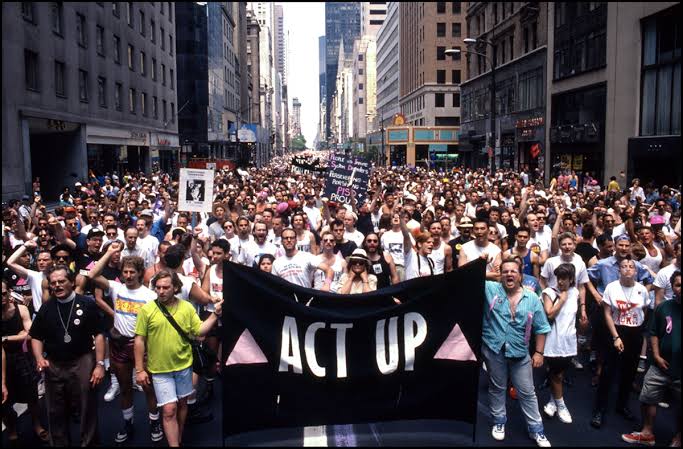

ACT UP was the most dynamic organization on the left in the US in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Hundreds of people came to meetings on a regular basis, and thousands took part in big actions. They were united by a principle of unity — direct action to end the AIDS crisis — a common purpose that allowed for affinity groups to organize actions independently. The affinity groups were the core of ACT UP, enabling the organization to scale, provide care for members, and employ a range of tactics.

ACT UP is a critical organization to examine when looking at the history of rupture in the United States. ACT UP members took huge risks in the face of great desperation. They blocked streets, disrupted Catholic mass, took over the news, and mobilized thousands of people from across the country to shut down the Food and Drug Administration. ACT UP changed the narrative: people with AIDS were not passive victims; they were fighting in the streets for better treatments, access to healthcare and housing, needle exchange programs, and more. They challenged the homophobia, racism, and misogyny that underlay the government’s inaction around AIDS, forcing those in power to respond to the crisis. Through an effective inside/outside strategy, the group won on many of its demands, including expedited drug approvals processes and access to experimental treatments for all people with AIDS.

I sat down with Sarah Schulman, a member of ACT UP New York who has spent the last couple of decades documenting the history of the group through an oral history project, a documentary film, and, most recently, the book Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993. There are all kinds of lessons for organizers in the interview, but three stand out. First, Schulman argues that the 1986 Bowers v. Hardwick decision upholding the constitutionality of state sodomy laws helped to catalyze the formation of ACT UP — giving me some hope for more direct action around reproductive rights in a post-Dobbs world. Second, Schulman pushes back on the need for consensus. Members shouldn’t “have to agree in order for projects to go forward,” she argues, as long as there’s a “bottom line” that every action has to meet. The goal is action and scale, not process.

Finally, Schulman characterizes ACT UP a vanguard organization, but I think most organizers today would be thrilled if hundreds of people regularly showed up at our meetings and over one thousand engaged in significant direct actions. This is the clear challenge: how can our organizations truly become mass organizations or even vanguard organizations capable of the level of sustained disruption that ACT UP was? Is creating rupture a critical piece of the puzzle in helping us to build and maintain mass movements in the United States?

This interview has been edited and condensed.

How did things go from the initial call to action to creating ACT UP?

Well, as far as I know, Larry [Kramer] ran around and got people to come to the meeting and that’s how these things usually go. If you just call the meeting and say, “What do you want to do?” — that’s not good leadership, right? To ask specific people to come, to tell them what your goals are, and to set it up beforehand is the best way to go. And [Larry] went to people who had already been in some previous organizations. The Lavender Hill Mob was a direct action group. This group called The Network, which was before GMHC (Gay Men’s Health Crisis), people like Eric Sawyer — so he got people in the room. And then, the Silence=Death project, they were there, so there was some previous organizing. And then [Larry] gave his speech and people in the room said that they wanted to meet again. So they picked a day a few days later, and they met again and then they met again at the NYU Law School. And then they met again at the Center and that’s how they got started. One of the things that’s interesting is that the meeting was held in the Gay Community Center, so they held the meeting in a place that people already went to, right? A lot of people, when I interviewed them, said, “I was hanging out at the Center or I went to this other event at the Center and then I saw all these people on the first floor and I wondered what they were doing.” So picking a space that the community already uses and already trusts and identifies with is a really good idea from the top.

Were meetings led by consensus?

No. ACT UP was never a consensus-based movement. It never went by consensus. It went by Robert’s Rules of Order and majority, and that’s one of the reasons it was successful. I think that’s one of the big takeaways from ACT UP: if you wanted to do something and I didn’t want to do it, we would argue, but basically if you met the principal of unity, which was one line — direct action to end the AIDS crisis — that was the whole principle of unity. There was nothing else. If you met that, basically you could do it, but people didn’t have to all do it and there was a lot of yelling and screaming. It was pre-gentrification New York culture, and people were dying. It was very tense. And we actually are still yelling and screaming at each other in our 60s and 70s, so that has continued.

Let me give you a more concrete example. Needle exchange was a controversial thing because, at the time, the prevalent theory was abstinence for drug use. Harm reduction was a brand new idea and was considered a radical idea. The Black community in New York did not support needle exchange and there were a lot of people in ACT UP who did not support needle exchange because they didn’t understand the concept of harm reduction. So when active and former drug users came in and said, “We want to exchange needles,” there were people at ACT UP who did not support that concept. So they would argue. But in the end, if you didn’t like it, you just wouldn’t do it. You wouldn’t stop other people from doing their idea. So the people who wanted to do it, they would go do it. If you wanted to do something else, you would get your five people and you would go do that.

This is actually what made ACT UP very successful because there was a simultaneity of response. And there were so many different kinds of campaigns and projects going on with different kinds of people, using different aesthetics and different strategic and tactical approaches — all at the same time. This is really what created the paradigm shift. Movements that try to force everybody into one analysis or one strategy, I think they have all failed. Because people can only be where they’re at.

Real leadership is something that helps people be effective where they’re at instead of trying to push people to be different than who they really are because that doesn’t work. That’s hard for people to accept. One of the biggest problems with the left is that — something that hasn’t worked in the past, you would think we would not try it again. But the left consistently repeats failed strategies and failed tactics, over and over again. And this is one of them: trying to force people into consensus. So there was no consensus. But what’s also interesting is that ACT UP never decided not to have consensus. It just evolved organically and it was never debated because ACT UP did not theorize itself. It had no theoretical discussion whatsoever. Everything was driven by people with AIDS and their needs. People with AIDS were considered to be the experts and they needed treatments.

You probably already know this, but AIDS is an umbrella term. It’s like cancer; it’s different in each person. People’s immune systems would break down and they would get these opportunistic infections, and they needed treatments for each infection. Pharma didn’t want to do that because it’s a smaller market share, right? So they needed to push pharma to create treatments for each of these little infections. That’s why ACT UP had to be effective because the clock was ticking. So there was no debate of any theoretical anything. And there was never like, “Should we be a consensus-based movement or should we do this?” None of that was ever discussed.

Theory emerged through the process of action. So you would decide a concrete action. And then, as you made decisions about how to do your action, that’s how your theory would emerge because you have to find out what your values are to decide how to do your action. But if you do it the other way around — with theory first – you’ll never get anything done because you get polarized and there’s no application. But that wasn’t decided theoretically either, that just happened because people needed things because they were sick. The clock was ticking and that’s what organized the structure of the group.

Were the early actions affinity group based?

Affinity groups happen for a bunch of reasons. One, ACT UP was a very social organization because people wanted to meet friends and lovers, and it was very cruisy. But there also was this other reason, which is that people were worried that the group was infiltrated by the police. And actually, when I did my book, if you look at the back, I reproduced the Freedom of Information Act files, and it was completely infiltrated. At the time, I thought it was an overstatement and it was paranoid, but actually it was more infiltrated than we realized. So having this parallel structure was quite wise.

So there was an official structure, which was a Monday night meeting that would be 300 to 700 people. There were official committees. Anyone could be on a committee and each committee had a representative on the Coordinating Committee. They would meet separately and they would decide things like how to do what the floor wanted. But then there was this underground structure of these affinity groups that would be 10-to-15 people. They would meet privately in people’s homes, and they would plan a lot of illegal actions, which would never be approved by the floor because the floor was infiltrated. But there was so much trust in the organization that affinity groups had full legal support from the organization, even though we didn’t know what they were doing. So they would have legal observers, and when they were arrested, they would be represented for free by the ACT UP lawyers. Lori Cohen was just one of many lawyers, and she personally did 10,000 cases — and these were all pro bono. Everybody worked for free, everybody. And then these affinity groups sometimes became care groups when people got sick. And some people are still very close friends with people who were in their affinity groups.

So the affinity groups were longer lasting structures. They weren’t —

Some of them. Sometimes you’d have an affinity group that only did action. But if you look at our film, United in Anger, you could see that when there’s a big action, like at the Food and Drug Administration or something like that, there’s little groups of people who have all planned different actions. They look different and they’re doing different things — those are affinity groups. They plan their own thing. And then when there’s a big event, they would all come in and nobody would know what each other was going to do.

That model is still used in many spaces today for all the reasons you’re talking about — for security culture, for not getting in the way, they trust affinity groups will take a piece of turf if you’re trying to blockade something. I think what’s less common is their being longer-term places for care — that’s why I was curious about the longevity both as a way to care for each other and build affinity.

Well, I think a lot of people were quite sick and this was a factor through the whole of ACT UP. Many people died in ACT UP.

How did you build in the space for grief?

It wasn’t. I mean, it was a very ongoing experience. People were constantly dying and people were very sick. How old are you?

52.

So did you know people who died of AIDS?

Absolutely.

Okay. So you know, it’s a horrible, horrible death and people really, really suffered.

Yes.

And so, you were watching people go blind. I mean, it was terrible. There was no system for grief. I mean, we had memorial services, but sometimes there were many in a week. And it was interesting, when I interviewed people…. We started the interviews in 2001, and they went for 18 years. Let’s say ACT UP broke up around ’93. The first people we interviewed, that’s eight years after. And then the last people we interviewed, that’s 26 years after. That’s a big difference. But many people we interviewed had never talked about what happened. A lot of ACT UP people had a lot of problems with meth and still do. Serious drug problems, and also seroconverting very late in life. People who stayed negative all through that period, then at age 55, they would seroconvert. That was common in ACT UP. So things expressed in their own ways. And there’s still quite a few people who died of drugs and people still have drug problems. So if you read [the ACT UP Oral History Project interview with] this guy, César Carrasco, he became a psychiatric social worker. He works with long-term survivors from that very first generation. He talks very wisely about the myth of resilience and what happened to that generation and how lonely that is and how much they’ve suffered and how little they’ve been addressed. So I would say, it was unaddressed.

Yeah. It’s harder for me to sort out just because, for me, it was both coming out and then losing mentors. And then talking to the generation slightly before mine, where folks would tell me about doing care work in the early and mid 1980s.

Well, that’s interesting. Okay, so let me just give you the timeline. So AIDS is recognized in ’81, right? And ACT UP starts in ’87, because Bowers v. Hardwick is ’86. And that’s very interesting to look at with the Supreme Court — the Dobbs decision — because Bowers upholding the sodomy law in the middle of the mass death experience. That’s what politicized gay people and that’s why ACT UP comes just a few months later. But in the first part [of the 1980s], all the gay community did was try to create social services because familial homophobia was a very big factor. People did not have any family support.

So that’s when you get GMHC, which starts the buddy system. There was a group called Paws that would walk people’s dogs. There was God’s Love, We Deliver – it was trying to create a facsimile of family. So that was the first thing the gay community did. The political response took six years.

I want to come back to mass actions. So you have the first mass action on Wall Street.

The issue was lowering the price of drugs. And this comes back now, we’re dealing with the same problem now: private sector pharma gets all this government money, our taxes. They develop these drugs, then they make a fortune. And then, internationally, poor countries can’t even get the drugs. And here in some cases, people can’t… And with COVID, total replay. I mean, nothing has changed, zippo. And that’s what the first demonstrations were about. It’s interesting because if you look at the arc of the politics within ACT UP, the earlier people were more left. Vito Russo and Marty Robinson, they died of AIDS, but they were old lefties and they had always been out and they wanted universal healthcare. They were targeting pharma. They were targeting corporations.

Later, a slightly more conservative group of people came in from Harvard, and they were the “drugs into bodies” people. The first group literally died. So it got replaced by a group that was a little bit more conservative but who were more successful working with pharma and working with the government because they were more similar to them. They were very successful in what they did. These were not ex-hippies. These were people who had gone to Harvard. So there are phases of antagonism or cooperation with corporations.

Was that a live debate?

Sometimes. Because this is pre-internet, right?

Right.

So consistency of information is different because the only way you get information is if you go to a room and somebody tells you something. There’s no newsletter or internet or anything, so it’s not that consistent. But if you read my interview with David Barr, he talks about organizing demonstrations so that certain people could get access to the government or to pharma. So that was called the inside/outside strategy.

One of the ways that this broke down was around women because women were completely excluded from experimental drug trials. Because in the ’60s, there was a drug called Thalidomide that had been given to pregnant women and they had gave birth to children born without limbs. They sued for hundreds of millions of dollars. So pharma’s response to that was to say, “No more women in experimental drug trials.” So women with AIDS could not get into trials. And in those days, if there’s no treatment, trials are the only treatment. So that was a corporate issue — that was not a government issue. And if you read my book, you’ll see that some of the men in ACT UP were meeting with corporations and were meeting with Fauci and were not even talking about women.

The women had to fight for two years to get a meeting with Fauci. And then when they had a meeting with him, it blew up because he just didn’t respect them. So there were parallel worlds inside the same organization. And the same thing happened with the drug users. I mean, there’s a story in there where Richard Elovich, who was one of the organizers for needle exchange, he went up to Fauci and he was like, “How come you’re not enrolling any drug users in these trials?” And he was like, “They’re not reliable.” And Richard was like, “No, you cannot write off an entire class of people.”

So this is the same organization. Different castes of people are having different access and then have to use different strategies because you have to use strategies based on your social position. If you were in a social position with no access, you have to use much messier strategies then if you can call somebody you went to Yale with who owns Bristol Myers — like Larry Kramer could do — and get a catered lunch at the pharma, right? You don’t have to break into the office and yell and scream and handcuff yourself to people and do all kinds of messy things. Or literally exchange needles illegally so that you get arrested so that you have a test case, which is high-risk behavior, right?

I want to stay on the question of mass actions. Is there an anatomy of a mass action that you want to break down?

I mean, in my book I have a whole chapter on the FDA action, so we can start with that one.

Okay.

So David Barr and his people wanted more access. They were trying to get meetings with the FDA. They couldn’t get them. A playwright in ACT UP named Jim Eigo, he was in a different group that had been studying the FDA and how it was organized. He designed a solution called “parallel track,” which allowed sick people to get access to drugs that had not been approved. So he sent it to Fauci. Fauci never answered. Then he had to show up at a meeting where Fauci was giving a public speech and scream at him. David had this really smart idea, because at that time, the left would either go to the White House or the Capitol, the White House or the Capitol.

And he’s like, “No, let’s not do a symbolic action. Let’s go to the actual building where the people who are actually hurting us are.” And that was the smart thing that ACT UP did; they did not really do symbolic. They went directly. But David was not a really charismatic guy, so he picked this young guy, Gregg Bordorwitz, who was like the Romeo of ACT UP. He was this bisexual guy; he was very vulnerable and young and cute and everyone was in love with him. Eight people I interviewed were in love with him. David took Gregg out to lunch and he was like, “You’re going to make a great leader,” and dah, dah, dah, dah. He got Gregg to stand up at the floor and propose this action. So there’s all kinds of internal politicking all the time. And I remember when Gregg proposed the action, and I thought it was Gregg’s idea, but whatever.

So then at that point — ACT UP New York had been the first ACT UP. Now there were a few others in the country. So they decided to make this action at the FDA the first national action. They went to California and they met with a few other existing ACT UPs. In the end, there were 148, but at this point there were four. And they were like, “No, no, the Capitol” because the left always repeats strategies that don’t work.” So they basically said, “We’re New York, and we have the most people and we’re going to the FDA in this weird suburb, Rockville, Maryland. So, fuck you.” They pulled the New Yorker thing. And then everybody said, “Okay.” So then all the affinity groups started planning their action at the FDA.

Mike Signorile, who did the media, he had come from People magazine and he had really good media skills. And Anne Northrop came from CBS. And Urvashi Vaid, who just passed away from cancer, was a genius organizer. They came up with a few really smart ideas. So Mike called all the media and told them it was going to be bigger than the action at the Pentagon, which was a major anti-Vietnam war action. This was a total lie, complete lie, but he told everyone. And they were like, “Oh my God, it’s going to be bigger than the action at the Pentagon.” Urvashi came up with this incredible idea of getting people with AIDS from every major city. And so the press came thinking it was going to be bigger than the Pentagon, and he was like, “Person with AIDS from Cincinnati over here.” And then the Cincinnati paper could talk to them. “Person with AIDS from Dallas.” And this way they all had a local story and could get on the front page of every local paper. That was Urvashi’s idea. So they were doing all that brilliant stuff.

Each affinity group planned an action, so there was all kinds of crazy stuff. Peter Staley climbed up on the eaves, overlooking the thing, and people broke the glass on the front door of the thing, and people were lying there with cardboard gravestones, and other people had bloody science jackets. I mean, and the people in the FDA had never seen anything like this, and it was huge in the media. And we won. They did take parallel track, so that was the first national action and it was a big success. David Barr told me that the next day they took his call.

Oh, wow.

We didn’t know the whole thing was to get the government to take David Barr’s call. I didn’t know that, but it was. And they did. So this was the inside/outside strategy and those of us on the outside didn’t really know there was an inside/outside strategy. No one in ACT UP stood up and said, “There is an inside/outside strategy,” but the guys who were inside were thinking that way. And it was for the best, but I think if we had known, it might have been a different ending because these things later surfaced in a negative way. But at that time it was positive.

I want to go back to Bowers v. Hardwick. It’s very salient now. Did folks really think that it was likely that the sodomy statute would get overturned?

I don’t know, but people were very, very angry and there were really angry demonstrations in New York and Washington without permits. This created a politicization because, you have to remember that most people are in the closet when AIDS started, right? So being out in the street as a person with AIDS is a big deal and people had to get really mad to be able to do that. So without Bowers v. Hardwick, there would’ve been no ACT UP.

Yeah, that’s really interesting. Do you think there’s a modern analog for —

Dobbs, what just happened at the court with —

Yeah but not about people being scared to be out in the streets.

Well, see, abortion has been structured as a woman’s personal problem. And women have been hung out to dry. They have to go out and confess that they had an abortion. But the truth is men benefit from abortion, women’s parents benefit, their other children benefit — it really is a collective event, but it hasn’t been presented that way. So that needs to be restructured because right now everyone is on their own. Women are on their own right now. So in that way, you could see a parallel.

Do you also see a parallel with GMHC in that the largest group that is mobilizing around choice is also the nation’s largest service provider?

There’s a lot of history to that. You had two movements: you had the single issue, abortion rights movement and then you had this radical reproductive rights movement that had a large coalition that included sterilization abuse, childcare, which is an issue that has fallen completely off the table. So the grassroots radical reproductive rights movement countered International Planned Parenthood. Planned Parenthood is essentially a corporate reproductive rights movement because it provides healthcare, it provides birth control, it provides all kinds of services. And they became the front line because everything has gone backwards. Abortion rights only existed from ’73 to ’79 — ’79 is the Hyde Amendment. The Hyde Amendment took away Medicaid funding except in seven states. So since ’79, poor women, except in seven states, cannot get abortions in this country anyway. And a lot of states haven’t had any abortion availability. And a lot of the states that are shutting down now, like Louisiana or whatever, they had one abortion provider or two abortion providers. I mean, they barely had abortion, right? And so anyway, what’s just happened [with Dobbs] is of course a cataclysm, but it’s been happening since ’79.

So I wanted to go back to this question about recruitment. Larry Kramer put the initial group of people in a room. Were there other points where folks were actively propositioning or doing one-on-ones to get people to come to things?

No.

And what about when Urvashi’s idea was to get someone from every city who had AIDS. How did that work?

No, they were coming. Her idea was to match them with the media. ACT UP did not have to recruit. But don’t forget, it was not a mass organization; it was a vanguard organization because we never had more than 700 people in the room. Our largest demonstration was only 7,000 people and that was at Stop the Church in December 1989. So it was just that the people who were involved were totally committed to being effective. They were a very small group of people who were incredibly effective.

Organizations that would call themselves mass organizations today would be delighted to have the numbers of a vanguard organization.

Well, then they’re not mass organizations.

Was that a conversation? Did folks say, “We’re a vanguard?”

No, never. There was no theoretical discussion. These people didn’t know what the word vanguard meant. There were a few old lefties, like Maxine Wolfe. I mean, there were some old lefties, but nobody read anything or knew the history of the left. They didn’t even see themselves as part of the left because don’t forget that the left had rejected gay people.

Yep.

The Communist Party had expelled gay people. The Civil Rights Movement had famously sidelined Bayard Rustin. The Women’s Movement had a number of lesbian purges. So the left had rejected gay people at this point.

Oh, that I remember. Yeah, I mean, it’s why I have this aversion to parts of the party left. What are the key lessons or takeaways from ACT UP?

I think the biggest takeaways are internal, radical democracy, where people don’t have to agree in order for projects to go forward, and that you have a bottom line. So that active bottom line was direct action to end the AIDS crisis, that was the statement of unity. And that meant, no social services. That’s what that meant: direct action only. So they couldn’t do any social service. If you do social services, you had to leave ACT UP. So that’s why Housing Works came out of ACT UP — they had to leave, for example. So I think the number one takeaway is radical democracy internally. Let the people in the group do projects that other people don’t like and don’t agree with, as long as it meets your bottom line. The second is no theory.

And the third really important lesson is that — ACT UP was a white gay organization, but there were women and people of color in the organization and they tended to be more politically experienced. But the way that they operated was the opposite of how people operate today. They never would stop the action to say, “You used the wrong word” or “You need to have consciousness raising about racism” — none of that ever, ever, ever. What they did instead was they marshaled the ample resources of the larger group for their own constituencies. So, for example, ACT UP was able to raise a lot of money. And if the Latino Caucus… When they saw that people with AIDS in Puerto Rico had no support, they just went to fundraising and got the money and went to Puerto Rico and started ACT UP Puerto Rico. And that’s a lot smarter than saying, “You’re a racist; let’s do a study group on Puerto Rico.”

Or women with AIDS who tended to be poor, if they needed to go testify at a hearing or something, they needed to travel, they needed a hotel because people were sick, they would just go to fundraising and get the money. I think that’s a very smart way of doing things. Keep your eye on your prize. You have your concrete goal that you’re trying to win. If you’re a minority and a group of people have more access to money than you do, just use their money. I think that’s a really good lesson because you could spend your whole life trying to change one person. And this thing that we’re in now, where people are trying to micro control everybody, it’s so stupid. It’s just not… Who cares? What is your larger goal? What are you trying to accomplish? What is your campaign? What resources do you need to win your goal? That’s what your focus should be.

I think what you’re generally talking about is how it was a radical democracy at every point, where folks had freedom and autonomy to do things, the structures were loose enough that it was a culture of yes — almost, you know, if you need a thing, you make a plan and go do it. Although it’s a question then about who has access. To your point on, you know, Latinx groups being like, “We need money for Puerto Rico.” Oftentimes, they would say, well, it’s white folks or folks with class privilege who have more ability to work the systems of these kinds of organizations and get what they need and figure out the strategy as opposed to folks who are working—

That was not the case. I mean, there was a small group of elite people. First of all, most white men are just the same. I mean, they’re not rich. And that’s an error, that assumption. But there was a small group of elite people. And then there was a small group of people who grew up working class but had developed access to the elite. And those people organized an art auction that raised $650,000 and that money was available to everybody. So the other thing is big tent politics. It’s, you work with people when you agree with them. And when you don’t agree with them, forget about them. Because if you spend your whole life trying to fight with them, then it’s a waste of time.

And now when there’s so many communities that are… everybody’s in trouble right now. The whole world is in trouble. So when you see somebody’s doing an event or a campaign that you agree with, work with them on it. It doesn’t mean you have to work with them on everything. You can work with people that you have profound disagreement with about very profound things, but you don’t have to work with them on everything. It’s like the Catholic Church, there may be a Catholic Church in your community that has a really good position about the police but has a terrible position about abortion. So you don’t work with them on abortion, but you work with them on the abolition issue. You have to be a grown up to do politics that way, but that’s what works.

Yeah, that’s right. As they say, “No permanent friends, no permanent enemies.” How do you think about the power that ACT UP built and wielded?

One of the interesting things in ACT UP is it had no spokespeople and anybody could be a spokesperson. So there were these series of teach-ins — every time we had an action we had teach-ins. So the rank-and-file was extremely knowledgeable. And in my interviews, it was fascinating, every kind of person had very sophisticated knowledge of issues. We produced really informed, sophisticated people and many of them went on to do very interesting things. So in a way, that’s ACT UP’s power. I was part of a group called the Lesbian Avengers that came after ACT UP and we trained a lot of people. Women who had no leadership training. And wherever I go now, I’m 64 almost, I meet people who say, “Hey, I was a Lesbian Avenger in Corvallis, Oregon. I was a Lesbian Avenger in Boston.” And now a lot of them are in leadership positions. So it’s the kind thing that’s very hard to trace exactly what the power is. There were some heavy-duty people who came out of ACT UP.

Were there particular points at which, when you look back, where you said, “Here’s a key strategic decision point where we maybe should have done things differently.”

It’s not that orderly because there’s no “we.” There’s so many different things going on at the same time. I mean, when we started interviewing people, Jim and I realized right away that everyone in ACT UP thought that what they and their friends were doing was ACT UP. So I discovered entire campaigns that I had known nothing about, even though I was in ACT UP, by interviewing people. There was so much going on, it’s phenomenal. I didn’t know that there was a Haitian underground railroad that was getting housing for HIV-positive Haitians who were incarcerated in Guantanamo. That was part of ACT UP’s housing committee. I didn’t even know that existed until I started interviewing people.

I know there was a huge amount of repression in the streets, how folks were denied access to medicine, all this fucked up stuff. Were folks worried about long-term sentences too or was it —

Everything changed when Giuliani became mayor. Then it was very different. But under Dinkins, it was quite lenient. It’s a larger philosophical question because ACT UP operated on “no business as usual.” In order to be effective, you had to give up your ambition of succeeding in the society. So if you are screaming at the New York Times and the government and the art world and science, you’re not going to get a job at the New York Times or the art world or whatever. You have to give that up. And if you’re trying to play it both ways, which is what people do now, you can’t impact the institutions. But people had to give it up because they were going to die. And apparently that’s the only thing that makes people give it up. So that was a very different cultural frame.

Is that an implicit or perhaps explicit critique of organizing in the nonprofit industrial complex now — that folks want to have it both ways?

Well, we were not part of that because ACT UP never had a 501(c)(3).

Oh, I know, that’s why I’m asking.

Well, I mean, I have never been comfortable with those. I mean, our position was that we were a political movement and so we didn’t apply for grants and we are supported by the community. Now, of course, gay men have more discretionary income than any other sector of the country because it’s households of men’s incomes. And anyone who partners with a man benefits financially because of the difference in what women earn and what men earn. So anybody whose constituency is men can raise more money. I came from the women’s movement where you couldn’t raise any money. And suddenly you’re in ACT UP, and I’m at a table selling Silence=Death buttons and people open their Velcro wallets, in the day, and give you $20. I was like, “Wow,” because they had it.

When Jim and I started the experimental film festival mix, which ran for 33 years, our original principle was, if the community likes it, they’ll pay for it. And also at that time, there was no funding for gay things. You couldn’t get… You didn’t think that way because there wasn’t anything because homosexuality was illegal. It’s another world. So I was a journalist in the gay and lesbian press, right? So I was out, but we didn’t get paid. The gay people who worked at the New York Times, they were in the closet. It’s the same thing in academia. If you wanted to be professor, your dissertation or your first book, it couldn’t be on gay things. So that was the dividing line for people. People who wanted to be out, they had to give that up.

And people who were willing to be in the closet in some level, they could access those institutions. And that was a certain kind of person. As Donald Suggs, who was a Black gay leader, who’s dead now, but as he said, “The drag queens who started Stonewall made the world safe for gay Republicans.” And that’s true. And the radicals were the first people who were out because they were so alienated anyway. And then people who were embedded in the institutions, it became safer for them to come out. It’s an irony of history, people who make change are not always the people who benefit from it.