual aid projects.” If you are creating new community institutions from the ground up, as abolitionists have proposed in cities like Minneapolis, you can, in fact, design it however you want and hire EMTs and tutors or whoever else you need. But if you are setting out to administer an existing (and deeply entrenched and well-organized) organization, you can’t just fire its entire workforce without cause.

The proposed process and nature of community control works against deeper change. A commission whose only purpose is to manage a single public department is inherently reformist. It isn’t the commission’s job to ask the community what it needs and awaken people’s creativity to come up with new solutions. Its mandate is to become deeply involved in the operation of the police department — a racist and misogynist paramilitary force historically hostile to human rights — and convert it into a community service organization.

Incoming board members would need to learn the workings of the police department, be briefed by its leaders, and ride or walk along with its officers. There would need to be board and commission trainings, orientation manuals, seminars, studies, and awards all devoted to deepening the connections between the police and the community. Commissioners would be responsible for the police budget and would have to weigh the need to fire harmful cops against the cost of hiring and training their replacements.

A response to Chapman’s claim might be: “You can’t control unless you first rescue.” At a moment when the very legitimacy of the police system is in question like never before, community control provides a strategy to re-stabilize police departments and convince our communities to give them another chance to become the opposite of what they’ve always been.

All of the organizing, legislating, training, voting, educating, and participating required to establish and maintain these commissions and achieve community buy-in would create new facts on the ground, ultimately establishing a new normal. Investing in these structures and practices encourages people to limit their imaginations to such questions as, “What kind of police administration do we want?” or, “How well is the community commission doing?” If they didn’t like the answers, the available solution would be to elect new commissioners. This is how the prophetic imagination of mass movements gets squeezed into the back channels of the system. It is not a pathway to abolition.

Real steps

What facts on the ground does the abolition strategy create? The movement’s goal is to disarm and dismantle the police and to build up vital community resources and support systems. The strategy of defunding involves transferring socially useful functions elsewhere and eliminating the core of repressive and racist ones.

This is a self-reinforcing process. With every step, the community experiences the benefits of effective programs and needed resources. Most importantly, it begins to break down the internalized dependence on the police created by their control of resources and their monopoly on crisis intervention capacity. Shifting the billions now tied up in the police/mass incarceration system ($100 billion spent annually on the police alone) won’t meet all the needs communities have. But it represents a giant step toward that vision and fundamentally challenges accepted beliefs about what is possible.

One criticism levelled at abolition is that, since the police are part of larger systems of oppression, there can be no getting rid of them without addressing those systems first, so we should try to control them instead. This, precisely, reveals the true power of the abolition demand. Starting from the immediate urgency of police brutality, it quickly becomes clear that more far-reaching changes are necessary. Given the cascade of crises facing our communities and our world, this is exactly the medicine that is needed.

Tactics and strategies

In response to abolitionists, community control backers warn that the system can’t be trusted to defund itself. This is certainly true. Victories are pried from the system through mass struggle and organizing, not by trusting people in power. These victories reshape the landscape for the next stage of struggle. By linking policing and mass incarceration with housing, health, education, and self-determination, abolition places itself firmly within the larger struggle for justice.

In fact, abolitionist and community control strategies both involve engagement with the system. Community control uses ballot measures, lobbying city councilors, and legislation to authorize commissions. Abolitionists pressure city governments to cut police budgets and support people-led programs. Both campaigns speak of encouraging our people to imagine a better future. We see that future as leading directly away from the police.

But the commissions and boards envisioned under community control can be restructured, downgraded, or eventually eliminated by the very government entities that authorize them in the first place. Any effective reforms could also be preempted at the state or federal levels. When midwestern towns started banning pipelines and sand fracking, state legislatures passed laws revoking their authority to do so. Such a tactic would be harder to use against a defunding strategy since setting municipal budgets is inherently a local government matter.

The movement-building potential of abolition was demonstrated this winter in Minneapolis. Abolitionist groups there spearheaded the creation of a People’s Budget, calling for investments in housing, public health, mutual aid groups, and harm reduction. The budget was presented with support from over eighty groups focused on racial justice, immigrant rights, labor, youth, religious communities, public health, gender equity, disability rights, and the arts. It was not adopted by the city (no one thought it would be), but the campaign resulted in an eight million dollar reduction of the police budget through the Safety for All amendment.

The question for organizers is not whether to engage with the power structure during the course of the struggle, or even whether we make intermediate demands along the way. The question is whether we are fighting for a goal worth winning.

The impact is being felt

Abolition is a radical idea that requires changing our imaginations about what is possible. That can be a hard fire to start but, once started, it is even harder to put out. Already, the abolitionist movement has delivered significant wins. Over the past year, multiple cities, such as Minneapolis, Seattle, Austin, New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., Portland, Baltimore, and Philadelphia, have passed significantly reduced police budgets, cut positions for officers to lessen community contact with the police, and created or increased funding of non-policing alternatives. In November, Los Angeles voters approved a requirement that ten percent of the city’s general fund be invested in social services and alternatives to incarceration, not prisons and policing. Some cities, such as Oakland and Portland, have seen entire units disbanded. Public school districts and universities have begun to sever ties with police departments in response to long-term organizing amplified by the uprisings.

Many of these are the self-protective moves we’d expect from institutions put on the defensive. Some are buying time in hopes of re-establishing a police or private security presence. That they feel the need to do so reflects the impact of the movement. In other cases, pressure from the street has sparked internal struggle and reflection. All of this is made possible by the enlargement of our collective sense of possibility. Until recently, the existence of the police was accepted as a given. It is now controversial. Abolition, only a few years ago dismissed as a pipe dream, is now inspiring organizing campaigns, research, and the development and expansion of alternatives.

Conclusion

Movements themselves can be teachable moments that expand our sense of what might be. They also change and adapt with the times. In the early 1970s, when the Black Panther Party proposed community control as a radical solution to police violence, the United States was just reaching the peak of its economic and military might, an upward climb that would come to a crashing end among the rice paddies of Vietnam. Today, we live with the results of the steady decline that has followed. Battered by the escalating inequality brought on by neoliberal policies, rocked by climate crises, Trumpism, COVID, and rebellion, the U.S. can no longer count on its founding myths to provide stability and must increasingly rely on its surveillance and policing apparatuses. The police, in turn, are openly and proudly embracing their role as the repressive iron fist of the system.

This is a time to sharpen, not blur, the lines of separation between our abused communities and the police that occupy them. A mass movement, spearheaded by energized and radicalized Black youth, has taken up the abolitionist demand, calling for the real and lasting change we need. This is a time to embrace our boldest vision and start making it real.

Click here to see a list of organizations that stand with this article’s call for abolition.