This fall, schools have been a hot topic of debate, thanks to a pandemic that’s threatened the health and safety of families, students, and educators. Millions of students have had their education and development disrupted, with disproportionate effects on Black and brown students.

Nowhere is this inequity felt more deeply than in rural communities of color. Lack of access to the internet and computers remains a pervasive problem in rural America and exacerbates remote learning challenges for low-income students. Families already juggling multiple jobs cannot provide consistent at-home schooling support, and too many are grappling with health challenges that put school on the back burner.

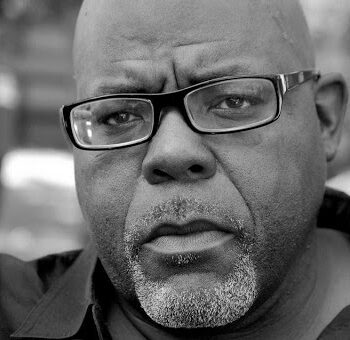

In my own work as an education justice organizer, I’ve long believed that American’s public schools are not failing, they are starving. What I learned from Jitu Brown, Chicago-based community organizer and passionate advocate for education equity, is that organizing and advocacy in Black and brown communities is dramatically under-resourced as well. I spoke with Jitu as well as some of the amazing women leaders in the Journey for Justice Alliance network as they describe what it’s like on the ground, as parents, education activists, and community leaders.

—Secky Fascione

Here are some highlights from the conversation, which have been edited and condensed for readability. To hear the full conversation, watch the video above.

Jitu Brown, Journey for Justice Alliance

I serve the Journey for Justice Alliance as its national director. A community organizer, originally from the south side of Chicago, love brought me on the west side, so I live on the west side now. I’ve been an organizer most of my adult life. Was really blessed to start volunteering with Chicago’s oldest Black-led organizing group, directly out of the movement of the ‘60s, the Kenwood Oakland Community Organization, better known as KOCO. That’s where I developed my philosophy for independent Black-led organizing, power building, deep relationship building, and also working in coalition with folks across race while maintaining our integrity around racial justice. I always call myself a proud son of KOCO. I joined the staff in 2006 as the education organizer.

Our communities were being ravaged by school privatization. They had been closing schools in Chicago as early as 1999 and we knew, based on the neighborhood I lived in and worked in, that school closings were not about improving education outcomes for Black children. It was about reshaping the urban landscape. Everywhere schools closed, we also saw the loss of affordable housing.

We realized that we’d be stronger fighting together than being isolated. So in 2012, 2013 we formed the Journey for Justice Alliance with 12 cities. We soon realized that while we agreed on what we’re against, we had to also organize for what we’re for. So we very quickly developed a platform around education equity, understanding that the biggest problem in America’s education is its refusal to face itself, the refusal to confront the fact that this system has never desired to educate Black, brown and Native American families in a way that’s acceptable. So we built our platform and began to really deepen our capacity to organize.

Anika Whitfield, Grassroots Arkansas

I’m here in Little Rock, Arkansas, which happens to be the capital city, but I can tell you that we are a big town in a small state. One of our greatest challenges is a public school system [in which] the majority of the students come from low-income or poor family homes, which are disproportionately African American or Latinx. The challenge is that our educators are being made and forced to teach both [face to face and virtual], which is virtually impossible. The parents of low-income and poor children are having the worst time of all because they don’t have computers or tablets at home. They’re being forced to go back to work or being evicted from their homes.

Cristi Rosales-Fajardo, El Pueblo NOLA – NOLA Village

I am the director of El Pueblo NOLA – NOLA Village in New Orleans, Louisiana. I predominantly work with Latinx undocumented, Black, and brown families and youth in New Orleans. Everything that has happened in our community, we are the first ones to respond, either with food, or water, or anything that the community needs. As organizers, there are so many battles that we take for our community that it ends up taking a toll on us. I want to make sure that when we are supporting our community, we also have the support that we need to be able to do this kind of work.

Kandice Webber, Houston Rising

I’m the lead organizer for Black Lives Matter Houston, and I’m a registered nurse. I grew up in the same conditions that many of the kids we’re trying to organize grew up in; without education, I would be stuck. So I feel like the reason that I am able to push against oppression is because I’ve gotten that education. Every Black and brown child deserves that chance.

A lot of our parents don’t have internet access, much less a device for their children. So we’re trying to figure out ways to allow as many children as possible to get that exposure that they need and still have some interaction. We’re looking at maybe doing pods: finding small houses in Black and brown areas, doing short term leases on these small houses, putting computers and a volunteer, one per six students, and helping them learn because Black and brown parents are essential workers.

We think that if we can do something like this, then we give the parents a much needed break because now their kids are somewhere safe.

Sharon Wright Jackson, Texas Organizing Project

When you go into racial equity work, in particular in the Dallas Independent School District, you’re dealing with trauma from the Black community. There’s no safe place. Our Black kids, our Black families, we’re traumatized in the home, we’re traumatized in the school, we’re traumatized in the streets, we’re traumatized in corporate America. One of the things that I was able to do through Justice Serves was to give students a small sense of psychological relief. Among all of the computers, all of the constant pressures, just being able to have a psychological relief, to be at home and to do a coloring book, you know, the types of things that kids should do as a part of their social/emotional development. That’s what we need. We need the resources to be able to touch those families one-on-one, to be able to drop information off to them about COVID-19 and the educational rights that parents have to make choices, whether they are going to stay home or be in the classroom environment.

Cherraye Oats and Kayla Oats-Eden, Fanny Lou Hamer Center for Change

CO: [In Mississippi], we started with the school to prison pipeline because our children were being pushed out of school even in kindergarten. This is what they continue to do to our young Black and brown children today, we’re all in one school district, one superintendent, but we still have that struggle [where] the African American school gets nothing. Right now, with COVID-19, school districts are using our young people. A lot of parents are afraid to send their children back to school. We have a school district that doesn’t even have enough Chromebooks, iPads. You have a community that has less internet access. You have a small district that as of last week had started punishing parents and trying to make their children come back to school by using the truancy law. We also have a welfare system that is kicking parents off of the SNAP program, so you have children that can’t eat a proper meal.

KOE: The government is saying that if the essential workers, the parents, are making either a dollar or $1.50 too much to even receive food stamps. So right now, the organization, by itself, has been trying to give lunches out to the students that are homeschooling because a lot of the parents in this community don’t have a lot of funds coming in to feed their children breakfast or lunches. We’ve been on the ground trying to make sure all of the young people who are school age are being fed breakfast and lunch.

As far as the internet, they still have internet downtown. It’s a white community where their homes are condominiums and for the students that are being homeschooled, some of them are having to walk downtown to get on the internet to be able to get their school work in. And back to the racism issue, we’re having problems with the police officers. When the kids are going to do their school work, they’re being followed, they’re being threatened because they’re down there in that area trying to get their school work in.

CO: We’re trying to do a lot of fundraising locally and on a national level. Right now, I have six families that are homeless due to COVID-19.

Maria Harmon, Step Up Louisiana

There is a privatization plan to take over predominantly Black school districts in Louisiana. They’re targeting Jefferson Parish really hard with school closures, which makes absolutely no sense because when you close that school, you’re displacing these kids to merge with another school just to have a private entity like a charter management organization purchase that very same building that was closed to enroll those very same kids that were displaced in the first place. So it makes absolutely no sense, but it’s all a real estate game that’s happening. The Walton’s, the Koch brothers, all of these major billionaire entities are having a stronghold in the ed reform movement and the privatization movement, which essentially exploits Black and brown families. What I really don’t like is how they are giving out a false sense of ownership to some of these communities and really taking advantage of that, and also, at the same time, excluding the out from really having a true voice in that space.

Read the entire issue on Organizing in Rural America.