Young people from across the Global South have been organizing through Fridays for Future to draw attention to the urgent need to address climate change in their communities. Their organizing is part of a critical shift in reframing the global politics of climate change away from some abstract future and toward its very present impact on the lives and livelihoods of communities in the Global South as well as BIPOC and low-income communities in the Global North. As Fridays for Future MAPA organizer Disha Ravi argues, “The climate crisis is about the Global South’s present, not the Global North’s future.”

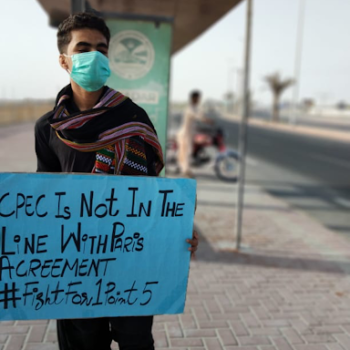

Last month, I sat down with youth climate justice organizers from the Philippines, Balochistan, Mexico, and Bangladesh who are working with Fridays for Future MAPA (Most Affected Peoples and Areas). Each of these activists is involved in organizing on the ground in their communities as well as digitally across countries. Organizing in the Philippines, for example, Mitzi Jonelle Tan works with Indigenous leaders, fisherfolk, farmers, and labor unionists on intersectional issues including local climate change adaptation. Farzana Faruk Jhumu, in collaboration with Fridays for Future Japan, is campaigning against the expansion of coal-fired power plants in Bangladesh funded by the Japanese government. Adriana Calderon is working on a campaign against the Pemex national oil company in Mexico. And in Balochistan, Yusuf Baluch is drawing attention to the climate events — such as flooding, extreme heat, and droughts — that, along with resource extraction, are jeopardizing the lives and livelihoods of communities in the region.

We talked about the potential and drawbacks of digital organizing to build global solidarity, the risks of government repression, and the connections between the climate crisis and systems of colonialism and capitalism. The conversation has been edited and condensed.

Can you all talk a little bit about how you first started organizing around climate change?

Adriana Calderon: I started organizing digitally because it was March of 2020 and COVID was really high. So I started organizing things online with this initiative that we have, Fridays for Future Digital.

Mitzi Jonelle Tan: I got started in activism in 2017 but not specifically on climate activism. I was exposed to a lot of workers’ rights movements, and [the movements of] farmers and fisherfolk and Indigenous peoples. I remember this one conversation with a Lumad Indigenous leader — he was telling us about how they had been harassed and displaced and militarized. Ever so simply, he shrugged and chuckled and said, “That’s why we have no choice but to fight back.” And it was the simplicity of how he said it — I realized he was right. We don’t have a choice but to fight back anymore. That was when I decided to be an activist

Yusuf Baluch: I started working with Fridays for Future because there are lots of problems in Balochistan. I lost my own home when I was a child. My parents lost their homes about 20 years ago when their entire village was destroyed by floods. There are so many similar stories in Balochistan; every year, there are floods and heat waves and droughts. In 2020, I started working with Fridays for Future Digital because I was really afraid to organize physical protests. But later, we started a small group and we started slowly organizing protests.

What is Fridays for Future and how does the network operate?

Tan: Fridays for Future is the global youth climate movement. It’s more of a loose network and a grassroots movement than an organization. I think some people confuse us as an NGO or an organization that has very clear structures, but it’s actually very spontaneous, non-hierarchical, and horizontal.

Fridays for Future MAPA is a subset of Fridays for Future International. It was started because we realized we needed a place where we could talk without having to explain ourselves. Often, what comes with being in a MAPA country are the dangers of the government being very repressive. FFF MAPA right now is mostly activists from the Global South.

How does Fridays for Future connect activists across different places?

Calderon: The open chat has over 1,000 people from different parts of the world. There is this concept of striking digitally — like email storms, Twitter storms — but it goes beyond posting your strike image on Friday demanding something. [Fridays for Future often mobilizes youth from around the world to post pictures of themselves striking on Fridays on social media platforms.] We worked on a campaign called Clean up Standard Chartered where we organized a fake press conference, and I think that is also a really powerful way of digital striking.

Jhumu: Digital striking or actions are a part of how we work together because we are from different time zones and different areas and different cultures. There are some countries, like mine, where physical strikes are sometimes not appropriate. Connecting digitally allows us to organize faster. For example, if something is happening in my country and it is not getting a lot of attention and nobody is really working on it — when there are protests in different countries, our government will respond.

Baluch: It has been powerful to do digital campaigns and reach out to more people. We are highlighting issues which are happening in my hometown or region. It is powerful to protest on the ground because the government feels a lot of pressure from it, but in my area, we have very few people who actually join these protests, so we don’t get media attention. The government prefers to ignore us and the world would be unaware of the issues if not for digital organizing.

What are some of the challenges of organizing in an international network like Fridays for Future? Are there inequalities within the movement, and how are those addressed?

Tan: Just like in any movement or any organization, the systems of injustice and oppression that happen across the world reflect internally as well. So, there are still problems with sexism, or how most of the time it is white activists who are centered, especially by the media. Sometimes it is not even because of the organization or the movement but because of how the media portrays us. The way we address this is by having conversations with different groups, having very strong messaging internationally, and being led by Global South activists.

Jhumu: I think sometimes we feel the guilt or pressure of not doing enough, which connects with eco-anxiety. For example, in my country there are many times I had to talk to people about colonialism in a way that connects it with climate change and other social injustices. These conversations happen at a slow pace. We wonder if we are doing enough and reaching enough people. This feeling lives with us.

Baluch: The climate crisis is deeply connected with colonialism and the exploitation of Indigenous lands, so we need to highlight those issues that are facing local communities on different social media platforms and relate these to international campaigns. We do international campaigns through digital organizing because we can’t really talk about them on the ground. The local campaigns we do are more about climate education and climate awareness. It’s very risky on the ground to do other things because talking against the government or talking about any campaign focused on the exploitation of resources and lands in our region is just like a criminal offense.

All of you attended COP 26 (UN international climate negotiations). What was that experience like as a young person?

Tan: I would say we were impactful in the sense that a lot of the media coverage was about MAPA and Global South activists and reparations and loss and damage. We were able to organize a lot of young people to go out in the streets and do actions with us and meet each other and strengthen relationships and solidarity.

Jhumu: I felt very tokenized because COP was really hectic for us and, when we had interviews, we didn’t have time to check the media write-ups. A lot of people I talked to shared this complaint — that [the media] would only use one or two comments of ours without context. It didn’t actually represent how we said things or how strong our demands were. It was an example of greenwashing.

I know activists face a lot of burnout, and it can be hard to sustain this work or keep it going and growing over time. What are some of the challenges you face in continuing or growing the work that you do either locally or internationally?

Tan: In terms of the dangers of activism, I think it differs by country. For us in the Philippines, a lot of the activists are targeted as “terrorists” — especially the frontline defenders. Our government has a law in which the definition of terrorism is so vague that almost any form of activism can fall under terrorism. And this council has historically tagged activists as terrorists and that has led to a lot of illegal arrests and killings of our activists here.

Baluch: I live in a place which is still occupied by three countries: Pakistan, Iran, and Afghanistan. In the last two decades, we have had many civilians forcibly disappeared by the Pakistani army — including women, human rights activists, lawyers, teachers, disabled people, and elderly people. It is very dangerous for activists, especially on the front lines. When you speak out about issues, you are tagged as a terrorist or a foreign agent trying to change the countries. During our global climate strikes, we were detained by the intelligence agencies four-to-five times. They took all of our information and told us not to do any campaigns publicly because we have been labeled agents. Instead of negotiating with us, they have threatened us.

Jhumu: Our government can access any kind of social media to prevent “terrorism” or to prevent certain protests. That’s the excuse at least, and through that, they can access any of our social media accounts. That’s why we sometimes don’t feel very safe on our digital platforms. It doesn’t actually stop us, but it does concern us because this is not only about me or us, it is about the whole activist community.

Calderon: In Mexico, it is a risk to be an activist, but it is not as much of a risk as being a frontline environmental defender. That’s what pushes me to keep going.

The issue with digital organizing as a young activist is that sometimes you don’t know how to establish limits. That contributes a lot to burnout. We have been trying to address that by creating this caring community of people who are willing to help and jump in if you are stressed. I think that also contributes to people being able to come back even after they’ve faced burnout.

What are some of the main priorities of Fridays for Future MAPA in 2022?

Tan: One thing that a lot of people have a lot of energy towards is demanding reparations. There is a strong focus on climate finance, especially with COP27 coming up this year in Africa. Knowing that loss and damages and finance were sidestepped in the last COP, it’s something that we really want to push for this COP. We need to ensure that our countries in the Global South get the finance we need to actually adapt and manage the loss and damage we have experienced. It has been since 2009 that Global North countries promised a $100 billion yearly climate finance pledge, but it’s not happening. And this climate finance should come in the form of grants and not loans. Another concrete step to move towards climate reparations is the cancellation of debt of Global South countries — especially the debt that was because of climate impacts and fossil fuel infrastructure or the COVID pandemic.