Webinar: Chicago Teachers Strike for the Schools Our Students Deserve and the City Our Community Deserves

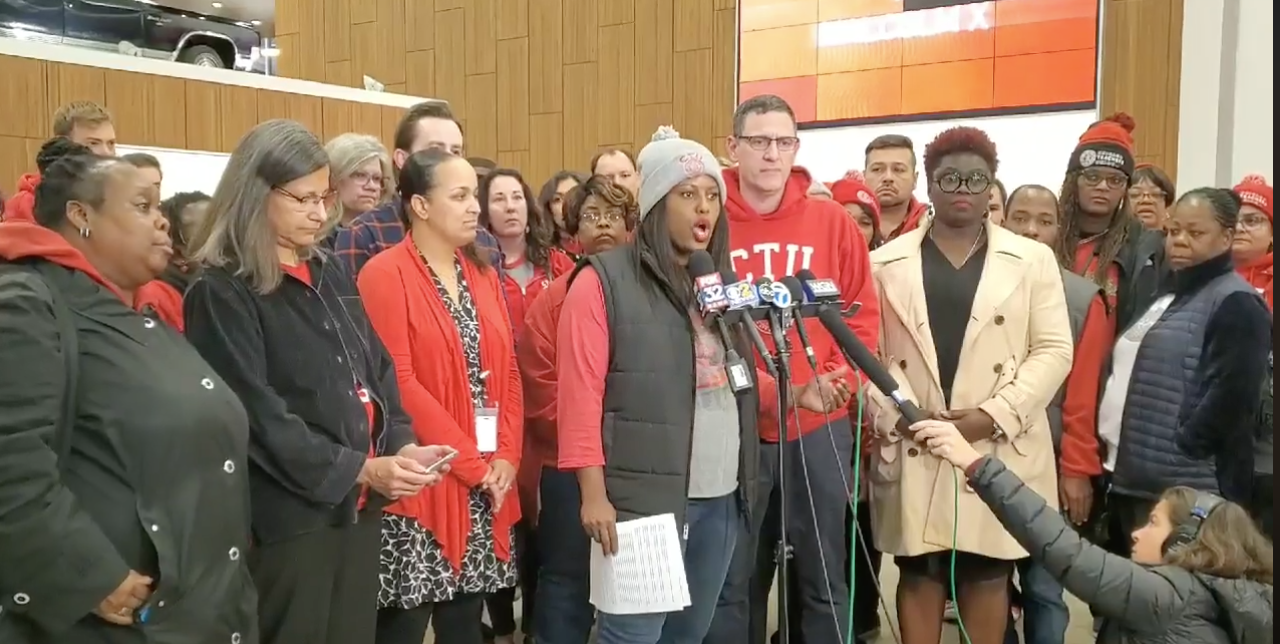

A conversation in March 2020 with Stacy Davis-Gates, Vice President, Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) and Amisha Patel, Executive Director, Grassroots Collaborative about the October 2019 Chicago teachers and support staff common good strike.

Excerpts from the webinar

What is the Bargaining for the Common Good (BCG) approach? Community and union members partnering around a long-term vision for the structural changes they want to see in their communities and using union bargaining as a critical moment in a broader campaign to win that change.

Saqib Bhatti, Co-Director, Action Center on Race and the Economy (ACRE): The very first BCG network conference held in 2014 was inspired by the cutting edge community-labor partnership that won the CTU strike in 2012. They struck to improve the quality of education in Chicago Public Schools and the platform for the strike was “The Schools Chicago Students Deserve.” That campaign fundamentally redefined people’s ideas of the role that unions can play in changing power dynamics in their cities and states. It made people realize that when unions and community organizations come together to fight for common good demands that that gives them transformational power.

BCG campaigns led by network partners are building on CTU’s work and have spanned from California to Massachusetts, Washington state to Puerto Rico.

Leaders at CTU, the Grassroots Collaborative and their partner organizations in Chicago have kept up the pressure over three contract cycles to fundamentally change their city. They have won groundbreaking demands around issues like sanctuary schools, counselors and nurses and art and music education in 2012, 2016 and 2019. They have won hundreds of millions in progessive revenues, helped cancel corporate tax subsidies to some of the most powerful corporations in the state.

What happened in Chicago in 2019 was a decade in the making.

Marilyn Sneiderman, Executive Director, Center for Innovation in Worker Organization (CIWO), Schools of Management and Labor Relations, Rutgers University:

Stacy and Amisha, I thought the best way to start was just to have you both tell us a little about your story. What really happened, both in the strike, but also leading up to it? What this experience has been like for you, what you were working for, what you won.

Amisha Patel (excerpts): Grassroots Collaborative is a community and labor coalition working on economic and racial justice issues. We are in our 20th year. The goal is to try to build the kind of infrastructure we have built in Chicago around the state.

What the teachers were able to win in Chicago is built on a decade of work. I first met Stacy Davis Gates when she was a teacher and they were trying to close her school and I was an organizer with SEIU Local 73. The long term nature of the relationships and the work is really critical.

The work over this time – part of what’s been really clear is that it’s less about the issues that we work on but really the shared ideology is really critical. So shared analysis of why are things the way that they are and how do we understand our role in taking on both racism and capitalism and obviously the intersections of those two and how that is impacting and hitting people in our communities, our workplaces and our schools. That intersection has been a really critical place for us to do transformative work. Our demands have moved from stop the cuts to going on offense to talk about the vision of what is necessary and needed in our city.

So when the moments of the bargaining come along with this last contract, it built on years of talking about housing, affordability, displacement, revenue, economic development and racism in our city.

Stacy Davis Gates (excerpts): We’re a 12 year overnight success. I say 12 years because it shouldn’t take you 12 years. A common good infrastructure is critical. Educators are common good practitioners. So the very basis of what we do is common good, so why wouldn’t we bargain for that? We know that test scores only tell us the socioeconomic and racial background of students. That’s a fact.

We are putting what has become the norm of education on trial. We are part of a community coalition that is seeking to not just shift the way we do school, but shift the way that we see those who need public school. Those are the same people who need a $15 minimum wage. Those are the same people who need affordable housing. Those are the same people who need billions of dollars of investment in their neighborhoods.

This is not something we are doing just for the school communities that our members inhabit. We are actually taking on the premise of neoliberal government, austerity, racism, all of the things that are not going to help us move ahead in the school community, but knowing that parents need stable employment, to be able to afford to live in the City of Chicago.

Marilyn Sneiderman: Why did you fight for common good demands? Why were your members so connected to them?

Stacy Davis Gates (excerpts):Our members are not only working in the school community, driving in neighborhoods that don’t have things, have vacancies in terms our homes that have been torn down and not been replaced.

During the strike, we were able to contrast how the City gave Sterling Bay (developer) $1.5 billion to build Lincoln Yards, the “playground for rich people.” with, meanwhile, in the south side of Chicago we are trying to figure out how to get a nurse and a social worker in school communities that are dealing with poverty and trauma, because, guess what, poverty is traumatic. Not to mention the violence the city has been dealing with for a long time.

We provided that contrast, we told stories of the members of our school communities and we allowed the people in Chicago to make the choice and I would say in that 11 day strike people did make the choice.

Sheri Davis: Does having women of color leadership impact the BCG strategy? If so, how and why?

Stacy Davis Gates (excerpts): The Common Good strategy is a benefit for my leadership. What it does is that it provides instant legitimacy for my experience at the coalition table. I am a black woman and I am in labor, there ain’t a lot of us here leading at this level. The folks at the community table are the people whose experiences are similar to my own. I’m also a mother, my children go to the Chicago public school. These are things that help to legitimize my space within the coalition but also helps to amplify my voice as a leader in labor because a white dude whose kids go to school in the suburbs can’t really have that same voice in the same way. I live on the southside of Chicago. I’m not asking for something that I don’t need myself. I’m not asking other people to make a sacrifice that my family isn’t making. So this is a very authentic place that I’m in.

But it also creates some tension. I do still represent labor, so all the pent up animosity and frustration that people tend to have because of how labor tends to be caricatured or has behaved traditionally still winds up in my lap because I represent labor. I reject that, because I ain’t do it and I don’t believe in being punished for things that I don’t do. But I understand it and I am willing to figure out how to create a more equitable space at those tables.

Amisha Patel (excerpts):I think that it is not a coincidence that women of color have played such a big role within the organizations here. Part of it is there isn’t a separation that can be falsely put into different boxes. It is about race, class, gender, being queer, all of this together and having analysis about how multiple oppressions affect not only us as women of color leaders but our people.

I think this is also a key piece of BCG. The approach isn’t just about bread and butter issues within a workplace, but it is about understanding all of the different ways that people are impacted by being who they are and living in their neighborhoods and communities and struggling with all the different levels of disinvestment or abandonment that people experience. So I do think that lived experience is critical in the sense that all of us are really tied up intricately with each other. This is all of what we do as organizers right, this is the whole point. We take people’s sense of individual power and can build a sense of collective power. Rooting that in the real lives of people and women of color in particular is so critical.

For more, watch the webinar.