Whether it’s funding for public services, affordable housing, or living-wage jobs, no one knows what communities need better than the people who live and work in them. Yet, because our economy and democracy have been hijacked by wealthy corporate interests, very few people in positions of power are listening to us. Instead, political and economic power in the United States has become hyperconcentrated in the hands of a relatively small number of financial institutions, megacorporations, and billionaires. As a result, when we fight to improve our communities, we find ourselves up against some of the most powerful people on the planet.

This reality also creates an opportunity. The concentration at the top means that the same small set of corporations and billionaires are driving and profiting from many different forms of injustice harming our communities. The same people and corporations fueling gentrification in our neighborhoods are also responsible for defunding public education, or profiting from predatory lending, or propping up a racist criminal justice system, for instance. The current COVID-19 crisis, the recently passed federal stimulus package and other response efforts have the potential to intensify their power.

Bargaining for the Common Good is ultimately about bringing concentrated community and labor power to bear on a common set of corporate villains that are standing in the way of the changes we want to see in both our communities and our workplaces. By going up the money tree, we can discover the different ways in which the same corporate and financial bad actors are extracting wealth from our communities. This approach is critical to Bargaining for the Common Good campaigns because it helps us identify shared targets.

For example, when SEIU Local 26 in Minnesota was beginning their contract campaign for janitors and security guards at Target’s corporate offices, they found they could make common cause with organizations like TakeAction Minnesota that were fighting to win a policy known as “ban the box” to ban employers from asking job applicants whether they have a criminal record. This practice was commonly used as a race-blind way to legally discriminate against Black workers, who have higher incarceration rates because of structural racism in our criminal justice system.

Researchers who were working on the campaign learned that the strongest, most influential opposition to statewide ban the box legislation was coming from the Minnesota Chamber of Commerce, one of the state’s most powerful corporate lobbying groups. Target, as it turned out, wielded enormous influence over the group’s agenda and also happened to be on the campaign’s short list of major employers continuing to ask job applicants about criminal records.

When the union workers went into bargaining, they also created a separate table with Target that included TakeAction Minnesota and other community groups like Centro de Trabajadores Unidos en Lucha (CTUL), demanding that Target ban the box on job applications in its stores in the Twin Cities and tell the Minnesota Chamber of Commerce to stop lobbying against statewide ban the box legislation. After a year of campaigning, they won both demands. Furthermore, Target subsequently announced that it would ban the box in all its stores across the country. By fighting together, the coalition was able to score a major civil rights win while also improving workers’ lives.

This is another key reason to go up the money tree: often the decision makers campaigns traditionally target and negotiate with – CEOs, or mayors, or legislators – are answering to much more powerful, deep-pocketed billionaires and corporate interests. That is, while they have formal decision making power, they are mediating between the concerns of communities and those of corporate power players, and frequently are far too beholden to the latter. This is the basic configuration of power given the structure of our economy and politics, and it has important consequences for how we shape our campaign strategies. Confronting reality is all the more essential in the current moment – those truly in power will try to use this crisis to increase their stranglehold on the systems that control our lives, while we work to address immediate needs.

We have only to look to the groundbreaking Chicago teachers strikes – first in 2012, and then in 2019 – for lessons in how to do this work. Those strikes were guided in part by the recognition that, while school district officials were at the bargaining table and had the power to deliver on some of the unions’ key demands, they were also answering to billionaires and corporations responsible for defunding and privatizing public education in the city. The 2012 strike shone a spotlight on not just Mayor Rahm Emanuel but the billionaire families and corporations who he saw as his most important constituents, including banks that had profited from toxic swap deals with the city and developers that were getting millions in taxpayer subsidies. Focusing attention on these players helped shift the public narrative and build the necessary pressure to win a deal.

In 2019, the strike targeted another mayor, Lori Lightfoot. But while the structure of power had shifted, it had not fundamentally changed – the same small set of billionaires and corporations held disproportionate influence over Lightfoot, and over the life of the city. One central issue in the strike, as with many public sector bargaining efforts, was the city’s position that there was not enough revenue to meet key demands; another key issue was the gentrification of neighborhoods and the growing housing crisis in Chicago, which has played a significant role in forcing Black families out of the city.

You may have guessed, by now, what we’ll say next: the same small set of corporate players were behind both issues, and were profiting from them. The strike focused a great deal of attention on how there was, in fact, money, but it was in the wrong hands, because the city was doling out tax subsidies to billionaire real estate speculators – who were, in turn, using that money to gentrify neighborhoods and drive the housing crisis.

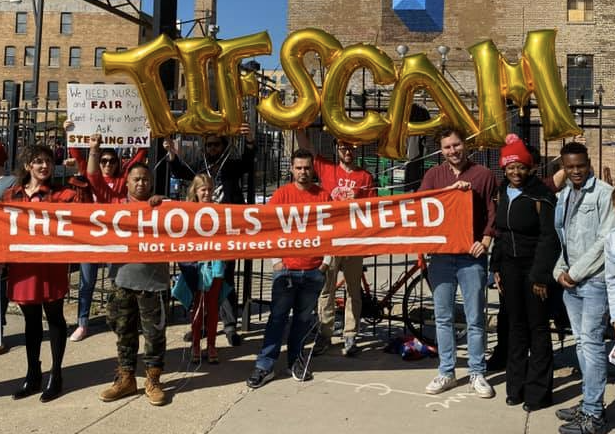

The unions partnered with the Grassroots Collaborative, a community-labor coalition, to build pressure on one of the major beneficiaries of these tax deals, Sterling Bay, which got $1.3 billion in tax breaks for the Lincoln Yards megadevelopment. One of the most powerful moments of the 2019 strike was when nine striking teachers got arrested in a civil disobedience at Sterling Bay’s headquarters, taking the developer to task for driving up rents in the city while also draining the school district of much-needed revenue.

Understanding the ways in which corporations wield power and influence is imperative to identifying the targets in Bargaining for the Common Good campaigns. For example, in the context of the current COVID-19 pandemic, hospital workers can demand that their hospitals provide free testing and treatment for all COVID-19 patients. Auto workers can demand that their factories be used to manufacture medical equipment and supplies during shortages.

Ultimately, Bargaining for the Common Good is about solving the structural problems in our communities and our workplaces. Because of the ways in which political and economic power are concentrated, going up the money tree helps us identify our true overlords so that we can force them to get out of our way.