The uprisings in the wake of George Floyd’s murder have put a spotlight on police brutality and the racism that enables it. Policing is one part of a criminal legal system that is deeply inequitable, in which Black and brown people are treated unjustly at every step. The legal system has always been deeply intertwined with capitalism, and today’s neoliberal, financialized capitalism is no different. Dominant narratives that prop up neoliberalism — including racist and xenophobic tropes and “pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps” reasoning to explain success and failure — also justify the inequities of the criminal court system. And the logic of the court system relies on its own set of narratives about the forces of law and order, superpredators, and welfare queens.

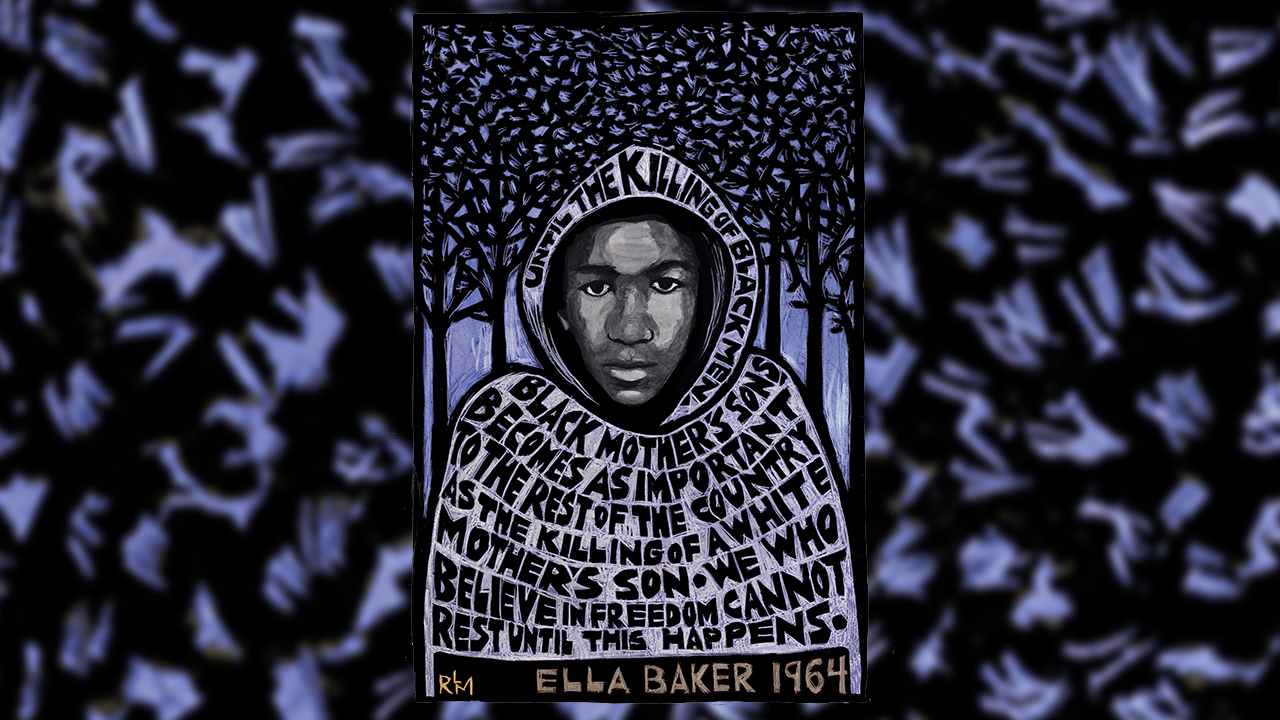

We sat down with Zach Norris, the Executive Director of the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, to talk about his organization’s work fighting the injustices of the criminal court system and undermining the toxic and racist narratives that underpin it. Zach told us about Bay Area experiments that demonstrate that a different approach to community safety is possible and shared his organization’s recent success in closing the remaining youth prisons in California. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Jonathan Heller: How do you see neoliberal, financialized capitalism as being related to the inequities of the criminal justice system?

Zach Norris: Neoliberal capitalism is a root cause of the injustice we’re facing inside of the criminal court system. But before getting to the modern system of capitalism, we have to look at the origins of capitalism in the United States. We need to acknowledge that the foundation of capital is the stolen land and stolen labor of indigenous and Black people.

The attempt to rid the nation of indigenous people can only be described as genocide. Its vestiges are reservations inside the U.S. Indigenous people are still fighting for their sovereignty: The Navajo Nation has the highest rates of COVID infection, and yet they had trouble erecting simple health checkpoints to test people for the virus as they moved into the Nation.

Prisons are also a vestige of slavery and injustice. Prisons began after emancipation when plantation owners were trying to get Black people back onto the fields and not pay for their labor. That brought about the Black Codes. Land owners were saying, “You’re vagrant. You don’t have a job. We’re going to arrest you and force you to work on this plantation.” That history still lives with us. As Bryan Stevenson says, “slavery didn’t end; it evolved.”

We see the same high rates of morbidity and mortality inside prisons today that we saw under the plantation Black Codes system. What we see now in terms of neoliberalism and financialized capitalism is just the acceleration of the dehumanization of certain groups of people and putting profits before all else. When Trump was elected, the stocks for private prisons jumped immediately because people knew he would detain more immigrants. They did not think about whether that is a good or bad thing; they were just trying to make money. The bets made as part of financialized capital also resulted in the housing recession, in systemic harm that we’re not really addressing.

Financialized capital has a huge role to play in the problems of the criminal court system. That system hides the harms resulting from inequality, like housing shortages and the housing recession. It points attention to the streets and the corners, rather than to the suites and the corner offices where people are causing great harm, but not being held accountable. It’s part of a larger system of casino capitalism that has hurt all of us, not just Black and brown people and indigenous communities.

JH: Would you name some narratives associated with our neoliberal society that are harmful to the folks you work with?

ZN: I only have to say two words: welfare queen. Instantly an image and a story will pop in your mind, the story of a Black woman defrauding the government. That was the story intentionally told by the most powerful folks in this country, including President Reagan, to undercut support for welfare programs that benefit both communities of color and white folks. As a result of that story, we saw a bottoming out of people’s wellbeing across race.

That narrative was coupled with criminalization. It was designed to say that Black mothers are deserving not of support from the government but of being criminalized. I remember a story of a Black mother who had a job interview in Phoenix but didn’t have childcare. She brought her kids and left them in the car. That was clearly not the best thing to do; it was hot. Thankfully the kids were fine, but she was arrested, and those kids probably ended up in the foster care system. Rather than looking at the great lengths she was going to support her family, it was seen as an opportunity to criminalize this Black mother.

We’ve had success in fighting that narrative, but it has been an uphill battle. The media, the communications power, and the bully pulpit that Reagan and the corporate forces behind him had have been really pervasive.

JH: The world’s been turned upside down in the last few months, with the pandemic and the uprisings over George Floyd’s killing. Do you see this as an opportunity to make significant change in terms of those stories that you’re talking about?

ZN: Naomi Klein has talked about how crises present opportunities. The amount of change that we’re going to be able to make in this moment of crisis depends on how prepared we are for it. We have been preparing.

The mythology about youth superpredators has resulted in billions of dollars being spent for youth incarceration across the country, hundreds of millions here in California. For over a decade, we’ve fought a campaign to close youth prisons here. We’ve organized families and young people and, over time, were able to change the minds of legislators. Those legislators had that mythology in mind when they met with families of color. We described the lengths to which families were going to visit their children and grandchildren, the treatment youth got in those prisons, and just how desperately young people and their families wanted to succeed. And the legislators started to change their minds about youth prisons. Through a combination of challenging structural racism and economic arguments, we ultimately got legislators to restrict the number of young people who could be sent to youth prisons. Over time, we helped close five of eight youth prisons across California.

Now, as a result of COVID and this economic crisis, there’s not enough money coming into the state. Legislators are having to make budget cuts. The governor just announced he is closing the last three youth prisons and two adult prisons as well. That would not have happened without all the organizing that preceded it. It’s a welcome development, and, if done right, it would be a huge first step.

We could now take some of those resources and invest in community-based programs that have been operating on a shoestring budget but have had tremendous success in reducing violence in communities. We could be investing in the work of Pastor Mike McBride and the work of DeVone Boggan at the Richmond Office of Neighborhood Safety, public health-centered violence prevention programs that have proven track records in reducing homicides. That would keep communities safe and build prosperity in communities that have been marginalized by neoliberal capitalism and a punishment economy.

Judith Barish: Power structures are resistant to change. One of the things that upset me about the George Floyd story is that the same thing happened in Minneapolis five years ago.

ZN: It’s absolutely infuriating and indicative of how systemic this is. The media portrayals tend to focus on an individual story in ways that aren’t helpful for understanding the long history behind police violence, even the way the police were created. We need to give folks more of a history and a root causes analysis.

We have to do that same level of preparation that created this neoliberal order. The Powell Memo laid out for the right the need to organize the Chamber of Commerce, take back the narrative, lift up corporations, and diminish the role of government. They had a strategic plan in terms of the narrative and how they wanted to get their message out. We have to think in that same long-term fashion.

JH: I hear you saying that one of our strategies should be to provide people with a history and an analysis around existing dominant narratives. Is another part of the strategy to push a different set of narratives?

ZN: Yes. One of the narratives we try to put forward is that public health issues should be addressed with public health solutions. Rather than criminalizing students for school discipline issues, we could provide school counselors. Rather than criminalizing drug use, we could provide people with the drug treatment they need to lead successful lives. That is a narrative we should be spreading far and wide.

The premise of the book I wrote, called We Keep Us Safe: Building Secure, Just and Inclusive Communities, is that we can’t take care of public safety if we don’t take care of the public. We need to understand that we are interdependent. This COVID-19 pandemic shows that our health is connected to one another. This should be an opportunity to think about public safety differently. Not focusing on a limited set of crimes that are out in the open, but thinking about the systemic harms that are pervasive.

In the book, I tell the story of Anita De Asis. She grew up in Southern California and went to University of California, Santa Barbara in the late ’80s. At the time, fees in the UC system were beginning to skyrocket. In the span of 18 months, she was raped at a fraternity and her mother died. She was fighting the fee hikes but also dealing with this trauma. She did not complete school and ended up homeless with her daughter. All those harms were underplayed or disregarded by the criminal court system. Interpersonal harms, which disproportionately impact women and gender non-conforming folks, aren’t addressed by our criminal court system. Institutional harms — economic harms like homelessness and fee hikes for a student who can’t afford them — aren’t addressed by our criminal court system.

We have an opportunity to push for accountability in a way that is broader and more systemic.

JH: Is narrative change a goal of the campaigns you run?

ZN: We’ve done a better job challenging existing narratives than developing our own new narratives. We’ve talked about Books Not Bars, and Jobs Not Jails, and Health Care and Housing Not Handcuffs, but, frankly, we’ve been stronger on the “Not Handcuffs,” the “Not Bars,” and the “Not Jails” than on the vision of what we want.

We’re just starting to promote our vision of what safety looks like with positive examples, promising storytelling, and brick and mortar. If I ask you to think of a time when you felt safe, you might think of a time when you were with family or at a house of worship or surrounded by the people who care about you. We know that safety is intimately tied to relationships (which prisons sever).

We have a new initiative called Restore Oakland, through which we are creating a visible, tangible example of what community safety looks like. It houses restorative justice, economic opportunity, and community building. It is oriented towards holding elected officials and other powerful individuals accountable. Those are key parts of safety.

JH: Do you have thoughts about how a narrative of abundance or one focused on the social surplus could be useful in your work?

ZN: One of the key impediments to bringing together folks on the left is creating a shared narrative. A narrative of abundance and interdependence is hugely important. We often talk about the amount of resources spent on incarceration and what it would look like to free those resources to support communities.

Neoliberal capitalists believe that government spending is bad unless it’s spending to protect property and inequality: investment in military, prisons, and policing. Even with the HEROES Act, they snuck in additional funding for riot police in the context of COVID relief.

That is a central part of what we have to overcome. We need to explain that we have the means to survive —and that we have an abundance. I think there is a possibility of affirming life by asking government to play a positive role. Instead of enforcing an unjust state of affairs where all of us are struggling and starving and many of us are dying, the role of government should be to affirm life and ensure all of us have enough to thrive.

JH: The right’s narrative elevates the economy above all else. People serve the economy. We could lift up narratives that center people and the dignity of life.

ZN: We need to find ways to affirm life and the need to care for one another. One of the challenges with any narrative that just focuses on economics or race or any particular area is that we have a combination of systems of hierarchy that interrelate and aggravate each other. We have a human hierarchy connected to race, class, and gender. Caring for one another has been so diminished in our patriarchal society. This idea that we should all be tough, never cry or show emotion, and not care for one another is deeply embedded in our culture. At the same time that we’re affirming life we have to challenge patriarchy. Let’s use the social surplus to care for one another.

JH: Does racism interfere with advancing the social surplus narrative?

ZN: Yes. You can’t have a social surplus that belongs to all of us if there is no “us.” The criminal court system has been designed to reinforce long-standing narratives that label people of color as undeserving and place them outside the beloved community — outside the scope of human concern. We have to combine this narrative of possibility and abundance with notions of interdependence. We need people to see we have a shared stake in lifting the prospects for communities that have been marginalized and disenfranchised.

JH: How can organizers change narrative?

ZN: There has to be an organizing cadre thinking long-term. We need support for long-term campaigns, with ten-to-fifteen years of funding, to test out different things over time, see what works, and be able to experiment and iterate. It would be helpful to have more collaboration and discussion with other community-based organizations. We could come together and make commitments in terms of time and budgets to win the long game.

JH: Do you have any other thoughts you’d like to share?

ZN: One of the stories in my book is about Richmond, California. At the turn of the century, Richmond had one of the highest per capita murder rates of any city in the country. The city declared a state of emergency and was up in arms about what to do. DeVone Boggan put forward the idea of creating a mentorship program for Richmond’s young men. The city didn’t know what he was talking about because they only thought of those youth as being responsible for 70% of the homicides. Partly because they had tried everything else, they decided to invest in DeVone’s program and created a fellowship program. The young men got a monthly stipend, travel opportunities, and mentorship from formerly incarcerated folks. Over a five year period, this project helped reduce the crime rate in Richmond by 70%.

This was significant not just for these young men but for Richmond as a whole. Grandmothers could take their kids to the local park. Shopkeepers could keep their businesses open longer. If we invest the social surplus in a particular way, we all reap the benefits of people doing well.

These are the kinds of stories we need to tell.

This is what it means to support folks and provide the resources many of us take for granted. People understand safe neighborhoods aren’t safe because there’s a ton of police; they’re safe because people have good jobs and access to opportunity and believe they have a future ahead of them. That’s true not just in the context of your own situation, but across race and across communities.