Dorian Warren is the President of Community Change, one of the country’s leading community organizing projects, and a political scientist whose work focuses on race, class, and labor in the U.S. Dorian sat down with us to share his perspective on the dominant narratives in the country today. In the U.S., he reminded us, neoliberalism emerged in part as an effort by white Southerners to exclude Black people from the forcibly integrated public sphere. Racism and xenophobia undergirded attacks on the welfare state, from Reagan to Clinton. Today, they form the backdrop for the government’s insistence that low-wage workers return to work, no matter the risks. The narratives and logic of neoliberalism enable corporations and public decision-makers to justify prioritizing profit for the few over the wellbeing of working people and people of color. Dorian argues that we need to reclaim the narrative of freedom and fight for a Third Reconstruction in which we ensure that everyone can live a secure life. This interview, which has been edited and condensed, was recorded before the recent uprisings against police violence.

Jonathan Heller: Do you consider neoliberalism to be a root cause of the issues that you’re trying to fight and the crisis facing working people today?

Dorian Warren: Yes, and I would add a racial justice component to it. In the American case, we’re talking about a racialized neoliberalism that has created a crisis in a number of ways. One is ideological. At the narrative level, we face market fundamentalism: the faith and belief that markets will solve all problems paired with the delegitimizing of governments and collective governance as the solutions and a rejection of ideas of the public and social good. Two, at the governing level, we are starting to see a rush to austerity in the states — both the adoption of the ideological frame of austerity and the practice of it, as cities and states are further excluding and marginalizing people who need help the most. Three, another component relates to the role of capital in pursuing the profit motive. Large corporations, as employers, harm and hurt and (in this period especially) are killing ordinary workers in their workplace.

JH: How do the three levels impact people?

DW: If we look at the meatpacking industry in this country right now, for example, it is majority immigrant workers who are dying, literally, because of the profit motive and the market system that coerces people to work in unsafe conditions. Neoliberalism also delegitimizes governments, eliminates workplace regulation, fails to enforce existing regulations, and prevents regulations that will keep people safe: those factors combine in meatpacking plants to harm and kill people. And the underlying ideology is that, well, people need to consume meat! It’s full democracy for consumers, but authoritarianism at the workplace for workers, who have no voice or power. It’s all about the individual, so we have to force employees back to work with no regulations. Meatpacking plants are an intersection of neoliberal practice and the exploitation of immigrant workers.

I think about power in four dimensions: organizing/mobilizing power, narrative power, electoral power, and disruptive power. Right now, I think somebody should be running a huge campaign that brings together the workers who are being harmed in meatpacking plants. Is there a way for them to go on strike and be the disruptive power that challenges the corporate power of the companies and the broader industry, and then also disrupts the dominant narrative around notions of work and deservingness and what people need to survive? That would be a frontal assault on neoliberal ideology. Then, could you “electoralize” that by November, and build electoral power?

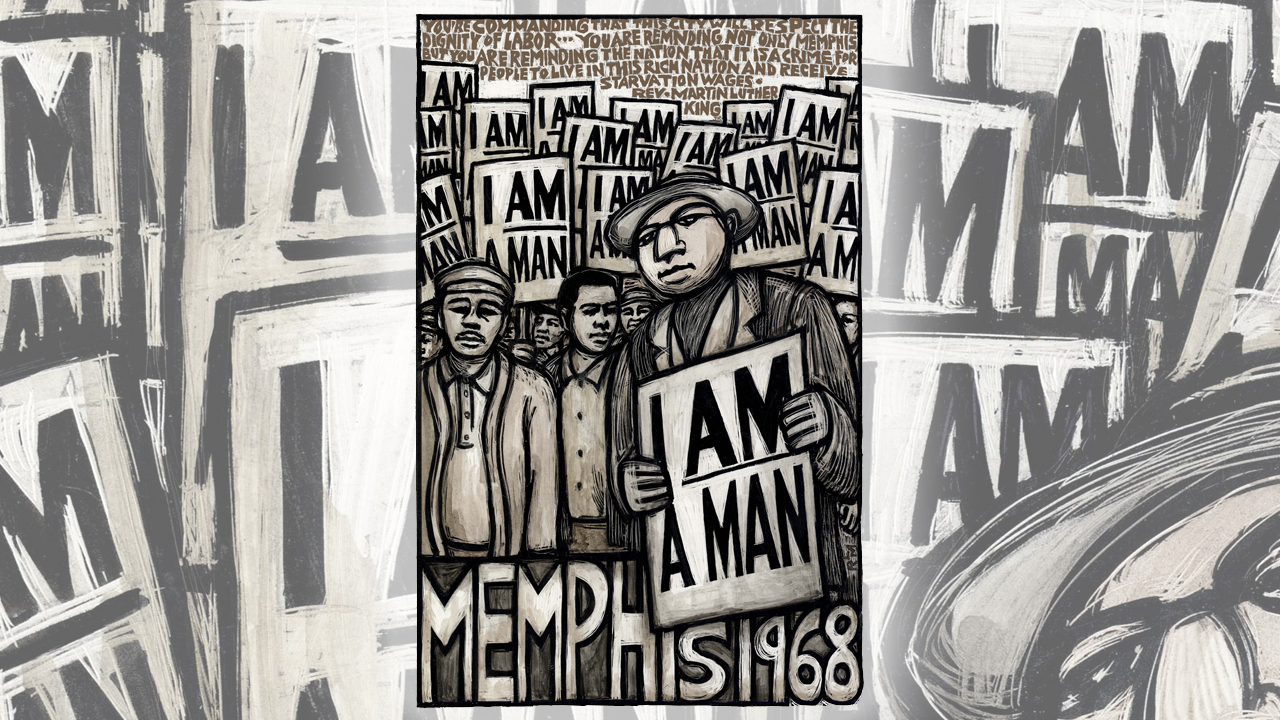

Something else made me think about neoliberalism in the U.S. There’s a typical story people tell about the origins of neoliberalism. At Bretton Woods or the Montpellier Society, economic elites got together and decided they wanted to throw out the New Deal, so they had to come up with a story that said, “government is bad, market is good.” I think that’s half right. But there’s another story about the origins of neoliberalism in the South of the United States that understands it as a part of white resistance to Black freedom. Neoliberalism was about marking off public space as white public space. Neoliberalism helped provide some of the narrative material to justify the exclusion of Black people from (white) public space at a time when there was a demand for integration. In essence, public goods were only for whites, individualism and segregation for Black folks. Nancy MacLean is a useful source on this. Those two strands — pressure from global economic elites and white, Southern backlash against civil rights — intersect by the ’80s and ’90s. You can see a direct line from the southern origins of neoliberalism to Reagan’s Welfare Queen in 1980. Remember, Reagan launches his campaign in Neshoba County, in Philadelphia, Mississippi, under the banner of states rights, in the very place where the young civil rights organizers Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner were murdered in 1964. The ideology of Reagan, reflective of the larger conservative movement backlash to both the civil rights movement and the New Deal, was essentially: “Your tax-paying dollars are supporting that racialized and gendered ‘other’ who’s not deserving, so we should eliminate government support. In fact, we should be coercing people to work.” That ideology became realized through policy with the 1995 “welfare reform” legislation that Democratic president Bill Clinton signed. And it is the same argument we’re having today about cutting off unemployment benefits for everybody in a time of a pandemic and economic crisis because we have to get “those people” to work, even if it results in sickness or death.

JH: What opportunities does the pandemic present in terms of changing or fighting the neoliberal narrative?

DW: It’s the biggest opening of our lifetimes in the midst of mass death. Instead of talking about the recovery, I propose we think about Reconstruction. In the period after the Civil War, the notion of reconstruction came from the need to reconstruct our democracy and our economy. Today, as we rebuild our democracy and our economy, maybe this is a chance to put some nails in the coffin of neoliberalism, in much the same way the New Deal put nails in the coffin of neoliberalism’s father, laissez-faire capitalism. This is going to be the decade of Reconstruction if we can organize well. And I do mean decade, not a two-week campaign or a six-month campaign or a two-year campaign. I’m borrowing from Reverend Barber because he has a whole book about The Third Reconstruction. If you think of Reconstruction after the Civil War as the first, the Civil Rights movement as the second, then maybe this could be a period of the Third Reconstruction.

JH: I like that. So one possible narrative is this idea of the social surplus. How would you tell the transformational story about the fact that the social surplus should belong to all of us?

DW: There’s two ways I can think of. First, what’s underneath the social surplus idea is the rejection of a notion of scarcity and the embrace of the notion of abundance. If I think about immigrants in this country right now, we’re stuck in a scarcity frame in terms of both resources but also in terms of public health. We have to close the border (they say) to protect everybody’s health. Talking about the social surplus gets us into the abundance frame. We actually have enough room for everybody, and we have enough to go around so that everyone can live a secure life — if we organize our society differently. Period. That’s a pretty radical shift.

The other example is talking about social surplus when we’re about to get an onslaught of austerity at the state and local level. How do we make the idea of social surplus real? Right now, we’ve asked the federal government to bail out states and cities. Great, now can we push it some more and get some other ideas on the table? How about the Federal Reserve offers no-interest loans for twenty years to cities and states? They offer low-interest loans to banks all the time to prop up the financial sector; can we imagine them doing that for states? Ideas like that could help us escape the austerity frame, bring in a social surplus frame, and reset the terms of the debate.

Judith Barish: We seem to have accepted this idea that creativity and innovation and problem-solving are private sector capacities, which the public sector can’t manage. How can we take that on?

DW: You’re making me think of this book American Amnesia, by [Jacob] Hacker and [Paul] Pierson. If you think of previous crisis moments like World War I, the Depression, and World War II, there was government investment in creativity and innovation to solve some big problems of humankind. But this history has been purposely forgotten. It’s been erased. That’s part of the narrative power of neoliberalism: Silicon Valley and venture capital are the only sources of innovation and are superior to government, when in fact they’re all subsidized by the government to begin with.

JH: If these alternative narratives were more dominant in society today, what could result from that?

DW: It would mean in ten or fifteen or twenty years, we’re actually fighting over more leisure time. It takes me back to the old labor movement demand from the 19th century for the eight-hour day: eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what you will. Bread and roses. I’d love to be having a fight in twenty years: we have these damn three-day work weeks but every other week we actually need a two-day work week! That’s a fight I want to be having!

My partner is from New Zealand, so I’m obsessed with New Zealand. In the last budget Jacinda Ardern enacted, she introduced alternative measures to GDP that were measures of well-being. The index included domestic violence rates, child well-being, and mental health. That might be the fight we’d be having. No one would ever talk about GDP ever again; we’d be having debates about well-being and why we’re not meeting our well-being measures for the society.

JB: How do you see narrative change interacting with policy campaigns or organizing campaigns?

DW: I think it’s an empirical question. I have a hypothesis that having enough narrative power to advance social justice is necessary but not sufficient, and you can’t achieve real change without organizing power, electoral power, and governing power as well. When these elements come together at a particular time and place, that’s when we see breakthroughs.

Until recently, everyone thought Universal Basic Income was a crazy idea. At the Economic Security Project, we knew we couldn’t win the debate on narrative terms alone, so we decided to do some pilots. Let’s go to Stockton, California; let’s go to Mississippi; let’s give people money like a UBI; let’s see what they do with it; and then let them tell their own story about the experience — in their own voices. This was a different way into both the narrative fight and the policy fight, because now Stockton’s Mayor [Michael] Tubbs can go around the country saying: this is the policy I enacted, and this is how it’s worked out. And then, in the last two months, all of a sudden in Washington, D.C., members of Congress are talking about some version of guaranteed income for the first time in a generation. You need all of those different kinds of power moving in some way.

Or take the Fight for $15. It was a crazy idea in 2012. We couldn’t even get President Obama to say he supported ten dollars an hour, much less fifteen. Every progressive economist said it was absurd. So what did SEIU do? They went to Seattle and New York, and did these disruptive strikes, and they organized and got mayors and then governors to enact it. Then they could show the sky doesn’t fall when you raise the minimum wage to $15/hour.

Part of the theory of the case was creating narrative climate change. How do you change the narrative climate so you can get oxygen to the idea? They were riffing off Occupy because it started the year after Occupy Wall Street: there was a disruptive moment that allowed other ideas to come to the fore, and SEIU kind of rode that wave and said, “Okay, there’s some momentum here, let’s campaign and see what it looks like.” The strong narrative frame seemed crazy in the beginning, but with some disruptive action, some organizing and governing power, they were able to enact it.

JH: Does building narrative power require us on the left to develop a more unified narrative that crosses all the different fights we’re having?

DW: (laughs) I think the older I get, the less radical I get, so the way I would reframe it is, it’s a hypothesis to be tested. I think there are several elements that would likely be part of a unified narrative. One has to be reclaiming the concept of freedom. It’s our concept. It’s an emancipatory notion. It comes from the left, and modern neoliberalism stole it from us. It wasn’t a civil rights movement; it was the Black freedom movement. It was “freedom now, freedom everywhere.” There are some other pieces of a puzzle that make up an alternate worldview for me, including the idea of the social surplus.

JH: So, it seems like we need to test the hypothesis whether we need a unified narrative. How might we come up with those crucial elements? How would we deploy it?

DW: My hypothesis is, it can’t flow above ordinary people who are engaged in some kind of action. It has to be actionable; people have to actually do the storytelling in motion, in some way, and I think the best way is a fight or a campaign. I think our mechanisms for making our narratives dominant are different than the right’s because we have different resources. I can’t buy a news station to advance a narrative.

JB: We have a huge advantage because our narrative celebrates what the majority of people actually want and need. So maybe one of the crucial roles of our campaigns is showing people that they can actually get something they want, rather than convincing them it’s a good idea in the first place.

DW: Yes. How do we raise people’s expectations that they deserve the thing they want, and that they can win it. So, it’s about raising expectations and modeling winning as well.

We have all these untapped resources. I’ve been thinking a lot about the role of religion, and particularly the role of the Black church, because historically some elements of the Black church have been movement centers. From a narrative perspective, in any religion — Christianity or Judaism or Islam — there is incredible raw narrative material, which is a huge resource. There’s the David and Goliath story: it’s narrative gold, and we leave it on the table! People already know the story, they could tell you the story, it resonates with them, and they go to church every Sunday: it’s like political education every single week! And we on the left are so secular that we leave all this narrative gold sitting there when we could bring millions of people along if we told some different stories that already resonate with people and their experience.

JH: And it’s crazy how the right wing has taken advantage of that and twisted many of those stories for their own purposes.

DW: I’m from Chicago and when I was a teenager, I started hanging out at Rainbow PUSH Coalition Headquarters. Reverend Jesse Jackson would have this thing called Saturday Morning Forum, and all these people would come through. I would just go and sit by myself and he would have these movement luminaries come speak. If you’re in town, you came to Reverend Jackson’s Saturday Morning Forum. It was like Saturday political church. During the 1995-96 welfare reform fight with Newt Gingrich and Bill Clinton, either Rev. Jackson Jr. or Sr. told a story about how Mary and Joseph were having unprotected sex outside of marriage, and she got pregnant. And it was the most radical thing I’d ever heard. It totally changed my whole worldview. Alright, so they had unprotected sex, they weren’t married, she got pregnant and had a baby, and his name is Jesus. And Newt Gingrich is saying they don’t deserve support? That little example of storytelling was paradigm-shifting. And it was funny but serious, with all the elements of the best storytelling I’ve ever seen.

JH: I’d like to bring us back to the interplay between a policy campaign and the goal of narrative change. Could you imagine Community Change and other groups throwing down on a cross-movement campaign for ideological or narrative change?

DW: I think it’s the next step after the Race-Class Narrative. So yes, I could imagine participating. I think the enlistment would be not a one- or two-year project to win the election but a ten-year organizing narrative campaign that will transform the country. I think we all need help to become more aligned.

JH: Can you think of campaigns or targets that might bring various parts of the movement together and also have a narrative change component?

DW: One campaign in this moment would be against Big Pharma. We’re going to be talking about vaccines for the next two years. There’s already an opioid crisis that few of us have done a good job organizing around. Talking about access to pharmaceuticals has all the elements of monopoly power and corporate power, and it’s a matter of life and death. If I wanted to write a children’s book tonight, I’d write it all about Big Pharma. Easy villain! I would look to the ‘80s and what ACT UP did to take on the drug companies then.

JH: If narrative change is a goal, does organizing need to change its practices, and if so, how?

DW: Clearly, narrative strategy has become more central in the organizing world in the last decade. Previously, it had been dismissed by old-school Alinsky types. We had this period where we said we’re throwing out ideology, because we’re just going to organize people on the issues. That was a strategic mistake. I think now we’re over that hump, and we’re having a pretty vibrant conversation about narrative change.

If I was a new organizer and I looked out at the landscape, I would find it overwhelming. There is so much narrative work and so many workshops and institutes and so on. One of the challenges is to figure out how to integrate a critique of the dominant narrative in our organizing, and advance our alternative narrative of freedom and justice. That is the challenge, and, boy, we have the biggest opening and opportunity of a lifetime to do that, right now. We didn’t plan on it, but here we are! How do we leapfrog over incremental, linear thinking and get to a radically different place around incorporating narrative strategies into our organizing strategies?

JH: What else would you like to say about narrative?

DW: Narrative is a form of power. My favorite book to assign in class was John Gaventa’s Power and Powerlessness. I think it’s the single best piece of social science of the last forty years. I’ve always understood ideology and narrative as a fundamental form of power that the community organizing field abandoned because they got traumatized by strategic and personality conflicts fifty years ago. So, it’s critical that we think of it as a fundamental form and source of power that has to be integrated in everything else we do, and seen alongside other dimensions of power.