As the National Campaign Manager for Health Care for America Now, Richard Kirsch helped to guide and implement the strategy for winning the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The campaign incorporated a unified organizing and narrative strategy that fundamentally transformed the way Americans think about the relationship between the government and health care. Winning the ACA further drove that narrative change, which was critical to protecting the law when it was under threat in 2017.

Richard now runs Our Story, The Hub for American Narratives, where he focuses on narrative change. He talked with us about movements driving transformative narratives, the decline of dominant right-wing narratives, the unifying meta-narrative the left already has (even if we don’t realize it), and, of course, his work on healthcare and HCAN. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Jonathan Heller: Do you see the COVID-19 pandemic and the protests against police violence as an opportunity for positive ideological or structural change?

Richard Kirsch: Yes, it’s a huge opportunity. It’s also a scary moment, with seven days of peaceful protests and then violence at night. I remember right-wing backlash after the protests in 1968 and 1992. But I’m seeing encouraging signs. Democratic leaders are understanding there’s not a lot of benefit from appealing to the right and looking tough; they have nothing to gain in terms of Trump’s base, and they would endanger their own base. With Black Lives Matter and other movements in the last several years, people are understanding profound differences and truths that we’ve not seen before. It was remarkable to see Democratic presidential candidates talking about structural racism regularly.

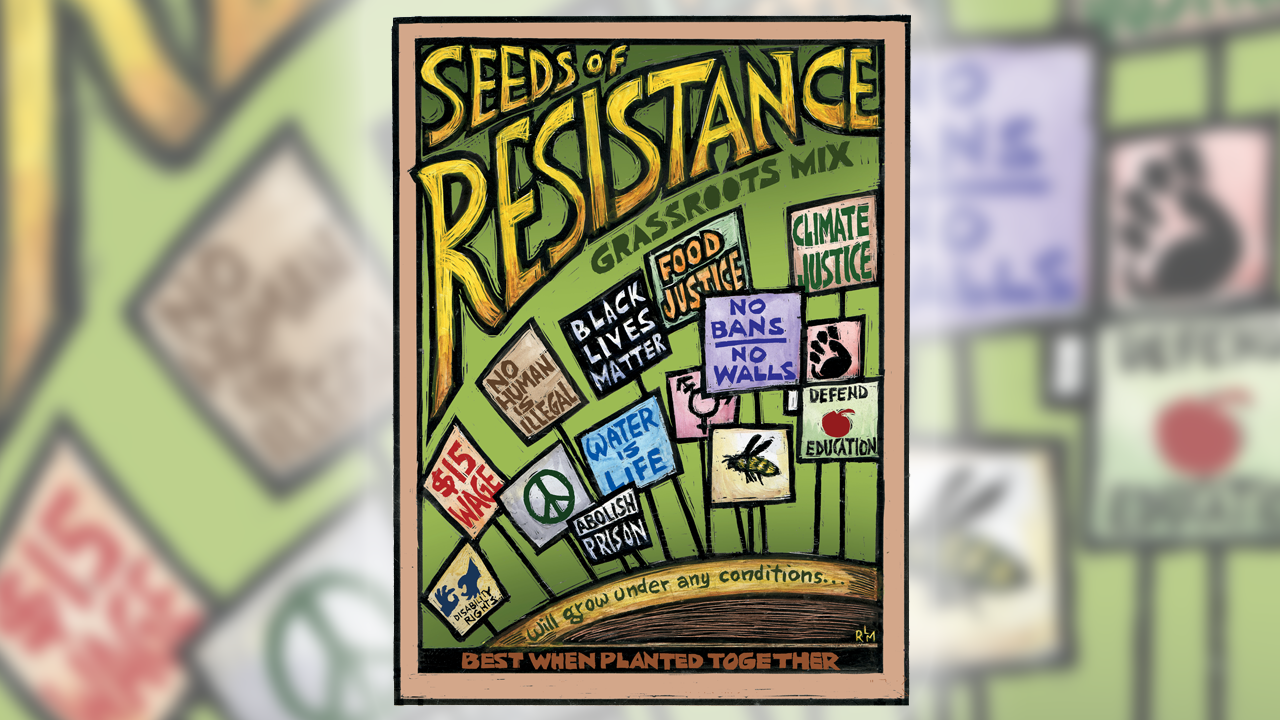

More generally, we’ve seen a lot of movements in the last few years — Black Lives Matter, Fight For $15, the Dreamers, the climate movement, marriage equality — all of which started before Trump’s election. And since then, the rise of the Women’s Movement and #MeToo, Indivisible, young people leading opposition to gun violence. All these have brought a huge amount of energy and people who haven’t been politically engaged before. Right-wing movements like the Tea Party were dominant in 2010, but movements on the left have been dominant over the last seven years. If you look at American history, you find that periods of movement agitation like this precede progressive eras, often without getting the kind of mainstream attention that social media now allows. So I think it’s all really encouraging.

JH: It’s great to hear that you’re so hopeful. What’s the role of narrative in making those changes? Is it important for the left to have a narrative strategy and, if so, why?

RK: The main way we drive narrative is through movements and the stories movements tell. Black Lives Matter is a meme which encapsulates a powerful narrative that drives more change than any narrative I can write about criminal justice, racial bias, and policing. The way people put themselves on the line and the way their actions convey that narrative. It’s similar with the Fight For $15: working people, Black and brown people in particular, were willing to strike and risk losing their jobs at McDonald’s, and that told a story. We saw allies joining them, and we saw that spread to cities around the country. There’s a narrative behind these. Narrative change is driven by underlying ideas and concepts but it’s also driven by these movement memes.

Make America Great Again is a narrative. It’s aspirational and there is a point of tension: Make America White Again. It’s about people who feel they’ve lost their sense of status in society, who don’t have the economic security they used to have.

The same thing with the Dreamers. It’s aspirational but it also tells how they got here, why they became Dreamers. It connects to the American Dream, which they want to live and feel, and through no fault of their own, they’re being denied.

There’s richness in all these. The best short narratives capture all those things in a powerful way. It doesn’t take much to tell a rich story. We should recognize the power of a meme within a movement to tell a whole story that drives social change and changes worldview.

JH: The narratives you develop are different from these memes. Tell us about those.

RK: I use narrative in a more formalized way, based on the three faces of power. The first face of power is around issues, elections, and litigation, the daily work of politics that’s most visible. The second face is around infrastructure, the organizations we’ve built and the relationships between them, which is not as visible.

The third face of power is worldview. It’s the ocean we swim in. It’s how people think of themselves in relation to society. It’s what makes or limits what’s possible. It’s why the policies of Barack Obama and Bill Clinton — Democratic presidents — were to the right of Richard Nixon, who did not have progressive values but who was in office at the end of a progressive era. We were able to pass many things under Nixon that were progressive, like the Clean Water Act. The goal of narrative is to change worldview because that allows politics and issues to change. We need to consistently share a powerful narrative that changes worldview.

A definition of narrative I use is a value-based story about our core beliefs. Values are how we morally make sense of the world. Values tap into a strong innate moral sense people have. Through stories, we organize how the world works, who’s responsible, what do we do about it. In the classic, mythological way, it has heroes and villains and a quest.

The challenge is getting our Left infrastructure to share a common narrative, to repeat it over and over again. That doesn’t mean every word, but it does mean that the same core story is understood and repeated. It needs to be communicated effectively, which means not relying only on facts to convince anybody of anything. We understand the world through emotions, so facts in service of the story are helpful but not what we lead with.

Judith Barish: Walk us through this as it applies to healthcare. Is that an example of how enacting legislation radically shifted narratives about health and the government’s role?

RK: Healthcare is a particularly difficult issue to work on because people have strong emotions about it, and it is therefore politically fraught. The issue is personal and makes people feel vulnerable. People have common aspirations about healthcare: they want healthcare that’s always there, that they can afford, that is high-quality care. With healthcare, as soon as you get into specific solutions, people feel threatened by what they might lose. The healthcare industry, one of the biggest industries in the country, will do everything it can to scare people if proposed changes will take money away from them. We need to keep all that context in mind.

To pass the Affordable Care Act, we had to take people from where they were, assure them they weren’t going to lose anything, and move them to their aspirational selves. The core narrative was: “Quality, affordable healthcare for all, from your choice of a health insurance company that can’t deny you care because of a pre-existing condition, or from a public health insurance option that will put your health before profit.” It starts with an aspiration, a quest: quality affordable healthcare for all. It then names a villain in a way that shows a positive, aspirational role for government in protecting us from that villain and your choice of a health insurance company that can’t deny you care due to pre-existing conditions. That was a powerful narrative that worked to trash the villain, have an aspirational role for government, and give people a sense of control. In our TV ads in the last months of the legislative battle, we used the tag line: “If health insurance companies win, you lose. Quality, affordable healthcare with a choice of a public option.”

When the Tea Party attacked healthcare reform, our response was to attack the insurance industry. When they erupted at the town halls in August 2009 and got press because they were so aggressive, within ten days we were able to turn out as many or more people at those town halls and shut down the Tea Party’s press. The story we told was reminding people that the insurance companies were the real problem. We showed Democractic members of Congress that they had people in their districts at their backs. That was a positive turning point that opened the way for the eventual win. The Democratic Party and President Obama were reluctant to attack insurance companies at first but eventually saw the need as the only way to avoid losing.

The consistent narrative around insurance companies versus government paved the way for what then happened in 2017, when Republicans tried to repeal healthcare. People realized what they were going to lose. Our message was, “Don’t let them take away your healthcare. Don’t let them take away healthcare from 20 million people. Government is actually providing you security that you didn’t have before.” The ACA is now more popular than it’s ever been.

JH: It sounds like you had a narrative strategy that led to the policy win, and then the policy win continued to help people change the way they thought about healthcare and government.

RK: That’s right. And that sets us up well for the “Medicare For All” movement. Millions of people have now lost their jobs and their health insurance due to COVID, and people want the security of healthcare. We should use a similar narrative: “Quality, affordable healthcare for all, through an expanded and improved version of Medicare. But if there’s private health insurance that’s also affordable and comprehensive, you can keep that too.” Because we’re in a more progressive time and because the ACA has lots of failings, I think we could now pass a more robust version of healthcare reform. But it’s a mistake to think we can win single-payer, because the opposition will effectively use the same argument we used to stop the ACA repeal: they will take your health insurance away from you. And no amount of reassuring responses will overcome the fear that will induce. Instead, we need to insist that everyone can enroll in improved Medicare but not require it.

JH: How did you use that narrative and that narrative strategy in the organizing that was being done in the Healthcare for America Now campaign?

RK: We knew we needed to build power outside the beltway to win the campaign. There were a few things that narrative allowed us to do. It allowed us to unite the left. In ’93 and ’94 with the Clintons’ plan, we had tremendous divisions on the left between single-payer people and people who wanted to preserve the private, employer-based health insurance system. We couldn’t afford that split again. By having a public option and by making the insurance industry a villian, single-payer advocates felt comfortable joining. The narrative allowed us to build alliances, including with small business, because they could support the story we were telling. The narrative also allowed us to put faces to the campaign: people who had lost loved ones because they didn’t have insurance or they had been seriously sick themselves and didn’t have insurance. Those drove the story in a powerful way.

The organizing and the narrative were really always one. The policy and politics and narrative were all tied together, all in service to each other, all reinforcing one other.

To be successful, a campaign needs a powerful narrative that drives it, that tells the story publicly. It’s not only a communications vehicle, not just about messaging or what polls well. The narrative is communicated in everything the campaign does. When starting any campaign, organizers and campaigners need to write a values-based story about their core beliefs. They need to lay out their aspirational quest, be clear what the problem is and who’s responsible, and have a clear story about the overall solution and the policies that get you there. We should add a narrative column to the Midwest Academy strategy chart.

JH: That aligns well with what our whole project is about. Let’s take a step back and talk about the right-wing narratives dominant today. Would you describe those and why they’re problematic for us in terms of policy change and power building that we’re doing on the left?

RK: The right’s story is well known. Limited government, shrinking government, cutting taxes, free markets, rugged individualism. It tells you that the free market creates wealth, government that interferes with the free market is the villain, and the heroes are the rugged individuals who drive the free markets, come up with new products, and do the work. It leaves you on your own either to be a rugged individual or to be a failure because you’re not making it. It disempowers people who are struggling and makes them feel like it’s their fault for not working hard enough, though the system is structured to concentrate wealth amongst a few people. And then there is a racialized component. Anybody who’s failing, who’s not doing as well, who’s “dependent” on government, is considered to be weaker. We have structures in society which intentionally push people of color down, but those are made invisible by this narrative. That’s the story the right has told powerfully and it’s one that people still internalize.

But that narrative is not nearly as powerful today. Increasingly, people have a sense that society is rigged against average people, in favor of the wealthy; that government does the bidding of the wealthy and powerful corporations; and that that’s wrong. People believe raising taxes on the wealthy will increase economic growth. People now think there’s an important role for government regulation, for health and safety, to provide economic security so you can retire, and to provide affordable education and child care. People are opposed to cash bail and believe the criminal justice system has tremendous bias built into it. They think government has an obligation to ensure that everyone has a real opportunity to succeed.

The power of the Black Lives Matter movement since George Floyd’s murder has finally helped people understand what systemic racism is about. We’re in a much better place than we were a few years ago, though people are still conflicted. If we tell our story powerfully, we beat their narrative easily.

JH: Do people hold multiple narratives in their head? Do people already know these “new” narratives, but suppress them?

RK: Absolutely. About 15 or 20 percent of people have consistently progressive values and 10-to-15 percent have consistently right-wing values. So, about 70 percent are in the middle. They fall one way or the other more, and the way you make change is to reinforce progressive values for the people in the middle. The more they hear our narrative clearly over and over again, the more they believe it. If we muddle it by telling a story which uses both conservative and progressive values, they’re confused and we’ll be defeating ourselves.

As Anat Shenker-Osario says, people can hear these narratives best from people who have progressive values and repeat them over and over again. They tell their friends, family members, and co-workers. They have to tell the story so it’s not too jarring to those who have conservative values and so it doesn’t sound like it’s from the outside, using jargon, because people in the middle will shut down if it sounds that way. Being the most radical or extreme does not convince people; they don’t hear you. We need to focus on our shared values. Freedom from want, to speak your own mind, to worship the way you want, not to have to worry about going hungry or not having health insurance. Building a society where we’re all able to realize our full potential, regardless of the circumstances we’re born into, regardless of our race, gender, or where we’re from. We can tell that story in a way that’s inclusive and resonates.

JB: As you’re thinking about narrative strategy, do you differentiate between folks on the street versus opinion leaders and political elites?

RK: I don’t ever worry about opinion leaders and elites. The debate within the Democratic Party is much more progressive in 2020 compared to 2016 or 2012. Those opinion makers and elites changed their rhetoric because of the movement building and the energy and the organizing. These ideas have become legitimized with the elites because of that work. We’d never get there by starting with the elites. We only change the positions of elites by building people power and the ability to change who’s in government.

JH: Do you think it’s possible to create a unifying transformative meta-narrative for the left and unite campaigns and movements under that?

RK: I think we already have it but don’t understand it. We have a consistent set of beliefs that we’re not good at recognizing. I do exercises with groups of progressive leaders from different walks of life. I ask them to talk about their quest, the problems they see, the kind of world they want, what their values are. Every time, I get the same answers.

You can encapsulate it like this: We want a government and economy that works for all of us, not just the wealthy few, where all our families and communities can thrive, regardless of the circumstances we’re born into. We, everyday people, are the heroes. Wealthy people and powerful interests who hoard money are the villains. How we get there is by making sure every single one of us can participate, and, when we do that, we all thrive together. When you leave certain people out because of their color or their gender or any other reason, it hurts all of us. Government’s role is to make it possible to stand up for those values. It’s not about whether government is big or small, it’s about who government stands up for: everyday people or the wealthy and the powerful.

This is not complicated. It cuts across all issues.

JB: So, if we have the narrative, and it’s simple and resonates with a majority of people, why is the right-wing neoliberal narrative dominant? Why are we still losing?

RK: The right’s narrative is less and less dominant all the time. And, I don’t think we’re losing anymore. We’ve gone from losing to tying, and hopefully we’ll be winning soon. I’m serious about that.

As a result of COVID you have $600 a week added to unemployment insurance benefits, which ends up being more than a lot of people were making. People love it, and Republicans are freaking out about it, but it passed. We gave checks to almost everybody and we didn’t worry about whether we were making them dependent. We gave loans to businesses if they kept people on payroll. It wasn’t perfect, but the point is it’s contested in ways it’s never been before. I reject the idea that we’re losing right now.

JH: What can we do to get further?

RK: The mainstream Left, the bigger, Washington-focused organizations, are cowed by the fact that we’ve been living in this conservative hegemony. They feel like they have to water down their message and play to the right and left. This is what the pollsters have told them.

I wrote an essay just after Trump’s election called Progressives Should Remember It Is Darkest Just Before the Dawn. I wrote that, as awful as this is, in the long run, Trump’s presidency may be the portal to a new progressive era. Historically, when things have gotten really bad, we’ve had rising movements. We had slavery, and then we had abolition movements. We had Dred Scott, bad as it can get, and we had the Civil War. We had the Gilded Age and the rapacious capitalism of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and we had the Progressive Movement. We had the Great Depression and the New Deal. McCarthyism and the Civil Rights Movement. We’ve now got Trump. Going forward we need more movement and electoral victories, and more conversations about the big programs and bold changes we want. These have started. That’s why I’m encouraged.

I’m not saying that I’m not super anxious: the idea of Trump getting reelected gives me nightmares. But as my first boss, Ralph Nader, said, “Pessimism has no survival value.” Or as Antonio Gramsci said, “Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.”