In Florida, we see every day what happens without strong mass progressive organizations with a long-term strategy. As the director of Power U since 2017, I steward an organization that has been fighting the school-to-prison pipeline for ten years. Every day, it is a fight not to fall into despair or pessimism about what we are up against and to build the conditions necessary to win.

The Chilean journalist Marta Harnecker said, “Politics is the art of making the impossible possible.” This is the essence of what youth organizing is today. The contributions in this issue — guest edited by Scott Warren and Ben Kirshner — provide insight into the ways youth organizers are grappling with the questions all of our movements face today: how do we build organizations with the power needed to actually change the trajectory of society?

Indeed, too many organizations — both youth and adult-led — prioritize advocacy work and mobilizations over base-building work. In this moment of cascading social and economic crises, youth organizers are well positioned to strengthen our social movements’ connection to working-class communities — helping to build the base of power we need to win.

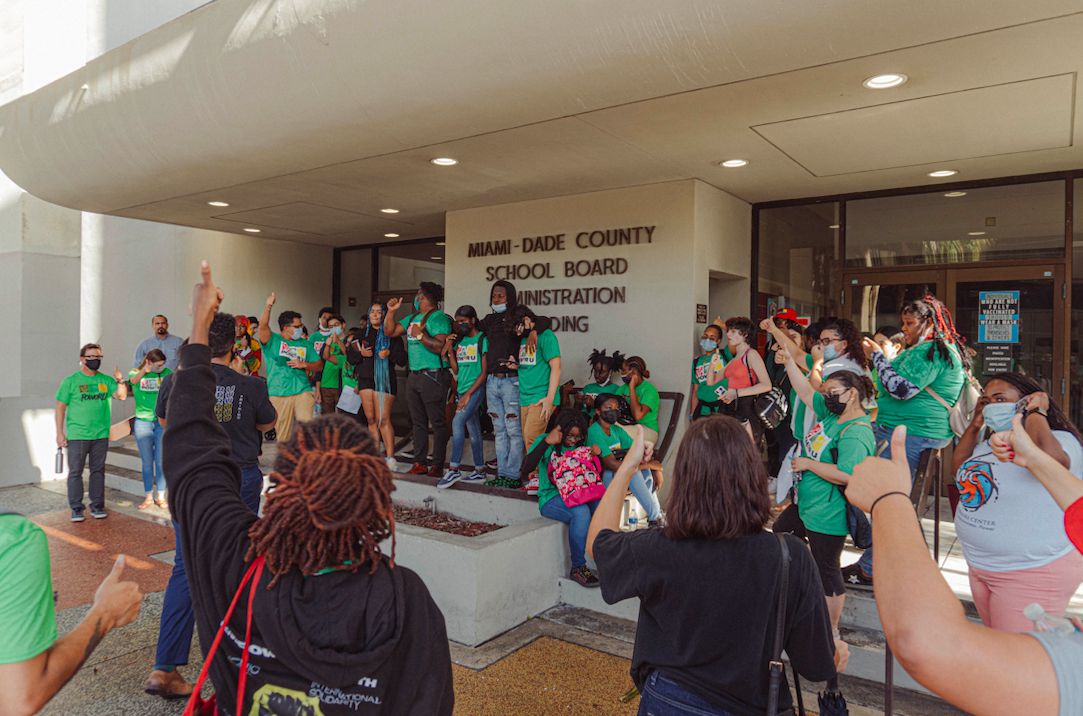

At Power U, we learned the importance of base building the hard way. Our organization develops the leadership of working-class high school students to build and run bold campaigns. After almost a decade of mobilizing and conducting direct actions, we won our fight to end out-of-school suspensions with a commitment from the school district to implement restorative justice practices in Miami Dade County. Yet the district did not actually implement these reforms, and we didn’t have the power to shape the process. Even worse, the campaign didn’t make our organization larger, stronger, or more connected to the working-class communities that we’re situated in. We did not develop our members so that they could take leadership of the organization; as staff, we often found ourselves taking on most tasks because it’s “what we usually do.” We slowed down our programming and took a step back to actually assess our impact. The process unearthed disagreements among our staff about how rigorous a youth organization can be. When we made the decision to adopt a more rigorous organizing program, some staff realized that this wasn’t the kind of work they wanted to do and left the organization. The ones who stayed decided to shift our practices — doing one-on-ones, list building, leader mapping, and coaching — to move the organization forward; in the process, our team of young organizers (all of whom are in their twenties) also developed their own leadership and commitment.

Youth organizers across the country are struggling to develop the organizational practices that we need to contest for power at this moment. We all need to change our practices if we want to win by prioritizing fundamental organizing skills, redefining the scope of our organizing beyond young people, and running campaigns that actually prepare our members to lead. As we see from the various reflections in this issue, many of us are hungry to take on these challenges. How can the field meet the moment?

Prioritize fundamental organizing and organization-building skills.

Most youth organizers are actually practicing advocacy work, not organizing. This was the case at Power U until recently. Most organizing work and strategic thinking was held by paid staff, with members taking on tasks related to mobilizing and sharing personal stories with lawmakers and press. In order to address this imbalance, our organization returned to the fundamentals: training youth leaders in rigorous organizing practices, such as conducting one-on-ones, mapping other leaders, peer coaching, and running strategic campaigns. When we recruited new members, we set the expectation that they would do real organizing rather than just come to meetings to share opinions. Though some left at the beginning of this culture shift, we ended up building a membership that was more rigorous and clearer about the purpose of the organization.

Our organizing staff had to shift their work priorities to account for the additional time needed to support, prepare, and push members to organize in a rigorous and methodical manner. This meant members actually having their own lists and plans to cultivate relationships with residents they met while door knocking. It also met coaching each other when we faced challenges like meetings with low turnout or stress from life pressures. Trying to increase the organization’s discipline has been uncomfortable at times, requiring us to push our members (and ourselves) to confront their anxieties and narratives about what they can and cannot do. But we must prioritize these practices over providing only social or supportive spaces where members feel a sense of belonging. We must challenge young people to step into their own leadership and invest in building a culture that prepares them to show up even when they are under pressure. Because of the shifts Power U made, our elected leadership manages the maintenance of membership and moves our campaign work forward. Our work is also more intergenerational. While a significant amount of the labor is still held by paid staff, shifting responsibility to our youth members made it clear that they can do deep base-building work alongside us.

Power U is not alone in returning to organizing fundamentals. The members and leaders of Youth United for Change in Philadelphia similarly rebuilt their organization by recommitting to base building (lessons they share in Y’all Tryna Win or Nah?!). More broadly, the sector is in a position to develop working-class youth leaders who are not just skilled in advocacy and mobilization but know how to base build and develop other leaders — creating stronger organizations in the long term.

Shift our orientation from “youth organizing” to “young people organizing anyone needed to win.”

If we are to increase the viability of the field, we have to do away with the whole notion of youth organizing. We need organizations that prioritize developing young leaders as part of a commitment to long-term movement building. However, youth organizing in the United States is often isolated from the broader social movement ecosystem. “Young person” is a temporary identity; restricting our organizing to young people hampers our ability to build a bigger “we” and limits intergenerational collaboration. In extreme cases, adult staff serve only as allies, which means young people are not challenged but supported to do whatever they feel most comfortable doing.

When I first began to work with members of Power U, some wanted to conduct direct actions on school board members without meeting with them or conducting research on their positions. “We don’t need to meet with people who aren’t ever going to listen to us,” they argued. “Teachers aren’t ever going to work with us.” Their positions intensified when they returned from youth conferences, where they learned about the way adultism shows up in our movements. This orientation often leads youth organizers to develop a theory of change that severely overestimates the significance of the moral power of young people in political work and fails to prepare them to build other kinds of power that are necessary to win real change.

At Power U, we decided that we needed a clear intergenerational program that would allow us to skill up our members. We tasked members with door knocking, shadowing staff during one-on-ones, and recruiting anyone (young or old) who could move the campaign work forward. This made it more possible to absorb teachers, parents, and residents who lived in our targeted area rather than just those who were already activists interested in our work.

Other youth organizing groups, like UPROSE and Rethink New Orleans, have been doing intergenerational work for a long time. Members of Rethink New Orleans, for example, are trained to think about who we need to win; whether or not they are young is not an issue. Building intergenerational organizations — with a focus on youth leadership development — allows us to lay the groundwork for intergenerational mass organizations.

We must focus on campaigns that develop our people to build long-term power and organization.

Campaigns are often the lifeblood of our organizations, but we should view them as building blocks for longer-term struggle — not an end in and of themselves. Youth organizations, like our movement more broadly, do not currently have the power to dramatically reshape education, let alone society more broadly. We must choose campaigns that allow our communities to envision an alternative future and make bolder demands, otherwise we risk being stuck in a defensive posture.

Running small or symbolic policy campaigns for the sake of the win does not help us step into the urgency of the moment. As I mentioned above, Power U won a campaign in 2015 to end out-of-school suspensions in favor of restorative practices, but we didn’t have the governing power to control or shape the policy’s implementation. We quickly realized our win — which we had been fighting for for almost a decade — was a symbolic one. The campaign also made our organization hyper focused on restorative justice as a framework, which had unintended consequences on members’ political development and understanding of the organization. When asked, some would say Power U was a restorative justice organization rather than one seeking to build power for our communities. We realized that we were too focused on the campaign itself and had failed to develop our members’ organizing skills or their understanding of power and long-term strategy.

One way we have attempted to address this gap is by running issue campaigns that focus on the local budget process. Our restorative justice work never had a beginning or an end; it took almost 10 years, which is longer than the average time a member is in our organization. Many of the members who started the campaign didn’t finish it, creating a dynamic where only staff carried institutional knowledge or purpose. Using the budget as the basis for our campaign has given members more concrete expectations on mobilization timelines and sharpened their assessments of the power local elected officials have. Budget campaigns have also allowed us to train members on clear cyclical phases: a recruitment phase, member orientation, listening campaign, mobilization (during budget hearings), and evaluation. Members feel the pressure of a concrete campaign timeline and can see whether they have made an impact by reviewing the budget. As a result, we are able to evaluate our work each year and determine what we need to do differently the following year.

If members stay in the organization for more than one year, they begin to gain deeper knowledge about how the county organizes its resources, which allows them to take on more leadership. Their focus moves beyond the individual campaign goals to broader questions about which programs get funded and who decides. In turn, they gain a political education about the role of privatization and austerity measures in gutting public education and other social programs that benefit their families. A youth organizing field that chooses campaigns with leadership development, political education, and long-term strategy in mind has the potential to build working-class leaders with an eye toward winning governing power.

Conclusion

We are facing multiple political and ecological crises. Meeting this moment will require more from all of us: a rigorous assessment of our work; an honest evaluation of our political clarity, practice, and organizational strength; and a willingness to take risks by doing things differently, especially when our acclaim within the social movement world has allowed us to stay complacent. This is challenging work, but it will help lay the groundwork for the fight to build an alternative society. Our ability to win this fight depends on the leadership of working-class young people. Investing in their organizing potential will help us chart the path forward.