Listen to the interview here.

This interview, which has been edited and condensed, was taped before the Supreme Court’s recent DACA decision.

Solana Rice: We are so excited to have Greisa Martinez with us from United We Dream. United We Dream is the largest immigrant youth-led community in the country. They create welcoming spaces for young people, regardless of immigration status, to support, engage, and empower them to make their voice heard — and to win. Let’s start things off by getting to know you, Greisa. What has brought you to the fight for racial and economic justice?

Greisa Martinez Rosas: I’m undocumented, unafraid, queer, and unashamed. And it’s an honor to join you all. I started this fight ten years ago. My family and I came to the U.S. when I was eight years old. We crossed the Rio Grande waters, and we all grew up undocumented in Dallas, Texas. When I was just starting off in high school, I heard about this law that had passed here in Washington, D.C., that would say that my dad and my mom would be considered felons just because they were undocumented — and they could be put into jail. And the very thought of my mom and my dad, the people that I looked up to, being able to be targeted in that way just made my blood boil in a way that it had never done before and it connected a lot of moments for me.

My dad used to collect these wooden pallets, he would take pleasure in going around the factories collecting them out of the big trash bins, repairing them, the broken ones, and selling them back to the factories to be able to make money to pay for rent. My family and I had this tradition on the weekends [of] going with him. We were blasting music. We were all in it, and it was my job to go and scout the bin and see, like, oh, what’s in there. And if there was a good haul, then I would send a signal and everybody came. And one of those times, my dad and I encountered a white man who was, you know, guarding the space, and he saw us and he just started yelling really racist things. He was calling us “wetbacks.” He was shaming my mom and my dad for having their kids out there with them, accusing my parents of being thieves. And how he looked at us, the hate and the racism that I could feel in my skin and the shame and confusion that I saw in my mom and my dad’s eyes. It was something that I never forgot, and then when I saw this law come into place, it just connected that moment about — it’s not just happening in the factory spaces. It’s happening nationwide and I needed to do something about it. So, I organized my high school to have these walkouts in 2006, and we started a movement that led to mega marches of millions of people across the country, demanding justice for immigrants. And from that moment, seeing that young people could lead the way, could set the tempo for what the rest of the country will look like, I got hooked. Since then, I’ve been organizing with undocumented young people on behalf of workers, women, queer people, and people of color in the U.S. And that’s what brings me to this site.

Jeremie Greer: This edition of The Forge is on racial capitalism and connecting many elements of the progressive movement to racial capitalism. So we’ve been asking everyone this question: When you hear that term, racial capitalism, what does that mean to you?

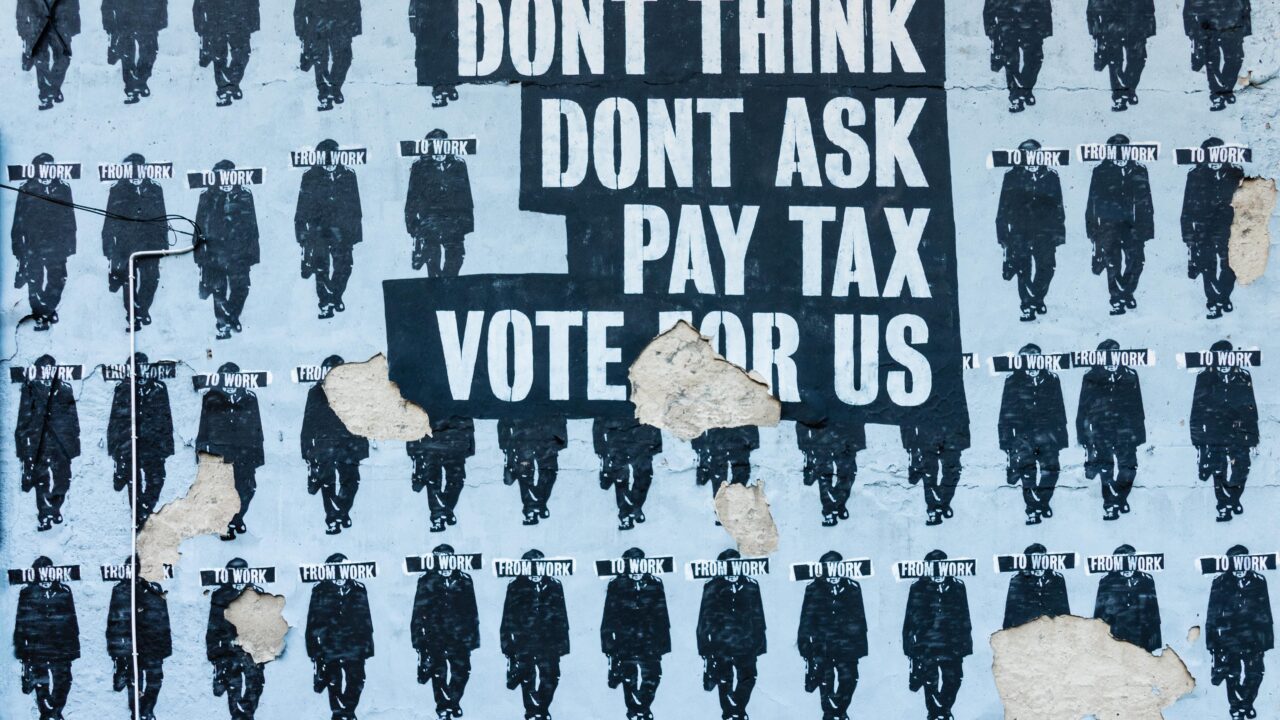

GMR: You know, at United We Dream, we have this thing we call real talk. So, real talk, to be honest with you, racial capitalism is a new term for me. I learned about it just a couple of years ago. I know that it’s brought to us by Cedric Robinson, I know that it’s also grounded from a South African tradition. For me, it’s really about the understanding that capitalism requires racism, they cannot exist without the other. When I first learned about it, I thought about what I learned in Texas schools about racism and that it required white plantation owners to see a racial difference between them and the slaves on the fields to ensure that they were extracting profit, extracting benefit from a racial category. At that moment when I learned that, I thought about my own history. One of my grandfathers was a bracero in the U.S., and he would come to the U.S. to farm, to pick the produce. He would tell stories about being sprayed with all these pesticides, so they would feel safe, the white people and the white growers. I think that it’s a relationship that unfortunately has led me into a realization that I’m really honored and really humbled to be able to keep learning about it. That we can’t undo racism without undoing capitalism. I think that for us at United We Dream, we are mostly a youth-led organization. This isn’t something that they teach you at school. And this isn’t something that you have a test about. And so it has been one of our goals to ensure that people are really able to understand it, but it’s not like this big term that should only exist within the context of universities and college courses. It’s something that every one of us experiences. We all have stories that we can connect to in our relationship of racial capitalism, and I’m excited to figure out how to best put into that context, the fight for immigrant rights.

JG: In United We Dream, you are really on the front lines of organizing around reforming the immigration system, the U.S. immigration system. I wonder if you could talk about how racial capitalism affected the design of our immigration system as it exists today.

GMR: One of the things that we talk about when we think about how immigration systems have been designed: All of it has been really grounded on our labor, on the labor of immigrants, being able to be cheap, available, and disposable to corporations and to rich people. And so I think that there’s been, through my time, there’s been a lot of conversations around compromise. If you want the 11 million people to have citizenship and to be able to have a workplace here, then you also should have enforcement agents and ICE and CBP. And for the last 40 years, we have seen that every negotiation has had that framework that, in order to get protection, you have to give something on enforcement. And every, every time, we’ve had zero citizens and the budget for ICE and CBP has grown from zero to now more than $22 billion every year. If that is not an economic influx for racism and enforcement on people of color, I don’t know what is. And the role that United We Dream has played in ensuring that we are very clear about what we want is that, we reject the framework, the political framework that says that in order for you to have protection you need to give in. It’s false. It hasn’t worked for us. And it also has led to the mass deportation of millions of people, detention of our folks in concentration camps across the country, and it has led to the death and murder of immigrants and people of color in the U.S. We understand that they just want our labor. They want our food. They want our music. They want to be able to bear witness to our joy. But they don’t want to recognize our dignity and give us the respect that we deserve. And so our job is to ensure that we are not convincing people of our humanity, but rather building the organizing infrastructure, the independent political power, and the cultural interventions to get what we deserve.

SR: I think that’s so right on. Stop convincing people of our humanity. According to reports, there are 3.6 million immigrant youth. These are immigrants that have entered the U.S. before their 18th birthday. Many have lived their entire lives in the U.S., but they are undocumented immigrants. At United We Dream, it sounds like you’ve focused intensely on advocating for this population of immigrants. Can you talk about the unique challenges that face immigrant youth and the advocacy that you’re building with them?

GMR: I will say, at the start of it, and I’m not sure how folks can relate to this, but as a child of immigrants and people of color, you do everything to help make your parents proud, or at least get them off your back. And so, at United We Dream, our fight really started with the desire to go to college, for some of us to be able to say: Hey, my parents sacrificed all this, I’m supposed to go to college and now you won’t let me do that. And I share that story because it really wasn’t out of self-interest, it was out of a family commitment. A commitment that, this is my contribution to the work. And I do this on behalf of my family: my mom, my dad, my loved ones around me. And the reality is that undocumented young people were portrayed by folks as this ideal immigrant with the cap and gown, that would be more tenable to the conversation in the U.S. And we have used that as a strategy to be able to advance the conversation — and for this country to know our families and you know our community. To support an undocumented immigrant youth with a cap and gown has been to also support our moms and dads and the people that made us. We call them the original Dreamers.

Our work is to organize young people because we believe that they have always been at the forefront of creating the cutting-edge strategy. We believe that people at the center of the pain are also at the center of the solutions, the innovations and the breakthroughs and that part of the opportunity of organizing young, undocumented people or people that are part of an undocumented family, is the fact that we can navigate the systems of the US in a different way than our families can. Being able to take advantage of all of the opportunities that we have at our disposal to advance the shared agenda that all of us — all 11 million of us, all undocumented people in the U.S. — deserve dignity and respect. Part of what we’ve done is be able to drive interventions. When we first won the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) protection from deportation, it was coming from a demand of: Stop deporting us. Quickly after we won that, we went back and demanded the same protection for the rest of the undocumented community, and we won. That was intercepted by Republicans but that’s been our ethos. We start off with a larger picture, we pick campaigns that are tenable, winnable, and build movement, but we don’t stop just at undocumented young people. We have a larger vision for our community.

SR: You mentioned the strategy. I’m curious about how your advocacy has been affected under the Trump administration?

GMR: You know, the Obama administration unfortunately was responsible for the largest number of deportations that this country has seen: Three million deportations in the U.S. When Donald Trump took the Presidency, I think that we braced for the worst. And unfortunately, that has come to pass. We have seen the uncovering, like this country is bearing witness to what it means to be a person of color in the U.S. and that immigration systems and enforcement are just one of many ways — we call it the three headed monster of police, ICE, and CBP that are coming into our communities. And they are even more empowered to conduct raids, to rape our women and people in detention to — we have a story of Claudia, a young indigenous woman who was traveling into the U.S. and was killed pointblank by a CBP agent and left [on] the side of the road until they were able to come for her.

It is not a new phenomenon that Donald Trump is exposing, but it is a new intensity. And with it comes a lot of opportunities to be able to expose the pain, to be able to talk about the billions of taxpayer dollars that are poured into these unaccountable enforcement agencies, and the connections between the local police that are killing Black men and women on the streets are also enabling the detention, deportation, and death of immigrants in the U.S. There is a confluence of Black immigrants, Black Afro-Latinos that are at the conjecture of all of these different systems and that are bearing the brunt of [them]. To be a Black immigrant in the U.S. is to be at the mercy of whatever the police, ICE, or CBP would have you to do.

But it has also offered us shared opportunities. In the last couple of years, United We Dream, inspired by the movement for Black lives and the framework that folks have carried for generations on an invest-divest framework, we have adopted it and called for an abolishment of ICE. We have been able to move the conversation forward and launch a campaign, the Defund Hate campaign, that in the last three years has stopped $11 million from going into ICE and CBP. The moment that we’re living in is an example that we can’t stop there and that we must be able to demand exactly what we deserve.

JG: Greisa, I love so much that you made that connection because it really segues into something I wanted to talk to you about. You mentioned your grandfather being a bracero and the use of immigrant labor to turn our economic systems. And when I have listened to the debates over the years, I hear echoes — and, you know, I’m Black — and I hear echoes of the same kind of rhetoric from Democratic and Republican politicians when talking about immigrants, as you heard when they talked about Black people coming into Reconstruction during Jim Crow and the dehumanization, almost speaking of Black people as not even citizens that deserve the full rights and citizenship that is provided when you live in the United States. Am I right in making these connections and are there particular basic government rights that are being withheld from immigrant communities that we should all really focus in on?

GMR: There’s definitely a connection. There’s obviously differences as well. To be Black in America is a completely different experience, and we understand that there’s also a lot of work to do within undocumented Latino and immigrant communities to undo anti-Blackness in our work. So I wanted to start off with, like, they are similar but they are not the same. When it comes to politicians, we know that the growth of enforcement around immigrants, the growth of mass incarceration for Black people, was brought to us by a Democratic president and the Democratic Congress. That does not escape us. It also does not escape us to know that the last fight for permanent protection for immigrant young people, where we were close to passing it in the Senate, was stopped by five Democratic votes that decided not to vote with us. This is not a partisan conversation, but rather one around human dignity and the lack of political will on both sides to enact change.

I’ll say that, through all of these different fights and all of the battle scars that we have gathered in the last, I would say 10 to 15 years of the immigrant youth movement, we have also asked ourselves a couple of things. One, what does it mean to demand or have our goal of citizenship if Trayvon Martin was a citizen and was killed in the streets? What is the goal of having citizenship, if people that are U.S. citizens from our mixed-status families see, feel and experience the same kind of poverty, the same kind of exclusion from opportunities and the same kind of mental health threats? We see citizenship as one step to bring equity into the conversation and to get us into a different playing ground — and yet we do not see it as the ultimate goal. The ultimate goal is to ensure that we are bringing dignity, access to the things that we need for all of us. And that also includes, you know, the people that might disagree with us. And so I think that our vision has to be able to be broader than that. But one of the things that we have learned is that particularly in this moment that we are seeing the deaths of Brianna, and all of the people across the country, there is a question about: Personally, for me, why do I want to belong to a country so much that doesn’t want to belong to me? Why do I fight to… all of our work is about belonging. It’s about being part of a community, being seen. And part of being seen is about having access to vaccinations, being able to have access to clean water. And, you know, in the last couple of weeks, I asked myself: Why did we come here? And I’m so grateful for organizing because it’s part of my faith in action, that it has reminded me that it is not about what is, but it’s about what can be. It is about what organizing can construct. And if this country is not the country that my parents and my grandparents thought that it would be, we found it not to be the promise, we found the American dream to be false. Then it is incumbent upon me to ensure that this country is what they wanted it to be. It is what they wanted, what they deserve it to be. And so part of my commitment and the commitment of United We Dream is to not give up, to create our own spaces of belonging within our own organization and our own community spaces. And to push and demand for this country the dreams and the promises that were made to our ancestors and ensure that the generations that will come after us have a better playing ground, to ensure that their lives are better than the ones that we had to live, unfortunately.

SR: What, from your perspective, can advocates from other areas of the progressive movement do to support the immigrant rights movement?

GMR: I would say there are three things. The first thing is to really understand that in order for any one of us to thrive, Black folks have to thrive. And ensuring that our work is grounded in undoing anti-Blackness because anti-Blackness also equates anti-immigrant sentiment that sometimes shows up, actually frequently shows up, within progressive spaces. So, centering Black lives and centering Black liberation is important. In order for you to help immigrants, you have to be able to do that work.

The second thing I will say is, we all have the responsibility of creating an ecosystem that truly embodies what we believe at United We Dream: that those directly impacted closest to the pain — because they are closer to the solutions, the innovations, and the breakthroughs — should be in decision-making places and places of power. It is undeniable that the reason why we’re in this moment where this country has leaped generations in our understanding about policing and calling for defunding the police is because Black people have led us to this moment. That is the same when we think about all issue areas. When we think about a Green New Deal, when we think about undoing ICE and CBP, when we think about bringing health to our communities. The people most directly impacted should be in the place of power to make decisions on how we move forward, not because it’s like a fluffy value thing, it’s a checkbox, but because — and Rashad Robinson says this a lot, it is strategic. It is strategy. If you want to win, you have to do that.

And the third thing I will say is, as a daughter of a Southern Baptist preacher, though I have my qualms about organized religion, the ability to hold onto hope and to joy is as important as having a clear political analysis that really understands what racial capitalism is because the fight is long. I have a teacher that talks about this long arc — and the long arc extends seven generations behind us and seven generations in front of us. And the ability to hope and to dream and to have joy for the generations that are to come, are going to be important for us to be able to make it through. So, you know, I’ve been thinking about this moment, and I can’t help but go back to some of the stories that I grew up [with]. I think about the story of Exodus and how the people had finally broken through, they had broken out of Egypt. They were probably dancing, eating some good food, and they knew that there was no way that they could go back. There was no way that they would go back to the lie that they were powerless, the lie that they were unworthy, the lie that their bodies were only useful for labor for someone else’s benefit. And they also saw these huge oceans in front of them that they had never navigated before — and it feels like that’s where we are. And it will take courage to take this new leap, a new kind of courage that I feel is within us, but we must understand it as a new kind of courage, of building something new, of demanding exactly what we deserve. And not allowing for Pharaoh’s army, the ones that are taking over Washington D.C., that are putting people into jail across the country. We must not allow them to take us back into a time where we were in the shadows of our closet or the shadows of our status or the shadows of who we really are. Those are the three things that are in my brain about how people can stand in solidarity with immigrants and how together we can all get free.

SR: I hear that preacher coming out in you. That’s fantastic. You talked about keeping hope. What’s giving you hope, what’s giving you life right now?

GMR: That’s a really great question. My sisters are giving me hope in life. You know, there are four of us. I’m the oldest, there are two of us that are undocumented, we have DACA. Both our parents were taken from us either by deportation or by death because of lack of access to health care. And the fact that my sisters and I are still committed to this promise of the vision that our parents had for our lives and the fact that we still can get together on Sundays and be our most fancy selves and drink mimosas and make my mom’s chilaquiles, that stuff brings me joy. And the work that I do at United We Dream grounds me and why I’m doing this and building up the house for the next generation of people to come.

SR: I am not a churchgoer but amen, and Greisa Martinez Rosas, you are giving me hope today. Thank you for joining us. We so appreciate you taking this time and sharing your words and your insights. Thanks so much.

GMR: Thank you.