In 2016, most rural Indivisible group leaders didn’t imagine themselves as political organizers. But they felt the ground shift beneath them and stepped up to meet the moment. At the time, many didn’t know the intricacies of organizing mechanics: the components of deep, values-based canvassing or power mapping, the nodes of a leadership development ladder or a Ganz snowflake model, or the mechanics of running an electoral campaign. Yet they were living and breathing organizing. Many of Indivisible’s rural group leaders are now running for local office themselves, employing the tactics learned through the defensive 2017 congressional fights and the offensive Midterm campaigns.

Ahead of the 2020 November election, we, the organizers lucky enough to work with them, interviewed a few of our rural Indivisible group leaders about their experiences over the past four years, including how they cultivated relationships and built their groups’ influence in their communities, how they’ve navigated everything from the pandemic to leadership transitions, and what they think is in store in the weeks and months ahead.

A special thank you to Indivisible’s rural team, who work tirelessly to support our rural groups across the country: Tricia Sauer, Scott Ickes, and Dennessa Atiles.

CLICK TO HEAR THE ENTIRE PODCAST

INTRO

“We help people have conversations that … build on shared values and remind them how everyone does better when we take care of each other, and that is part of a rural identity. “

Yurie Hong of Indivisible St. Peter/Greater Mankato in Minnesota recognized the importance of creating space in her community where members could discuss political issues as the national climate grew increasingly polarized. Utilizing the foundations of deep canvassing, Yurie’s group supported members in having difficult conversations, grounded in compassion and shared values, within their personal networks. Yurie attributes the current political climate to the Democratic Party prioritizing urban districts over rural areas. Although she knows the electoral returns may not be immediate, Yurie believes that her rural group engages in the difficult organizing necessary for long-term change.

CLICK TO HEAR: Yurie Hong, Indivisible St. Peter/Greater Mankato, Minnesota

2017 | CREATION

“We were tracking legislation, setting up ways for people to contact their representatives while also having a community outreach and education program regarding a new chemical plant, US Nitrogen. We also went door to door and told people what number to call if there was a spill.”

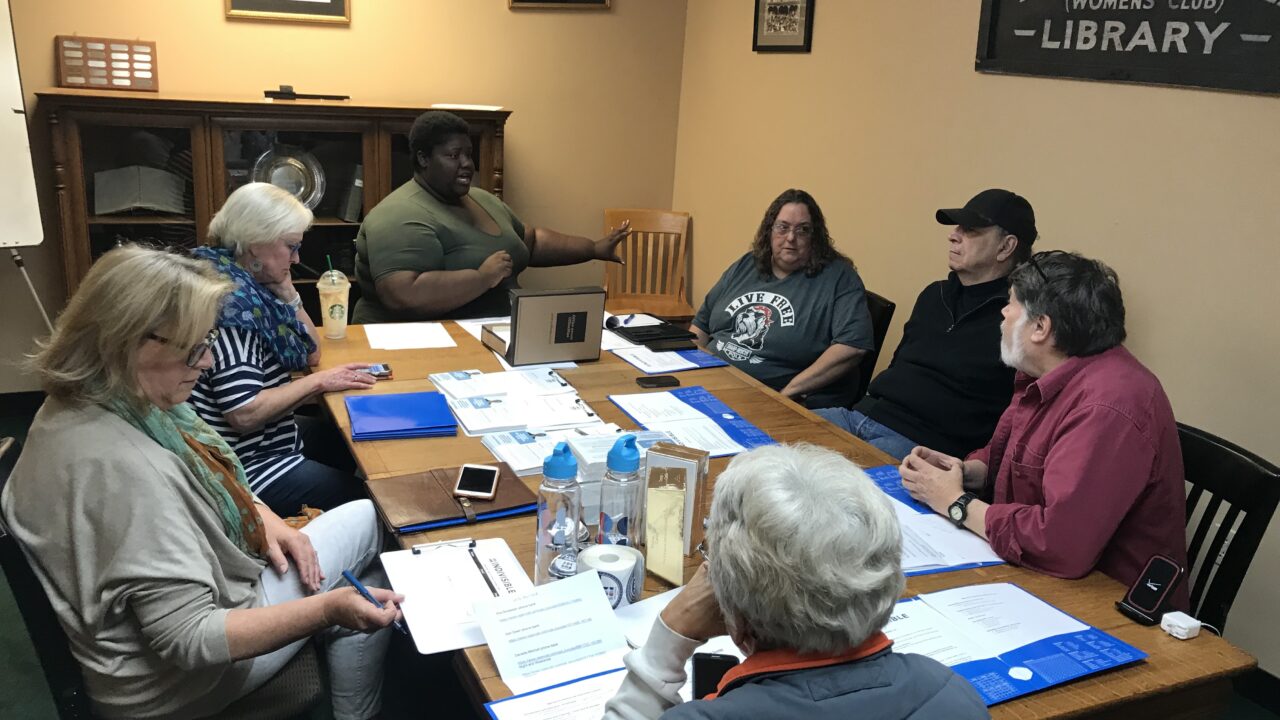

In the aftermath of the 2016 election, Art and Gigi Gillen found themselves searching for a place to channel their anxiety and outrage. They first showed up at the resurrected local County Democratic Party office but soon heard through the rumor mill about a group of like-minded individuals creating an advocacy group called Indivisible Greene County TN (IGCTN). It was a busy year for the group, with a rotating buffet of speakers, protests, and postcard-writing campaigns: an education in Advocacy 101 for those new to organizing and campaigns. Rural groups like IGCTN quickly discovered that, if they wanted to be vocal about the ACA and Medicaid, they also had to generate local social capital to eclipse their anti-Trump aesthetic, which often thwarted local coalition building. Rural Indivisible groups have survived because of this flexibility and ability to balance local and national priorities. IGCTN, while birddogging then Senators Bob Corker and Lamar Alexander, simultaneously ran a local campaign to force the local US Nitrogen plant to install a two-siren system. IGCTN rallied local environmental experts for community meetings and launched a door-to-door canvassing operation, resulting in community goodwill. The group was able to transcend political affiliation because of the shared desire for environmental protections among community members. Although the group still has a progressive brand, it’s broadened its membership and coalition reach through projects like the US Nitrogen campaign.

CLICK TO HEAR: Art Gillen, Indivisible Greene County in Greeneville, Tennessee

2018 | MIDTERMS AND THE AFTERMATH

“What was energizing about our Highlander gathering was getting together in person with other Indivisible groups in the state. We started the rural caucus, and we got excited about that because it felt like rural Indivisible groups have very different needs and abilities than perhaps urban groups.”

Months before the November midterm election, rural Indivisible groups like Norris Indivisible were buoyant as they contacted voters for congressional races. After heated sparring with their congressional representatives over the Affordable Care Act and DHS family separation, rural groups stepped up to support progressive candidates like Dr. Danielle Mitchell, running in the 3rd Congressional District in Tennessee. The rural groups working together on Mitchell’s campaign took advantage of National Indivisible’s endorsement program, nominating Dr. Mitchell and eventually running their own canvases and phone and text banks for her. In states like Tennessee, where the state party does not organize at the congressional level, rural Indivisible groups often fill the organizing vacuum, especially in deeply neglected districts.

The 2018 “blue wave” didn’t reach many states, including Tennessee. Phil Bredesen, a former Tennessee Governor who won every county in 2006, lost by double digits to now Senator Marsha Blackburn. Dr. Danielle Mitchell lost by thirty points. The heavy losses mean that rural groups in Tennessee are still a long way from a statewide or congressional win; however, incremental gains in their counties give them hope for 2020.

Seeking refuge from the election results, Liz traveled to the Highlander Center, the center of movement-building in the American South, for the first statewide convening of progressive rural groups in Tennessee. With support from Indivisible’s National training team and Amy Dudley, formerly with the Rural Organizing Project, the state constellation of rural Indivisible groups executed their first power mapping exercise, laying the groundwork for the national network of rural Indivisible groups established in 2019.

CLICK TO HEAR: Liz McGeachy, Norris Indivisible in Norris, Tennessee

2019 | BUILDING CAPACITY

“We designed ourselves to have three tracks: one was a political track on how to organize to make political change, one was environmental because our area is highly gas welled, and progressive Christians … because churches are still a center of people’s lives….”

In January 2019, Kathy Krouse of Indivisible We Rise – West Pennsylvania, attended a progressive summit in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and immediately recognized the lack of advocacy training provided to rural groups in her area. With support from National Indivisible, Kathy and We Rise organized the first Indivisible Rural Summit in Clarison, Pennsylvania, in June 2019. Bringing together a diverse coalition of rural advocates, including local clergy, the Indivisible We Rise rural summit generated multiple organizing projects, including a progressive faith coalition, which recognizes and leverages the important role of churches in rural communities.

The summit led Indivisible We Rise to reimagine what its organizing could look like. Group members walked away understanding that their intimate knowledge of their own rural communities was a game changer. The structure of their team evolved into a multi-faceted campaign galvanizing neighbors by addressing local challenges and engaging in local politics. The Summit provided the space to identify where community stakeholders were, learn which tactics were working in terms of political education, and develop the skill set (deep, values-based canvassing) to move community members towards engagement.

CLICK TO HEAR: Kathy Krouse, Indivisible We Rise West Central PA

2020 | PANDEMIC

“We pivoted pretty fast for a couple of different reasons. Our group, like a lot of Indivisible groups, is mostly older people … and I knew right away that I couldn’t have us meeting in person. Now we’re having as many people at our monthly meetings … as we did when we were meeting in person. I feel pretty good about that.”

When COVID-19 struck, rural groups like Indivisible Colusa County in California pivoted to meeting virtually. However, Jennifer, one of the group leaders, knew that navigating the technology would be difficult for the group’s mostly older membership. She recounts that half the battle was convincing group members that they could learn the new technology, while the other half was setting up channels to troubleshoot their issues with the platforms. One group member self-selected as the “tech guru” and spent hours providing “Computer 101” training to many older group members. By providing intense onboarding tech support, Indivisible Colusa County has maintained a high number of attendees for its virtual calls and continued its monthly programming of conversations with community leaders.

CLICK TO HEAR: Jennifer Roberts, Indivisible Colusa County

2020 | NOVEMBER

“[W]ith these rural Indivisible groups, you’ll be able to say you tried to do something…. We tried, we did things, we fought against it, and we made our views known. We’ll be able to say that and feel good about it.”

With less than fifty days to the election in the critical swing state of Wisconsin, Betty Koehl from Indivisible Sauk Prairie laments not being able to go door to door. But she knows that rural Indivisible groups, despite the difficult political climate, are stepping up their COVID-safe, direct voter contact tactics, including working with other groups in the state to fund, write, and send postcards through Indivisible’s GROW grants program. Betty plans to retire after the election and hopes to solidify new leadership before she departs. For many rural groups, identifying new members and mentoring them to assume leadership roles is a top priority right now to ensure group survival — especially as we look past the November elections to 2021 redistricting efforts.

CLICK TO HEAR: Betty Koehl, Indivisible Sauk Prairie in Wisconsin

OUTRO

“If Biden gets in, he’s not going to do everything we want him to do, so those would be areas too where we could try to weigh in.”

On the heels of the 2020 election, many organizers wonder what’s going to happen to the 2016 resistance groups, especially if Biden wins the presidency. For Joan McMillin of Common Grounds Indivisible, the organizing continues. The Indivisible members in her chapter plan to continue advocating on local issues and maintaining their reputation as obnoxious gadflies for state representatives. “If you think you are too small to make a difference, try sleeping with a mosquito in the room.” In this interview, she reflects on how her group has made a difference these past four years and the camaraderie that has kept them going. Many of the group’s members have family who support Trump and felt afraid to voice their own opinions. The group provided a place for them to speak about their fears, their anger, and their frustration at living in a red state like South Dakota. Whatever the scenario, accountability, friendship, and a drive to organize are the keys to rural resilience.

CLICK TO HEAR: Joan McMillin, Common Grounds Indivisible in Sioux Falls, South Dakota

Read the entire issue on Organizing in Rural America.