It’s commonplace to talk about “the root causes” of social problems, but few people are closer to the root than Miya Yoshitani. She’s been organizing the Asian and Pacific Islander community around environmental justice for over twenty years, starting with a campaign against Chevron in Richmond, California. As she points out, immigrant residents of Richmond, who spend their days breathing polluted air from the refinery, are literally living at the root of the extractive economy — the very place where profits are extracted from fossil fuels. Their lives play out “at the intersection of racism, poverty, and pollution.”

Miya and the organization she directs, the Asian Pacific Environmental Network, have not only mapped out the contours of the extractive, racialized capitalist economy, they have also thought seriously about how to build the alternative — a regenerative economy — and the narrative change necessary to make people think differently about their own decision-making power. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Jonathan Heller: It’s Juneteenth, so let’s start with a question about racism and racialized capitalism. How have racialized, financialized capitalism and the social order it creates led to the environmental justice problems you focus on?

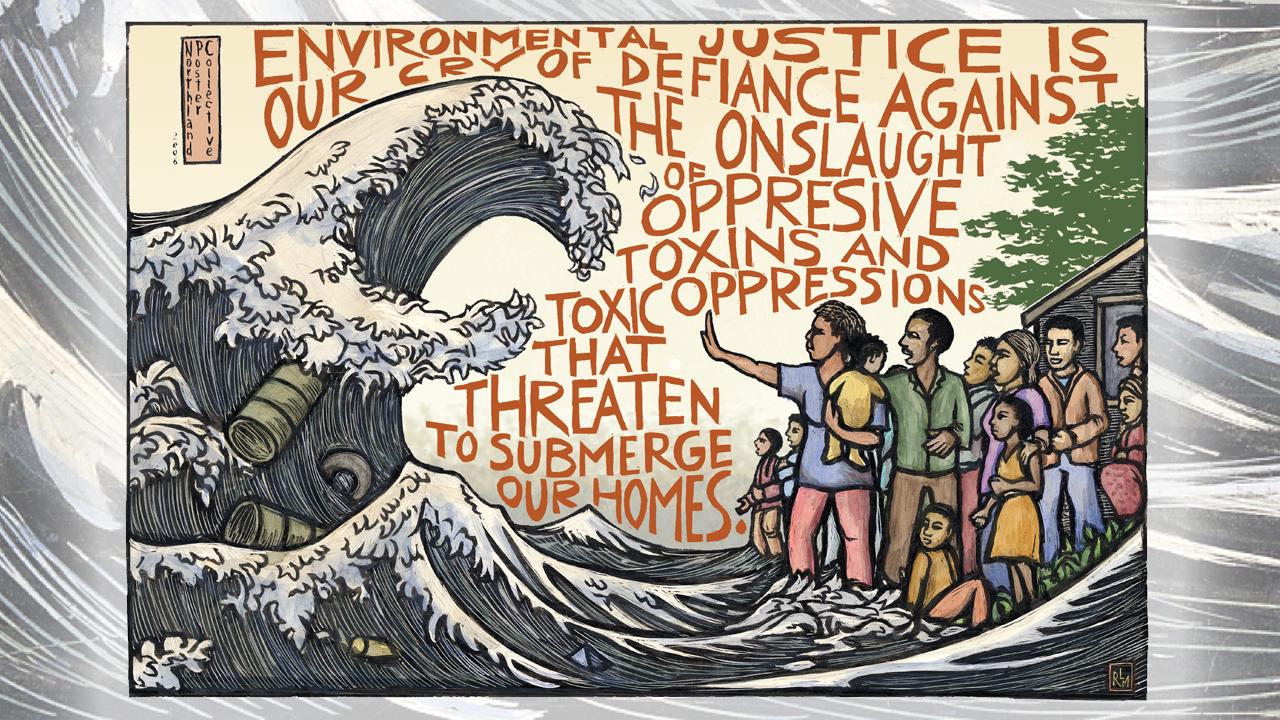

Miya Yoshitani: Our economic system is dysfunctional, and racism is one of its main enablers. Neoliberal financialized capital does what it does because racism allows it to. The burdens and benefits of our economy are segregated based on racism. Industry profits off of products like oil and gas and displaces the negative impacts on Black and brown communities and poor, working-class immigrant and refugee communities, like the one in Richmond. That’s incentivized by our economic system: profits for polluting are enormous and the economic benefits do not go to the people who bear the brunt of the pollution.

JH: How much of your work focuses on addressing the economy as a root cause of environmental injustice?

MY: APEN has always tried to address root causes at the intersection of racism, poverty, and inclusion. You have to address racialized capital and racism at their core. When you’re fighting for regulatory reforms, even if the campaign at the moment is only an incremental reform, you have to name the root cause.

More importantly, it’s evident in what our solutions are. While we might be working on a campaign around affordable housing or energy efficiency and its impacts on low-income communities, ultimately we always talk about the transformation of the economy that’s necessary for these changes to have a real impact. We’re always talking about long-term transformational shifts at the same time we might be saying we need a 20 percent reduction in this emission at our doorstep.

JH: Say more about the solutions and the long-term transformation you’re looking for.

MY: We talk about it in the framework of just transition, and APEN has been part of just transition work from the beginning. In the mid-1990s, the Just Transition Alliance started to bring workers — refinery workers and workers in toxic industries — together with fence-line communities who are not getting the benefits of those jobs to come up with long-term solutions for the managed decline of those industries. They joined together to answer the question, “How do we actually have a just transition?”

The whole economy is extractive. It’s literally extractive: industries dig up oil and gas from the ground and create a whole pipeline of destruction and exploitation and pollution that ends with tailpipe emissions. And the whole economy is based on the concept that your labor, your humanity, the land you live on, the air you breathe, the water you drink, are all resources to be extracted. Resources, health and well-being, and communities’ ability to thrive are extracted and driven to profit for industry. A restaurant worker providing the heart of the labor but receiving the least amount of the benefit: that’s extractive. Or the prison industrial complex that extracts the very freedom of Black and brown communities whose imprisonment creates profits for private prisons.

If we’re fighting against that expanded concept of an extractive economy, what is it we actually want? What do we want to replace it with? We call that the regenerative economy. Just transition is the transition from the extractive economy to a regenerative economy.

Judith Barish: How concrete are you when describing the regenerative economy?

MY: It’s critical to be specific about what a regenerative economy means because we need a mass movement of millions of people fighting for it to win. We’re currently limited in our imagination about what it looks like because we’ve been living in the extractive economy for our whole lives and for so many centuries. You have to paint a concrete, tangible picture so people can imagine what it would look like and how it would feel to live in a regenerative economy.

A regenerative economy is attentive to the local needs of communities, so there’s no “one size fits all” approach. We need an outburst of creativity and imagination to think about what it would look like in every community. Richmond is a community that has been so captured by the oil industry. We have to talk about what Richmond would look like, feel like, how people would experience it on a day-to-day basis if the extractive part of the economy was gone and replaced. We talk about clean renewable energy that is locally owned and democratically run. We reimagine the hard infrastructure that’s required, the way we interact with it, and the way it builds and recycles wealth in the community.

These fundamental values can be applied to everything. They can be applied to all the resources necessary to maintain a healthy community, like clean water, zero waste systems, zero emission transportation, local food systems and affordable housing. You can imagine what a regenerative economy would say about housing. Gentrification is happening, even in Richmond, which in the ’90s was a place people were trying to escape from because of high rates of crime and violence. Housing is getting more expensive and Black families are being gentrified out of multi-generational homes. What would regenerative housing look like? One of the answers is a land trust, collectively owned land that is generational, can never be privatized, and can never be exploited for profit. That is a key solution. We might fight for affordable housing or tenant protections, but, ultimately, to get to the regenerative economy, we’re fighting for collectively owned land that you cannot sell for profit.

JB: We’re in this moment of huge crisis and transition. The future is completely uncertain. How does that openness affect the campaigns you’re working on or the bigger question of how we remake our economy?

MY: In all of the pain and grief of this moment, one of the biggest joys is that it’s allowing us to reimagine what’s possible. These are the moments that our movements are built for. All the organizing has nurtured and created long-term solutions and this is the moment where there is an opening for change.

We’re seeing a dramatic shift in public opinion around policing, a centuries-old institution rooted in slavery. It has been intractable; the police, police unions, and the entire structure of policing have been able to maintain power all this time. Now, suddenly, there’s this dramatic opening where people are seeing we don’t have to live this way, and we don’t have to participate in this extractive and racist part of our economic system. People are out in the streets in incredible numbers, demanding things that even four or five years ago seemed impossible. Once people’s imaginations are cracked open and their hearts are open to what transformation can look like, that is an incredible moment to enter into.

We have the “shovel-ready” transformative ideas that have been waiting for these moments. If you’re open to transformation of one part of the system, you are more open to transformation to the rest of it. You can make connections between what’s happening to Black communities at the hands of police and what’s happening to Black communities at the hands of big oil companies or privatized healthcare or housing.

JB: Do you have examples of shovel-ready ideas to put into action in this moment?

MY: We helped pass a bill in the state legislature that created a billion-dollar investment in solar energy on multi-family affordable housing. It’s already on the books, and we could drive more public resources into it and blanket affordable housing with solar. The bill makes the benefits of transition to renewable energy accrue to both the owner of the rooftop and the renter underneath the rooftop and makes sure low-income families in that affordable housing see lower energy costs at the same time we are creating cleaner air in the neighborhoods. There are also a number of things in an experimental or pilot phase to expand on, like microgrids run by local communities.

Last year, Oakland City Council set aside twelve million dollars for a land trust in the budget. Think of what we could do if we had twelve billion dollars! We’ve been fighting to end the selling of public lands. If Oakland could build on public lands, instead of trying to increase funding for police by selling public lands, we could create affordable housing closer to transportation and jobs. We could maintain the right of communities to stay in upgraded, walkable neighborhoods. We could protect tenants from being evicted or having their rents increased. We could make those communities more breathable, livable, walkable, and more conducive to health, for people to thrive and benefit from the places where they live.

APEN is a co-founder of the Climate Justice Alliance, a national organization of environmental and climate justice groups rooted in local community organizing. The Alliance just put out a toolkit called A People’s Orientation to a Regenerative Economy with 14 planks for the just transition and dozens of shovel-ready policy ideas that people in different communities throughout the country have been working on: Black communities, Indigenous communities, and poor white communities like in Kentucky dealing with the unjust transition from coal.

JH: You’ve been talking about values, long-term goals and vision, the need to reimagine what things look like, and winning over people’s hearts in this moment. Those feel like parts of narrative change to me. How do you think about what you were just talking about being connected to narrative change?

MY: In the just transition framework we call that changing the story. It’s a critical part of how we get to a just transition. Ultimately, we have to change the story, starting with how individuals locate themselves inside the story, experience ideas, and imagine what’s possible.

Building parts of the regenerative economy today is critical to changing the story; you have to have a physical presence in local communities. People have to experience what it means to shift power in local democracy and decision-making, participate in imagining what they want and what’s calling to them in their hearts about how to make their lives and their families’ lives better, and experience collective power that changes things. This is an incredible moment for changing the story in people’s personal experience and that will create an opportunity to change the story collectively, not just about what we want today, but what’s possible and necessary for our future.

All these different strategies, all these elements of just transition, are tightly woven together. You really can’t move one without the other. We’re not going to get massive policy change and public resources in the right place without a massive shift in narrative, without a change in the way people conceive of their own ability to make decisions in their lives, their own imagination about the future they want for their kids, and their ability to personally impact that. So, changing the story from the neoliberal extractive economy to the regenerative economy is full of story, culture, and language. We have to create joy in people’s lives and encourage people to reimagine and dream.

JH: Can you talk about how that goal of changing narrative, changing those stories, has impacted the way you organize?

MY: Before narrative strategy and communications work became popular among social movements, we were doing things instinctively. You have to tell stories where people see themselves in it and you have to make sure the messenger is actually a trusted messenger, someone the community relates to and thinks of as part of their community. You don’t change stories by bringing in people from outside who use words and language people don’t understand.

Some of the first things we did in our organizing work in Richmond was bringing communities together to tell their story of arrival to the United States. How did you get here? What is the story of your journey to this neighborhood? That opens up pathways for people to relate their personal story to what’s happening to them now. Many of the stories of the Lao refugee community are stories rooted in war and violence: carpet bombing, Agent Orange, toxic contamination. They connect the extreme impacts of war to the health impacts of environmental racism. They tell stories about struggle and also about incredible resiliency and the triumph of getting to this new country. They talk about being isolated by language and culture, and then finding out the neighborhood you’re living in is causing your kids to have asthma. Your loved ones who survived a war are getting heart disease or cancer. People incorporate those experiences into a hopeful story about what fighting together feels like, what it could bring, and what it could mean for your kids and your future. We’ve always believed narrative change is an essential element of building power and building the solutions needed for systemic change.

In the broader culture, being able to tell the story of communities who are ignored and whose story is not represented is a critical part of changing the story for the rest of the country and changing how people understand their place in the extractive economy. In community organizing, we don’t use the same words — extractive economy — we ask people to talk about it from their own experience. We also create an environment that encourages an exchange of ideas by making music, telling stories, and sharing food. People make meaning through culture, in the experiences that encourage connectedness, happiness, joy, and inspiration. Those are critical parts of what community organizers do.

An essential part of organizing for systemic change is culture shift and narrative change. You can’t isolate it and take it out. Consulting firms that do narrative change and run campaigns by putting billboards up are completely disconnected from actual communities and their real stories. Not the right messenger. As a broader progressive movement, we keep trying to do narrative change in this dislocated way that doesn’t actually connect to people’s real stories. You can’t extract any one of these strategies from the rest of them. They all have to be integrated and talking about narrative change is a good way to talk about that.

JH: Is it possible for the left to come together around a unifying set of narrative themes? Is that an important goal in terms of breaking down silos and building more alliances?

MY: Aligning our narrative strategy across movements in an intersectional way is critical to winning. We won’t be able to win unless we are aligned as a movement.

Solutions and narratives need to come from the grassroots, up from the communities most impacted or closest to the problem. Even if you use the broad umbrella framework of just transition and moving from an extractive economy to a regenerative economy, each community needs to be able to talk about it in their own way and create their own dreams and new realities around it. Imposing something from the top down doesn’t work, and it’s not necessary. Everyone doesn’t have to use the same words, to talk about everything in exactly the same way. There are things that need to be consistent, like racial justice has to be at the core of the solutions. That’s something that can work anywhere, but people might talk about their experience in a different way.

JB: A common obstacle we face is people saying that we can’t afford the solutions we’re fighting for. What’s the narrative response to that?

MY: Yeah. The scarcity/austerity narrative versus the abundance/regenerative narrative. We’re up against that all the time. And within that, there’s also the competition narrative: if I win something, it has to come from somebody else. And the othering narrative that makes it all hang together: that we are in competition with each other and my survival depends on you not surviving or not thriving. Like every community, immigrant communities are inundated with those narratives, which tell us to feel fearful of others, Black communities in particular. That’s what breeds anti-black racism in immigrant communities. The fear that there’s not enough for everyone, you have to fight over the crumbs, and you need to align yourself with white communities and ride the coattails of white supremacy to get what you need. That’s all part of what makes the extractive economy work.

We’re constantly dealing with that in the environmental justice movement. It comes out as jobs versus the environment. If you want to survive economically you have to agree to a certain amount of poison in your life, literally. We try to crack open that assumption, turn it on its head, and change the expectation so people feel they have a right to a job that can support their family and allow them to thrive. People have a right to healthcare and transportation that’s accessible and affordable. They should not have to choose between living next to a freeway or being unable to afford the place they live. We can fight for a different economy that values jobs, health, economic well-being, mental and spiritual well-being, the intactness of culture, values, language, and creativity.

JH: We’ve heard a similar set of narrative themes in the interviews we’ve been doing. I think we can group what we’ve been hearing into five elements: radical structural inclusion; a ‘greater we,’ community, and solidarity; building agency, active democracy, and participation; markets serving people, we have enough to thrive, and we shouldn’t be commodifying things that people have a right to, like housing and health; and freedom to reach our full potential. Does that resonate? Does the just transition framework fit with that?

MY: I would add an ecological connection. The physical land, air, water, and essential resources have to be woven into it. Our physical environments are a part of how we attain liberated zones of wellbeing. We’re dependent on a healthy ecological system to survive and thrive. We learn over and over again from our Indigenous allies and partners that you can’t extract these ideas about freedom and liberation and democracy from the actual physical land that we are on.

JH: Is there anything else you’d like to add about your work and narrative change?

MY: The other thing hanging over my head is how climate change is going to further exacerbate existing inequalities. The just transition framework was developed to address the root causes of the problems that we are already experiencing. Communities of color, Black and brown communities, and Indigenous communities are already impacted first and worst by climate change. Living next to a refinery is like living at the root cause of the extractive economy, the root cause of climate change. People have to breathe that air and live in that neighborhood. You add the existing impacts of climate change: changing temperatures, more days of extreme heat, sea level rise, and the economic impacts of those, like the rising cost of energy and food. Then you have wildfires impacting communities that are being burnt to the ground and further impacting air quality in the Bay Area in the same polluted neighborhoods. And then you add poverty and COVID and state budget shortages and death by state-sponsored murder by the police. It’s all cumulative. It’s the same neighborhoods. It’s the same people who are impacted. And even more is coming. You can feel overwhelmed. I often do.

It’s important in these moments, when transformation seems possible, to go further and bolder in our fight for solutions. We have to find a way to tell our story that creates openings for hope and new possibilities rather than just despair and fear, othering, austerity, and retraction. We need moments of inspiration, envisioning a regenerative economy, living in abundance, liberated racial justice, and real freedom for communities.