In 2015, the Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell v. Hodges that the Constitution guarantees the right to marry for same-sex couples. For Evan Wolfson, this victory was the end of a long road that began 32 years earlier with his law school thesis and that became the driving force of the organization he founded and led: Freedom to Marry. Evan developed a three-pronged strategy to win marriage equality for gays and lesbians: build majority support for marriage equality; win the freedom to marry in a critical mass of states; and end federal discrimination. From the beginning, a core tactic of the campaign was changing hearts and minds.

And they did. Public support for gay marriage grew from 27 percent in the mid-1990s to 63 percent in 2015, when the Supreme Court ruled. In this interview, which has been edited and condensed, Evan walked us through the narrative work it took to win over a majority of Americans and make possible the legislative and court victories for same-sex marriage.

Jonathan Heller: I’d love to hear the story behind your work at Freedom to Marry, the fight for marriage equality, and the role narrative change played in it.

Evan Wolfson: After losing and losing and losing, we began winning and winning and winning. We probably had about a hundred or so court cases on marriage over the decades. Of all of those cases, my favorite passage came in the case in which we won the freedom to marry in Utah, a ruby-red state, very conservative, very religious. In late 2013, we succeeded in winning the freedom to marry there, and the judge wrote in his decision: “It’s not the Constitution that has changed, but the knowledge of what it means to be gay or lesbian.” That sentence captured the essence of the strategy by which we achieved this transformation.

I was not the first person to think of gay people getting married. In the early 1970s, in the immediate aftermath of Stonewall, couples sought the freedom to marry in a wave of cases. One of those cases went to the United States Supreme Court. All those courts, including the Supreme Court, said no; the judges rubber-stamped the discrimination and dismissed the cases. I came along about a decade later. In 1983, I wrote my law school thesis on why we should not take no for an answer and then spent the next 32 years building and leading a campaign that would create a climate in which we could win. The arguments those couples made in the Supreme Court and the other courts in the 1970s, and the arguments I made in my law school thesis were the same arguments that won in 2015. We didn’t need new arguments. We didn’t need to find new rights. We needed to transform the hearts and minds of the public — non-gay people in particular, but also gay people — to want to fight for this. We needed to change people’s understanding of what was at stake and why marriage matters, a project that required and also engineered what one might call a narrative change.

When we laid out a strategy, the strategy that ultimately won, we proposed working on three tracks simultaneously in order to create the climate in which litigation could succeed. The end vehicle was always going to be litigation, but litigation had failed in the 70s, so the strategic question was how do we get the court to do right what it had done wrong? And the answer was that, alongside litigation and political engagement and organizing, we needed to change hearts and minds. One of our three tracks was to build majority support for marriage equality, and then, once we had attained a majority, grow that majority through the power of stories, conversation, empathy, and narrative.

Judith Barish: What were the other two tracks?

EW: Narrative and message are important, but they’re only tactics, elements to advance a strategy; they’re not the strategy. You can achieve narrative change not only through the classic communications toolkit of message, message delivery, messenger, and so on, but also through real-world achievements, from organizing, political work, and court cases. Those victories also shape narrative. Anyway, one track of the strategy was to build a critical mass of public support. A second additional track was to build a critical mass of states in which we have the freedom to marry. And the final track was to tackle and end the federal discrimination that had been overlaid on top of the state discrimination. The idea was that working on all three of these tracks in synergy would change the climate and allow the right litigation at the right time to reach the Supreme Court again — and win.

JH: Give us some examples of the stories that you told to build support.

EW: There were several different kinds of stories we encouraged people to bring forward and then sought to amplify. One was the reality and diversity of gay people’s lives — the idea that gay people were not just whatever stereotypes people had, but gay people are part of families, form couples, raise children, care for aging parents, get sick, break up, have medical problems, have needs, are together for thirty years or forty years or fifty years, and celebrate golden anniversaries. That was one category: all those diverse stories humanizing gay people in the language of marriage and the vocabulary of love, family, commitment, and inclusion.

Other stories were important as well. It was important to hear from non-gay validators. We enlisted family members, friends, and coworkers to talk about the couples, their families, and their dreams. We shared stories of parents who wanted to dance at their kids’ weddings, children who wanted to be sure their families were intact and respected, and even children from heterosexual families who wanted their schoolmates’ families to be honored and respected — like Malia and Sasha Obama, for example, in the story the president told when he explained his change of heart.

There was a category of stories we called journey stories: people who used to be opposed to gay people getting married but then learned more and had a change of heart. We wanted to create space for people to be uncomfortable and then listen and change their minds. Another category of story came from surprising messengers: the 70-year old grandparents, the conservative Republican veteran, people of faith, rural families, and so on. We worked very hard to encourage people to make the case for the freedom to marry in ways that would resonate with the audiences they could reach and the audiences we needed.

JH: I thought you were going to talk also about “love is love.” Was that part of the original strategy, or did it come late in the game?

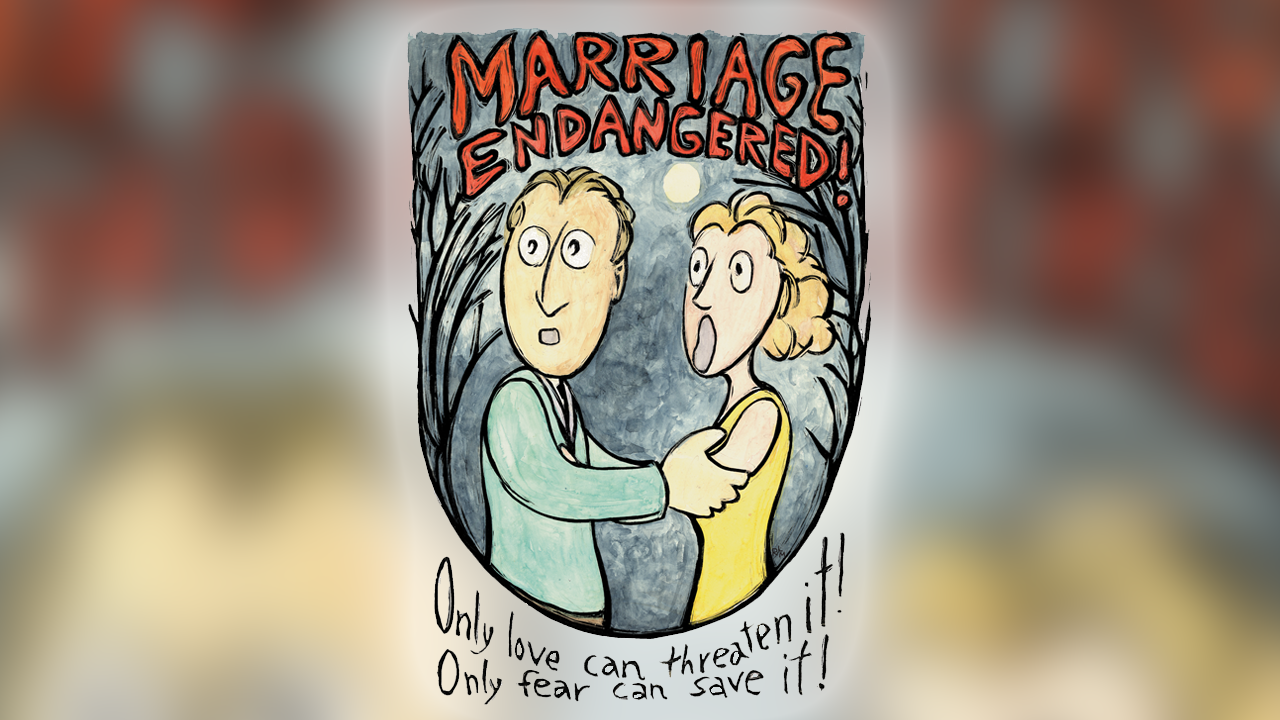

EW: One of the parts of the campaign that is celebrated was our success in recalibrating the overarching message when we needed to. It often gets told as, “They were trying one message — rights and benefits — and it didn’t work, so they changed it to ‘love is love,’ or ‘love and commitment,’ or ‘love and family,’ and then magic happened, and they won!” That’s not the right way to understand what we did and what worked. In 1996, when we won the freedom to marry in Hawaii (later overturned), 27 percent of the American public supported the idea of gay people marrying. From 1996 to 2010 or so, we grew support from 27 percent to about 53 percent — with a mix of authentic messages.

We won majority support. But that majority was fragile; it wasn’t strong enough to win ballot measures. So even though we had slight majority support in California, we lost Prop. 8 in 2008. Even though we had slight majority support in Maine in 2009, we lost. Our opponents were able to peel away enough support to defeat us. So having attained the majority, we knew we needed to solidify that majority and reach not just the people we’d already reached but the next five to ten percent of the American people. Freedom to Marry led an effort to crack the code on what it would take to get the people who were reachable but not yet reached. By around 2010, you could call them the civil union people — they were not so anti-gay that they opposed everything but were not yet ready to support marriage. They thought we should have health care and we should be treated okay, but why did we need marriage? We found, through research and analysis combined with sifting through years of our own experience and anecdotal evidence, that those people would not be convinced by a case that was mixed, which talked about love and commitment but also talked about health coverage or the Constitution. What they needed to hear was the empathy case, the values case, the “love is love” case. So we worked very hard to get our own team, our partners, the media, and politicians to shift to emphasizing that particular authentic message, the one this next swath of potential supporters needed to hear. That was the famous shift from benefits to love. And that shift did indeed build public support from about 53% in 2010 to 63% by 2015, not because what we had done before didn’t work, but because it wasn’t what the next people needed to hear.

JB: You make it sound so intentional and strategic. Do you feel like there were false starts or wrong directions that you learned from as well?

EW: Some of us believed the key to winning was to do the heavy lifting on gay and marriage from the beginning: that we should talk about marriage and about who gay people are. Others believed that was too hard and you might be able to avoid a defeat if you talk about fairness but don’t talk about gay! Or, if you talk about gay, don’t talk about marriage! Or, if you talk about marriage, don’t talk about children! We had these arguments and fights all the time, and many of the campaigns in the ballot measure battles of the 2000s amounted to missed opportunities. Even people who might have suspected we were right wanted to see the evidence, but, because we didn’t have enough polling data or we didn’t have enough money to hire experts or because we hadn’t yet run that campaign, we couldn’t prove that was the right campaign.

In California, several of us believed the key to winning was to solidify a majority before the question went on the ballot or won in court. During the period of 2004 to 2008, we tried to win in the California legislature and succeeded in passing marriage bills, only to be vetoed twice by Governor Schwarzenegger. We realized we were going to have to go to court, but we knew that there was a very good chance we might lose, so we needed to do everything we could to maximize our chances of winning. We also knew that, even if we won, the issue could be put on the ballot as an initiative. Because of this possibility, we pushed very hard to get our California colleagues and funders to fund what we were calling a “soft sell” marriage education campaign. The idea was to grow public support, so we could use that support later in the legislature, with the governor, with the court, and, eventually, defensively, should we come under attack. We set a goal of raising ten million dollars for a pioneering campaign we called “Let California Ring,” to tell the stories of same-sex couples. But it proved to be extremely difficult to raise money when we didn’t have an immediate vote coming up in the legislature or a pending court case. We were only able to run the Let California Ring proactive campaign in two test counties: Monterey and Santa Barbara. We produced a television ad called the Garden Wedding ad, and we did a whole set of print ads that were fantastic. They showed non-gay family members with the gay couple right next to them, and the non-gay family member is the one talking to the audience, and the language is all on script. Then along came the court case: The California Supreme Court ruled in June 2008 that barring same sex couples from marrying violated the state’s constitution. And then we had to fight Prop. 8, an initiative on the California ballot in November 2008 declaring that only a marriage between a man and a woman is valid. The challenge was to run a defense campaign in the biggest state with all the stakes in the world, and everybody knew how important it was, and beyond everybody’s wildest imagination, we succeeded in raising over forty million dollars. But 28 million came in the last few weeks, too late to succeed. The movement and the funders and others showed themselves capable of doing the funding, but only under the gun, and it was too late. Prop. 8 passed.

JB: So what happened in the two counties where you ran your “soft sell” campaign?

EW: So that’s the punchline. The only county in Southern California where voters rejected Prop. 8 was Santa Barbara County.

JH: That’s amazing. Do you have more to say about narrative change, the stories, and the messages?

EW: People love to talk about narrative and messaging. But there are two key points. First, as I said, narrative and message are not strategy; they are tactics. They ought to serve a strategy, which in turn needs to be dependent on the goal. So the right way to do this work is what I call the Ladder of Clarity: Number one, be clear about your goal; number two, be clear about your strategy; and then, number three, look at the vehicles, including messaging, public education, etcetera. These should serve the goal. Number four on the rungs of the Ladder is to be clear about the action steps that can contribute to the strategy, i.e., have a conversation, tell your story, donate, volunteer in a particular legislative or ballot-measure campaign, etcetera.

The second key point is that when you talk about messaging, which obviously is a key way of achieving narrative change, messaging consists of more than just a message. The message is important, but so is message delivery, which includes the messengers, the targeting, the frequency, the venues, the modes, and the vectors by which you deliver your message.

JB: I know you’ve heard the critique that a campaign for the freedom to marry, like the campaign to let gays serve in the military, is in some ways conservative — it’s about admitting excluded groups into flawed, socially conservative institutions and not part and parcel of a larger structural change. How do you respond to that?

EW: I’m used to being criticized from both directions. For years, I was told the campaign was too ambitious, too transformational, too difficult, too unrealistic, and then, at the same time, there’s always been a thread of criticism that marriage equality is too conservative, too assimilationist, too reifying of existing structures, and so on. There is a book called This Is An Uprising by Paul and Mark Engler, and they talk about two models of change: transformational change and transactional change. They hold up the freedom to marry as an example of transformational change because advocates set a goal that seemed unattainable, out of reach —and figured out how to get there — as opposed to setting a goal according to what was immediately attainable and simply going for that. So these scholars see freedom to marry as transformational change, as do I.

We all agree that winning marriage was not the only thing that the LGBT movement wants, let alone the only thing that a progressive wants, let alone the only thing that America wants. No one thing is everything, and winning marriage, however big and bold and transformative as I may think it is, was never the only thing that our movement should be working for or caring about. But I found it easy to choose marriage as a worthwhile goal to organize work around because I saw marriage as both a goal and a strategy. Most gay people want to get married, and, because being denied marriage is being denied something very important, in both tangible and intangible ways, it was worth fighting for. Furthermore, being denied marriage because you are gay is acquiescing to the idea that the government should be able to exclude people from something important simply because of their sexual orientation, so whether or not you actually want to be married, you should have the choice. For all those reasons, I saw marriage as a worthwhile goal. Winning marriage would win us more legal and economic and moral and intangible gains than any other single thing.

But that was not the only reason I chose it. I also believed we should fight for marriage because I believed the work of fighting for marriage, even before we had won it, would be transformational. By winning marriage, I believed, we would be claiming a language of love, commitment, family, inclusion, dignity, and freedom, which was the non-gay people’s language, and, by claiming their vocabulary and their language, we would be seizing an engine of transformation that would change how non-gay people understood who gay and trans people are. And once we had changed their understanding of who we are, we could win marriage, but we would also advance in all sorts of other ways.

I believed this campaign wouldn’t win everything, but it would change everything. For most of those 32 years of fighting, that was one person’s opinion, and it hadn’t been tested. But now, I think the evidence is clear: We won marriage, something people thought was impossible, but at the same time and perhaps more importantly, we transformed the place of gay and trans people in this country. We changed the number of people who support and are open to gay and trans inclusion. We brought more allies to our side than through any other work. We won more nondiscrimination laws, more protections for gay youth, for gay seniors, and for trans people. Our victory in this month’s Supreme Court case, winning employment discrimination for gay and trans workers, alongside others, under Title VII of the federal Civil Rights Act, was yet another example of how the momentum from the marriage conversation and win is the gift that keeps on giving, as long as you harness it to other goals and do the work.

In my view, activism is most successful when it follows what I referred to earlier as the Ladder of Clarity. You work down this ladder starting with where you want to go: clarity of goal, clarity of strategy, clarity of vehicles, clarity of actions. In order to organize your work, you always have to have a goal. You have to be able to say what winning is, and you have to be able to communicate it to others. So, if your goal is the perfect world, then yes, I agree with that goal, but it’s not a sufficiently concrete and clear and mobilizing goal to enable you to develop a strategy and inspire others to join you over the long haul. So you have to choose goals, and they have to be concrete, and they will not be everything. If you reject every single goal because it’s not every other goal, you will achieve nothing.

JB: Does your accomplishment in marriage equality feel irreversible to you?

EW: Well, history tells us that nothing is irreversible. Having said that, I don’t really worry about marriage being taken away, nor do I really worry about the marriage-related gains of the LGBT movement more generally going away, and the reason is because we didn’t win marriage equality through the gift of a president or through the gift of a Supreme Court: it was the culmination of the work we did to win hearts and minds, build allies, and recruit in business, labor, faith communities, among different generational cohorts, and across the broad majority of the public. We now have majority support for freedom to marry in 44 out of the 50 states. I’m more concerned about attacks on trans people, efforts to use religious exemptions to subvert some of the gains we made, and attacks on immigrants, people of color, and women. And, more than all of those, I’m concerned about the country itself: democracy, the rule of law, pluralism, getting our country back on track.

JH: It feels like we’re in a big moment of change. What possibilities do you see right now in terms of changing structures and ideology? And what are the narrative shifts that have to happen to get us there?

EW: I think this is a moment when we can reclaim government and collective action as tools to put a check on power and wealth. We have a tremendous opportunity to do that, using the pandemic to make the case for why government matters, why we can fix things, why solidarity matters, and why safety nets matter. We have a historic opportunity matching the scale of the historic calamity of the pandemic and the historic calamity of Trump. Just as we accomplished the New Deal out of the experience of the Great Depression. We have to take advantage of that opportunity — it won’t happen by itself — but I absolutely believe it’s within our reach.

JH: Should our narrative focus on the role of government? What are the stories that we’d tell communities that have been harmed by government for centuries?

EW: I think they’ve been harmed by the failure of government to serve the full “we, the people.” We have to empower people and transform the government to be what it’s supposed to be. It’s important to hold up the ideals that our country claims to believe in and talk about where we’ve succeeded and the need to do better. We have to force the nation to live up to its ideals. We also need to use the other tools we talked about: empathy, connection, justice, and so on, rather than making people feel like everything is rotten and the only solution is burning everything down. I think that’s a recipe for failure. The success story comes through the use of U.S. values and the periods of success as Archimedean points for leveraging further change. I think many of the people who are protesting for racial equity and justice, and other important, urgent causes, believe in the promise of our country, even though they are very aware of the failure. It’s not that they’re rejecting the promise: They’re denouncing the failure, and rightly so. We should find a positive way to engage that and not foster cynicism and exclusion.

JH: So it’s a narrative of transforming government, pointing to the government we want, and then investing in that government, unlike what we’ve been doing for the last forty years.

EW: We need to return to both the idea and the reality that government is our instrument: It’s the tool of us. It’s not a thing out there that is governing us; it’s us governing ourselves collectively, and having a contract with each other. Government is the instrument of our collective will and collective aspirations, and where it’s been distorted or abused or co-opted by oligarchic forces or racist forces, that’s a failure, not an iron-bound necessity.

I think a message or a vision that is grounded in hope, aspiration, and values that people can connect with is more effective than just fear and certainly more effective than cynicism or denunciation.