Introduction

We’re in a union moment –– and that’s an understatement. The conditions to form or advance a labor union in the United States are as good as they’ve been in many generations.

People who work in an array of jobs and geographies are turning towards unionism in staggering numbers. The oppressive status quo –– in some cases stretching literally back a century or more –– is being dynamically challenged by workers in auto, fast food, athletics, and education, among many other industries. The victories are mounting.

Still, there is so much left to be done, and the time to do it is finite. This moment of opportunity for working people and unions won’t last forever. How it will play out remains up in the air. What we do, how we do it, and what horizon we aim for matters.

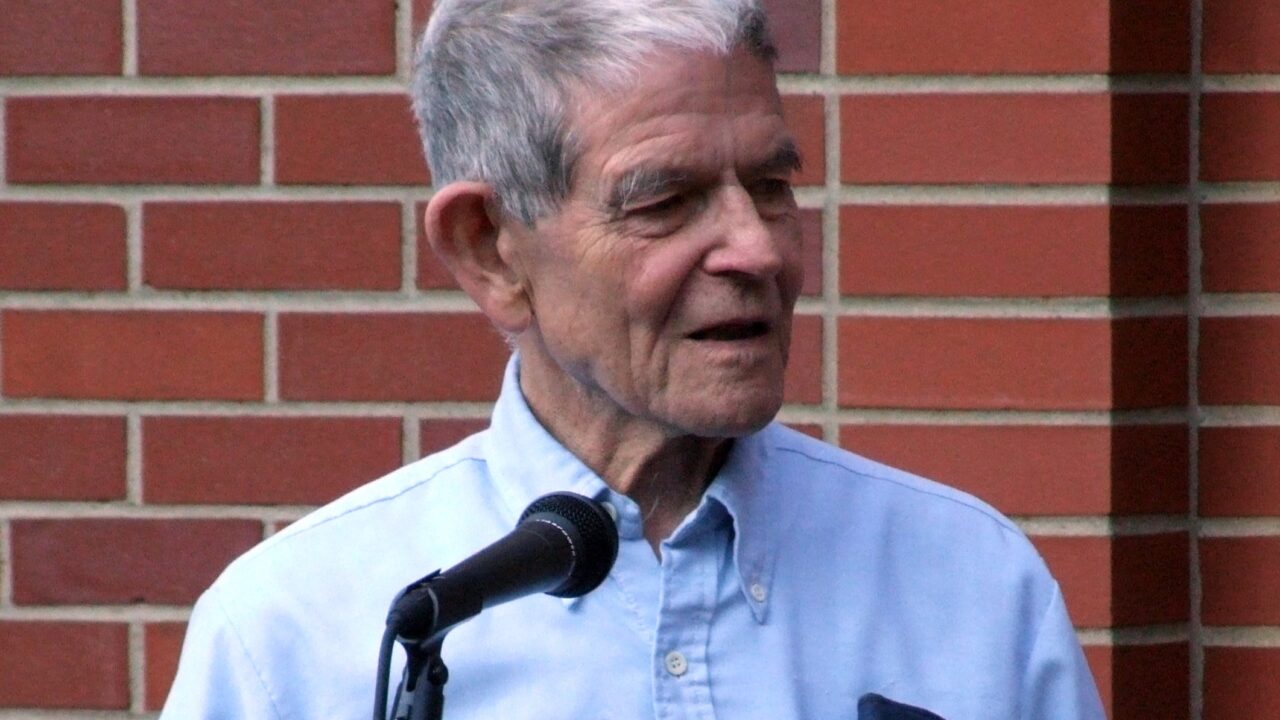

The labor movement and several others movements lost a legend and a beautiful soul in November 2022 when Staughton Lynd passed. Lynd had been advancing the cause of workers all the way to the end of his life at 92. He had been called a living saint by many who knew him or his work. And if there was such a thing, he certainly would have been one.

The breadth of Staughton’s life-work was astoundingly broad and the obituaries in the wake of his transition were too. He was a key figure in designing and helping carry out SNCC’s Missippi Freedom Summer, a storied Civil Rights movement popular education project. Staughton was an early and influential participant in the movement against the U.S. government’s war of aggression on Vietnam. His solidarity trip to Hanoi got Staughton blacklisted from Yale and from academia. The retaliation against academic workers today for standing against genocide in Palestine is an obvious and haunting parallel.

His noted work as a historian of the American revolution and the labor movement –– facilitating its telling and understanding from the bottom up –– inspired countless others in the field. When the steel economy turned to the prison economy in his adopted home of Youngstown, Ohio, he dove head first with his wife and always-collaborator Alice Lynd into the struggle against the carceral state. Most notably, they entered into a deep partnership with the Lucasville Five, multiracial co-leaders of a prison strike for labor and other human rights who were framed up on murder charges in retaliation.

He formed life-long friendships and mentorships with many people including his Spelman college students, the legendary activists, Dr. Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons and Alice Walker and far too many others to name here.

Exiled from the academy and disillusioned by a short stint working under Saul Alinksy, the famous community organizer with whom he clashed, Staughton got a law degree and turned to practicing labor law in Youngstown. Staughton, of course, transcended the lawyer role almost immediately in favor of a fuller type of solidarity he called accompaniment. He lawyered, organized, mentored, convened, did oral history, wrote many highly influential books and articles, and generally showed up in the workers’ movement for over fifty years.

Staughton’s Labor Lessons

Staughton Lynd’s ideas, his work, and the beliefs he demonstrated by how he lived his life are relevant, urgently so, for anyone looking to win justice where they work right now and to contribute to fundamental change in society.

To start at the beginning: Staughton came to believe that it was workers who were uniquely suited and uniquely powerful to change the workplaces and industries they worked in and even the world. He had limitless hope in what happens when working people come together in a room to share their thinking and experiences, dream up a vision, and come up with a strategy to make it real.

Many can claim the same belief, but here’s what set Staughton apart: he matched his vision with a resolute and total rejection of any undue restraints on this unique right, power, and position of workers to determine their own destiny. While Staughton did not short-change the many hindrances to effective union-building and societal change, he focused on those that were most readily at hand to change: the encumbrances that had been accepted by the traditional labor movement itself.

Staughton came to his conclusions through a multitude of sources, and, believe it or not, his lifelong inquiry into questions of worker power and union form began as a young teenager. One key source was Staugthon’s historical work first on the U.S. Revolutionary War and then even more importantly a similarly bottom-up exploration of the great worker and union upsurge of the 1930s. This broad work lined up with Staugthon’s favored way of learning and teaching: stories. Particularly personal stories he heard from the great rank and file union builders in the 30s about what they had done, seen, and experienced.

His orientation to deep, long-term, and often beautiful grassroots organizing was no doubt influenced by his time in SNCC generally and in particular by SNCC co-leader Bob Moses, who he revered and who he was arrested alongside. His devoted internationalism no doubt was influenced by his work in the anti-war movement.

Staugthon’s participation in the struggle against the wicked destruction of the U.S. steel industry in the late 1970s and the 1980s was the movement involvement that probably most solidified his labor ideas. It was there and then that he got to see in horrible first-hand detail confirmation of the theories of the great union-builders forty years earlier.

Insights

Staughton was not just a critic, he had a positive vision and program. He observed and collected together threads of worker-led and operated unionism for fundamental change into what he called “solidarity unionism.” We’ll get to what he meant by that, but first what were those primordial cautionary tales –– super on point for today –– that he learned from the workers who built unionism in the United States and what lessons do they stand for?

In essence, Staughton rejected unionism as a form of “representation” in favor of a form directly led and operated by workers in their workplaces and industries. This is not to say that Staughton counseled workers to go it alone without the support of folks not employed alongside them in their industries. But no one could replace workers as protagonists, the unrivaled decision-makers in their unions, and the constituent which predominantly carried out the work of the union.

Staughton would highlight –– vehemently, repeatedly, and across many decades –– three provisions of traditional unionism he saw as emblematic of its failure to help usher in an economy and a society where a significant portion of workers had their needs met: the management prerogatives clause, the no-strike clause, and the union security clause of collective bargaining agreements.

The key testimonials from workers which planted the seeds for his position are contained in the highly influential collection of oral histories that he and Alice edited called, Rank & File: Personal Histories by Working-Class Organizers.

The testimonial in that volume from Jesse Reese, one of the great rank & file union-builders in steel in that critical 1930s period, indelibly shaped Staughton. Reese liberated himself from a Mississippi chain gang and ended up working in the Midwestern heart of the steel industry. He began union organizing in his mill and then his industry. It was an epic struggle with employers but also internally within the union because of anti-Blackness.

Against the odds, the bullets, and the company spies, Jesse and his co-workers prevailed, ushering unionism into a dominant industry of the United States at an almost incomprehensible scale. To get there, he had endured the Memorial Day Massacre.

When Reese told his story to Staughton over a generation later, the tragedy he emphasized wasn’t the legendary police killing of striking workers he barely survived. It was the tragedy of a union built by workers as an assertive force for workers that had been subsumed by a representative structure that took away workers’ agency.

“I had always said I wanted a union that would be a watchdog for the working class…. So I always called our union the watchdog,” Reese said. But he continued, “today we have in our unions a pet dog…” Reese went on to say, in words that Staughton would share for a half-century, “your dog don’t bark no more…”

The clause that Jesse singled out in the demise of the union he helped build (but later quit in disgust)? No-strike. Your dog’s, “teeth have been pulled out — That’s the strike clause.”

To fully understand Jesse Reese’s heartbreak, you have to know that he and many others saw unionism not solely as a vehicle for improved wages and working conditions for a stretch of time, as important as that is. Rather, he saw it as a vehicle to contribute to racial justice, to a peaceful world, and to enduring economic justice for all.

“If I ever had a chance I was going to turn my dog loose on the steel corporation. I always looked at Mississippi and Alabama. The lynching, Jim Crow, and segregation always stayed on my mind: How could we stop it? My aim was to do it…[T]hey’re now dancing on the doorsteps of Asia, and your dog don’t bark.”

John Sargent, a successful union-builder and comrade of Jesse Reese’s from a different mill, was another worker and union-builder who shaped Staughton’s thinking immeasurably about unionism with and without encumbrances to worker self-activity and direct action. What landed with Staughton was the following testimonial included in Rank & File:

“Without a contract we secured for ourselves agreements on working conditions and wages that we do not have today, and that were better by far than what we do have today in the mill… If their conditions were bad, if they didn’t like what was going on, if they were being abused, the people in the mills themselves — without a contract or any agreement with the company involved — would shut down a department or even a group of departments to secure for themselves the things they had to have.”

It was yet another gifted rank and file union-builder, Sylvia Woods, who helped Staughton adopt what would be one of his most controversial views. Woods was employed at an aviation manufacturing facility during WWII. Later in life, she’d help start the Black Panther’s free breakfast program and health clinic in Chicago.

Woods told of the high-participation union she helped organize at the factory. There were union meetings every night, department by department, where workers shared information and socialized after their shift. 90% of the workers at the large plant were union members.

All that membership was voluntary. There was no union security where, by virtue of an agreement between an employer and a union institution, workers must pay into a union. In mainstream labor, even the left wing typically considers union security a great and necessary thing. With those provisions, a union can most readily retain a membership and receive dues from it.

Woods’ experience with and co-leadership of a dynamic, fighting union at work led her to the opposite conclusion. Staughton would return to her words often over the long haul:

“We never had check-off. We didn’t want it. We said if you have a closed shop and check-off, everybody sits on their butts and they don’t have to worry about organizing and they don’t care what happens.”

These anecdotes line up with a historical reality on a national scale: By the latter 1940s, the dynamic worker-led unionism of the 1930s had been subsumed into an establishment unionism. The traditional unions, led by officials not employed on the shop floor, gave up both the vital right to strike and the struggle over control over production in return for mandatory dues payments from workers and a junior varsity seat at the establishment table.

The benefits of that establishment unionism accrued disproportionately to white male industrial workers. Critically, as the heightened anti-unionism of what is known as neoliberalism became ascendant in the 1980s, the establishment was able to dismantle many of the gains workers and unions had made because the dominant union model was so dependent on the establishment.

What in the world does Staughton’s worldview informed by the 1930’s union-builders and confirmed by history have to do with your decisions as a union-builder today? The traditional labor model which consolidated its dominance by the later part of the 1940s is the very same mainstream union approach of today. You have a judgment call to make: Will a model that was designed to tamp down the agency of workers and avert fundamental social change somehow turn out differently this time if we can only build it back bigger and better? Or are we better off going with other models? Ones that refuse to give up basic workers’ rights and that aim head on to make the changes we need for reliable economic security and a livable planet.

Solidarity Unionism

The threads of unionism that Staugthon was for he gave a name to: “solidarity unionism.” The starting point for Staughton’s solidarity unionism as he relates in his book, Solidarity Unionism: Rebuilding the Labor Movement from Below, is democracy. This meant unions that were led and operated by workers in their industries and not by chain of command hierarchies under a top elected leader as found in traditional unions.

The second fundamental after deep democracy in Staughton’s solidarity unionism was an unmistakable preference for direct collective action by co-workers. In his historical, grassroots, and legal work he simply found no other force more capable of winning and more conducive to workers developing as their agency. Direct action was the counterpoint to a unionism where the exclusive collective bargaining agreement with the nearly inevitable pro-employer provisions I covered above were sacrosanct above all.

Here I should dispel a common and important misconception that often arises about Staughton’s thinking on solidarity unionism. He was for unions holding their gains with written agreements or without written agreements as they saw fit. He was not against written agreements per se. Staughton was against agreements with pro-employer provisions and he was against exclusive contracts where one and only one union had the entrenched legal right to represent all workers in a given part of a company.

The third and last basic operating principle of Staughton’s conception of solidarity unionism was that a union came about when workers formed one. Full stop. Whether the government had issued a certification for the union or the employer had recognized the union were separate matters. If workers through their organization asserted power together to get what they needed –– and either did not want or could not get external validation –– they were a union all the same. One great implication: you wouldn’t lose your union membership just by moving from one job where the union might be establishment-certified to one where it might not be.

Staughton found solidarity unionism of course in those early 1930s rank & file unions but he tracked its antecedents elsewhere, stretching back to the latter part of the 1800s and exemplified by the movement that led to the signal Haymarket moment. But it was in the 1910s and early 1920s that Staughton saw the most direct seeds of the 1930s surge in the form of the solidarity unions constituting the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

The IWW was a central example for Staughton in his conception of solidarity unionism. One of my cherished collaborations with Staughton, alongside the great labor cartoonist Tom Keough, was a graphic pamphlet, called Solidarity Unionism at Starbucks, about the IWW union that held power at the world’s largest coffee chain for well over a decade starting in 2004.

Quite dramatically different worldviews can still make at least a somewhat plausible claim to fall under the umbrella of socialism. Then there’s an even larger array that identifies as socialist where there is no plausible claim as such. In Solidarity Unionism, Staughton held that socialism was a key pillar of this union form right alongside democracy — he called it the “only practical alternative to capitalism.” In a nod perhaps to the dramatically diverging views that are said to be socialist, he argued that the task in solidarity unionism was to define what kind of socialism should be pursued. Staugthon was for an internationalist and liberatory socialism, deeply rooted in worker and community control across religions, races, genders, and ethnicities.

Staughton, to be sure, did not argue that alignment with socialism was a prerequisite for a worker to engage in the solidarity union tradition, far from it. Nor was being socialist a litmus test for whether a union could be a solidarity union. In my interpretation, solidarity unionism does at least require a view of the interconnectedness of the global working class as a whole, not just a narrowly defined membership. It does require some vision of change that is fundamental and not merely cosmetic in an industry and in a society.

Staughton’s internationalism reflected a deep and long standing commitment. His consistent and multifaceted solidarity with Palestine –– one of Staughton’s books is a collection of oral histories he and Alice documented there with Sam Bahour –– was reflected in the outpouring of grief and love from the Youngstown Arab American Community Center contingent at his memorial. The liberation movement in Nicaragua was another key commitment for Staughton and he and Alice made many trips there including at the height of the U.S. government’s war against its people. The Zapatistas were a major influence on his thinking.

Indeed, if there’s one clear mandate Staughton left to us, it’s that unionism must be internationalist. He would be deeply be inspired by the University of California workers who struck to protect the right to oppose genocide in Palestine. To boot, it was a strike that refused to worship a no-strike clause and a strike with clear seeds in an outright wildcat at UC Santa Cruz a few years earlier. He would want the sparks from these strikes to inspire workers widely.

In this context, I would be remiss in sharing insights from Staughton if I didn’t mention two of his mentors and friends who influenced him greatly and who he referenced all the time: Marty Glaberman and Stan Weir –– both working class intellectuals as well as industrial workers turned labor educators.

Glaberman was a close collaborator of the revolutionary, writer, and theorist C.L.R James, author of the landmark work on the Haitian Revolution Black Jacobins and many other vital works. James’ conceptions of worker self-activity and direct democracy are unmistakable in Staughton’s labor thinking. More directly from Glaberman, Staughton sharpened his critique of contractualism, traditional unions as stabilizers of capitalism, and the role of the union hierarchy in enforcing restrictions on worker agency. Staughton wrote the introduction to the collection of Glaberman’s work, Punching Out and Other Writings.

The major concept that Staughton adopted from Stan Weir was the informal work group. From his work and thought as a sailor on shipping boats as a longshoreman, and as an auto worker, Stan observed that co-workers always had organic structures through which groups would move together, make decisions, and implicitly select leaders. For Stan, it was the shop floor and the workers on it, not representatives in a union hall or office away from the workplace, that were the proper venue and constituency to lead and operate a union. Weir’s writings are collected in Singlejack Solidarity including an oral history that Staughton and Alice documented from him. The opening chapter of Single Jack is a poignant and reflective essay by Weir about his friendship with James Baldwin and the extraordinary solidarity with longshore workers that Baldwin engaged in against union bureaucracy that came out of their friendship.

Other important influences on Staughton were also enduring friends and the most frequent visitors to the Lynd basement. Ed Wells, the warehouse worker and rank and file leader in the Teamsters National Black Caucus; Jim Jordan,the militant steel worker and poet of the working class; and Mike Stout, the noted rank and file leader at the storied Homestead Steel mill for whose book Staughton wrote the Afterward.

Labor Law

Some of Staughton’s most influential work and important lessons are in the arena of labor law. Legal can be one of the trickiest parts of union-building to get right, and the pitfalls are enormous. Turning to co-workers, including ones reluctant to talk and embrace solidarity, is hard. Standing up as co-workers to the employer who issues you the paycheck you rely on is scary. We’re taught that lawyers are where you go to solve social conflicts or advance justice. We live in a society where working class intelligence, decision-making ability, and leadership is demeaned.

It’s incredibly tempting then, even at the level of the subconscious, to see our struggle as a fundamentally a lawyer, court, or National Labor Relations Board thing.

Staughton and I were completely aligned on the danger of placing law anywhere near the heart of a union-building effort. We lay out our thinking in Labor Law for the Rank & Filer: Building Solidarity While Staying Clear of the Law.

It is news to many workers getting into unionism that companies can and do break labor law with near impunity. Legal remedies for employer misconduct often never come and when they do they’re far too little and too late. A little more subtly, the legal and bureaucratic process tends to subsume our campaign timeline and our energy into its timeline and its (dreary) energy.

Staughton held that it was workers who clock in and do the work who had what it took and were far better positioned to do the work of unionism than lawyers. He counseled an undeniable preference for direct action which takes place on a playing field where workers are strong (the workplace) rather than the court system which fundamentally upholds the wealth extraction regime of capital owners.

The way to stay safe in a union campaign and preempt retaliation is solidarity with our co-workers, a powerful strategy, and the energy to carry it out. That is not to say that legal actions can’t play a role. Specifically, Staughton believed that Unfair Labor Practice (ULP) charges filed at the National Labor Relations Board could add benefit to a direct action strategy. But the ULP would need to be a marginal part of that strategy, a side thing.

Staughton was in favor of the National Labor Relations Acts insofar as it spoke to collective rather than individual rights and purportedly protected the right to strike. He was very critical though of the part of the NLRA that dealt with government certification of a single union for a particular part of the workplace. Staughton felt that it would inevitably lead to a top-down, unresponsive unionism that over time would falter as an authentic vehicle for workers’ own will and power.

Whether to take a pathway to union gains that includes either NLRB certification or employer recognition or avoids them outright is a key question facing many workers turning to unionism now. It’s worth noting that solidarity unionists differ here. All solidarity unionists are united on the preference for direct action and the existence of a union if workers have formed one, regardless of external validation like employer recognition. All solidarity unionists are united in that campaigns whose furthest horizon is exclusive representation contracts that give up the right to strike and management prerogatives are outside of the solidarity union tradition.

However, there’s arguably a middle ground of seeking employer recognition or NLRB certification and going for a non-traditional agreement that keeps out provisions which tamp down on worker agency and power. Staughton’s belief was that exclusive representation was a sort of monopoly for a union institution over a given group of workers and would disfavor that middle ground. Personally, while I agree that the “purest” form of solidarity unionism would avoid certification and it’s a superb option for many union models, I am also eager to see more learning through struggle by campaigns that get recognition but negotiate dramatically different collective agreements than the traditional ones.

To leave no doubt that Staughton’s influence on law and organizing was enduring, he was just shy of his 90th birthday when the New York Times reported on the appeal of Labor Law for the Rank & Filer to a new generation of unionists.

Carry it On

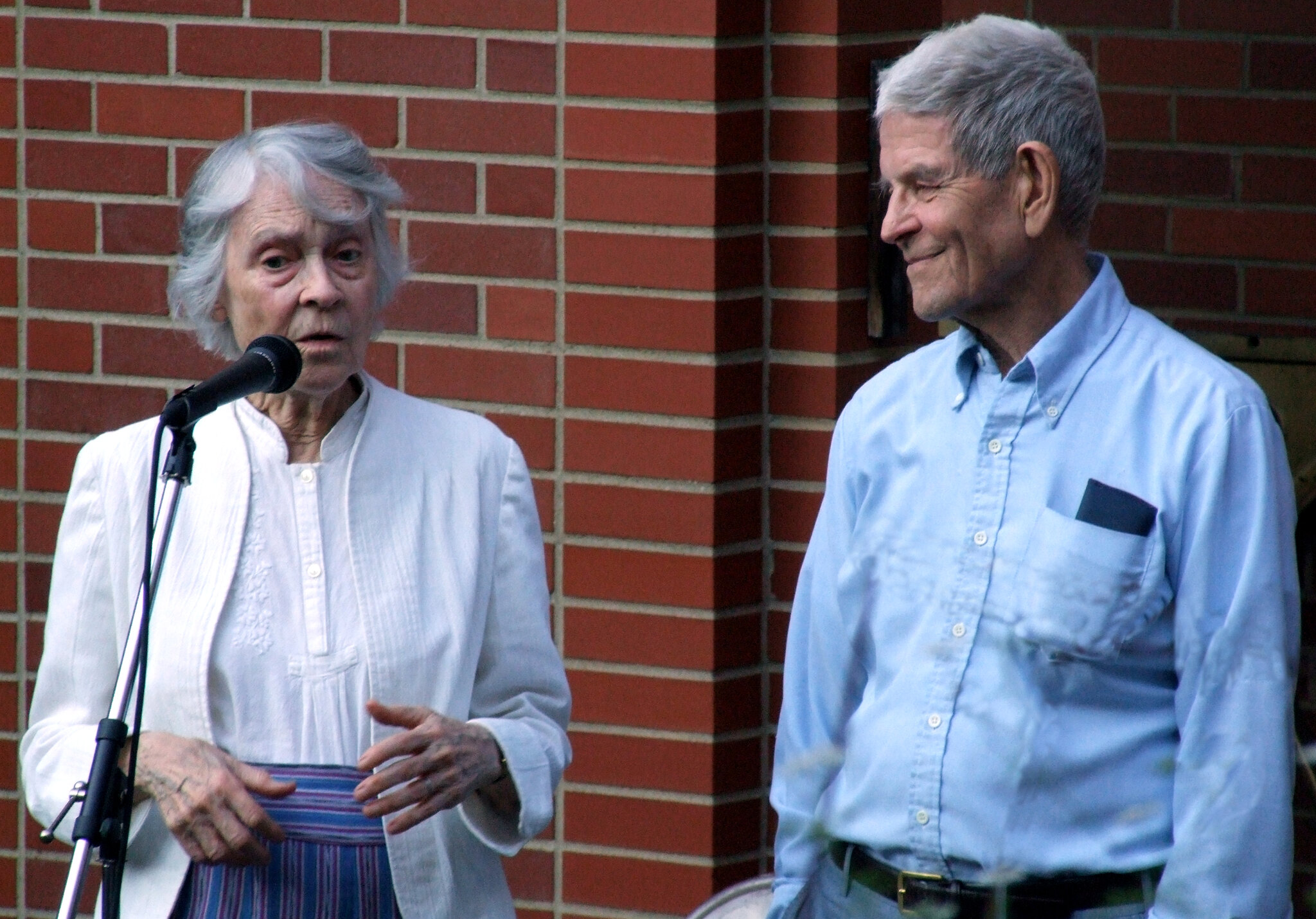

Relationships were central to Staughton and to how he thought about ushering in a more beautiful world. His most significant relationship of all was with Alice Lynd, his comrade, wife, co-author, co-thinker, editor, co-parent, and lifetime partner. Alice survives Staughton and in her 90s herself continues to advance their shared mission.

Staughton spoke and wrote often about “carrying on” the movement. He felt vividly the unfurling of successive generations in movements spanning centuries and with a special resonance on their martyrs and long-haul travelers.

To conclude a 2002 speech, he spoke of the departed comrades he was carrying on for, many of whom I referenced above.

He ended by saying:

“You will have the responsibility of carrying on for me. This is as it should be. This is the deepest and most important solidarity. May the circle be unbroken.”

After Staughton’s passing, Alice urged many of us: “carry it on.”

Of course we will.