Youth organizing typically takes place outside the walls of the classroom. However, our public education system — the institution impacting more young people on a daily basis than any other in the United States — can play a critical role in ensuring that all young people develop the acumen, knowledge, and desire to become politically engaged. One component of a robust civics education includes fostering skills to collaborate with peers and advocate for policy changes to improve quality of life in a community — in other words, organizing skills.

The experiential educational approach of “action civics” incorporates elements of youth organizing into social studies in a non-partisan, interdisciplinary, and academically rigorous manner. Notably, because action civics is school-based, it can reach a broader audience than organizers alone can and be a vehicle for students to learn concrete skills in democratic engagement.

In 2017, for example, David Edelman and his high school social studies classes at Union Square Academy for Health Sciences discovered that water sources at their school contained elevated lead levels. Some faucets and fountains had well over 1,000 parts per billion of lead, significantly above the 15 parts per billion that is safe for human consumption.

Mr. Edelman had recently joined an action civics program through Generation Citizen, a national civics education organization with which we are affiliated. Despite his passion for social studies learning, Mr. Edelman felt constrained by his standardized curriculum and the overarching need to focus on test scores. He was energized by the opportunity to provide students with concrete tools for political participation and to make fundamental connections between social studies learning in the classroom and opportunities for social change in students’ daily lives.

Mr. Edelman’s social studies students had long known that much of the school’s available water was cloudy. The school’s poor lead testing results drew more attention to this ongoing problem. However, because “lead remediation” in New York City public schools can technically be accomplished by simply turning off the water source, the school was not obligated to provide safe water. Inspired by the activism of young people in Flint, Michigan, Mr. Edelman’s students launched a campaign to expand the availability of safe drinking water at their school and to advocate for a city policy requiring the release of statistics about the lead levels at all schools.

The students began researching how to replace water sources to ensure clean water at school. They educated and organized the broader student body about water quality in their school and community, with 11th and 12th graders conducting outreach to younger peers in 9th and 10th grades. They connected with the student council to get approval to share their findings with peers during lunch. They also conducted outreach presentations in other social studies classrooms, as well as at teacher team meetings. As a next step, they broadened their advocacy by calling local council members’ offices, conducting letter writing campaigns, and meeting with City Council staff to advocate for the policy goals identified above.

Last semester, Mr. Edelman offered students a menu of three choices for an individual advocacy project — running a social media campaign, writing a letter to an elected representative, or recruiting peers for awareness building and organizing for change. Elizabeth Pluma knew immediately that she wanted to pursue peer organizing, which she saw as the best way to push for broader change. Elizabeth developed an outreach campaign targeting her church’s youth ministry, with the goal of encouraging and enabling them to conduct water quality testing at home. After helping church members order water testing kits, she documented their results and reported them back to Mr. Edelman’s class.

Drawing from the class’s own home lead testing and that of Elizabeth’s youth ministry, Mr. Edelman’s class decided to shed light on the role of zip code on water quality. Students gave presentations in other classes to encourage Union Square Academy peers and teachers to test their own home water quality and created a simple Google survey to collect and document all results — including those of the class, the broader school community, and Elizabeth’s youth ministry. Mr. Edelman’s class used the data in a letter writing campaign advocating for improved water safety regulations.

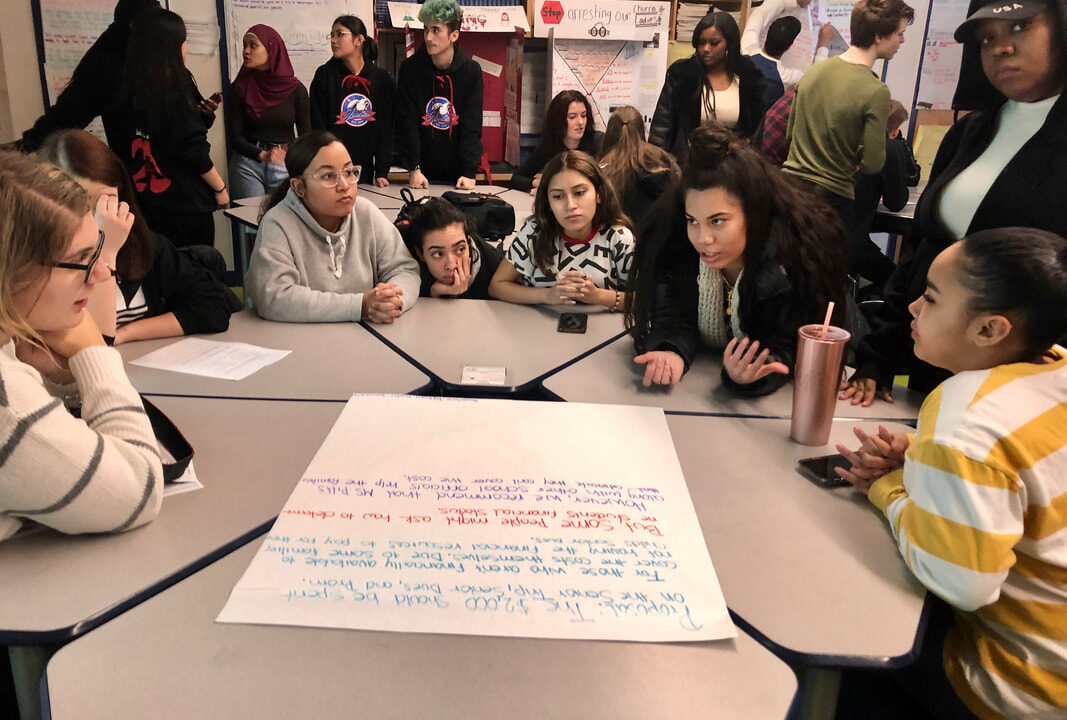

When Mr. Edelman and his students secured $2,000 in funding from the New York City Department of Education through the Civics for All initiative, which supports opportunities for students to develop civic engagement skills, they decided to host a school-based participatory budgeting process in collaboration with the student council. They identified a number of pressing school needs, including the lack of clean, safe water in their building, the need for bathroom and gym upgrades, and a desire to expand school clubs, tutoring, and field trips. The students saw the vote as another avenue to conduct school-wide civic engagement and organize the entire student body around a tangible goal.

Eighty-one percent of students turned out for the vote, exceeding participation in most municipal elections. Mr. Edelman attributes the robust turnout to the fact that the election was a real participatory budgeting activity with a tangible and specific outcome, not a theoretical exercise in civic participation and education. The student body overwhelmingly voted for a proposal to purchase and install two new filtered water fountains in their school, no doubt because of the ongoing advocacy of Mr. Edelman’s students. While the students have yet to secure their citywide policy goal of making public and transparent water safety and availability at all schools, the vote secured a previously unattainable goal for Union Square Academy — clean, filtered water for all students.

That said, in light of our public school system’s bureaucracy and the years students spent struggling to get access to clean water in their building, Mr. Edelman reports that it was initially challenging to convince them that the vote would allow them to access real funding to fix their water access problem. It can be difficult to convince students that organizing and advocacy within a classroom can be effective. That’s why it’s so important to build school and classroom democratic culture — to give students agency and to foster classrooms in which they have a voice. Action civics can play a role in this process. By learning about how to advocate for school and municipal policies that impact their daily lives, students experience democracy on a granular level.

Some youth organizers have questioned whether in-school civics education is an appropriate venue for community organizing. They see civics education as narrowly focused and doubt its ability to spark transformative policy change because it is embedded within our public education system, which itself is a government institution. While it’s true that Mr. Edelman’s students have yet to secure broad citywide policy change, they have developed invaluable advocacy and organizing skills grounded in an understanding of policy making that they are able to continue applying outside the classroom on a larger scale.

To be fair, because action civics is integrated into school curricula and infrastructure, students may find it difficult or even prohibitive to organize or advocate against the school system itself, even when structures may be oppressive. Teachers may get pushback from school administrators if their students select campaigns that challenge their own policies. But ultimately, the specific policy priorities of action civics campaigns — while important, meaningful, and empowering — are less central than the process of teaching students concrete skills to organize and advocate for change. Although Mr. Edelman’s classes have yet to secure the citywide policy changes they seek, they have learned to examine community challenges, conduct peer outreach and education, and craft policy proposals.

Action civics can serve as a powerful bridge between organizing and education. We need all students to develop the skills and inclination to be informed political actors — including those who do not have the access or inclination to get involved in organizing campaigns outside school. Action civics can play a vital role in educating students of all political stripes and backgrounds to be effective civic actors and participants in our democracy.

Although action civics is not tied to any political orientation, it has nonetheless attracted critics who aim to limit young people’s say in the political process. As of the end of July 2021, legislative or regulatory policies to limit or ban the implementation of action civics curricula have been passed or proposed in six states. While these bills vary from state to state, they generally ban or disincentivize schools from implementing action civics curricula and prohibit social studies classrooms from engaging in hands-on practicums or advocacy work. Should they succeed, these laws could cause social studies education to remain static and theoretical, separated from students’ everyday lives — and students could be limited in their opportunity to gain practical hands-on civics skills as part of their secondary education. It is critical that organizers and education advocates work together to defeat these bills and ensure that robust, nonpartisan civics education — including action civics — is implemented across the country.

Action civics empowers young people to apply their learning to address community issues within their sphere of influence and to strategically pick policy goals and strategies that maximize their chances of success. Their work demonstrates precisely how action civics teaches the democratic values of civic participation, debate, and dialogue within the community and advocacy to improve it.