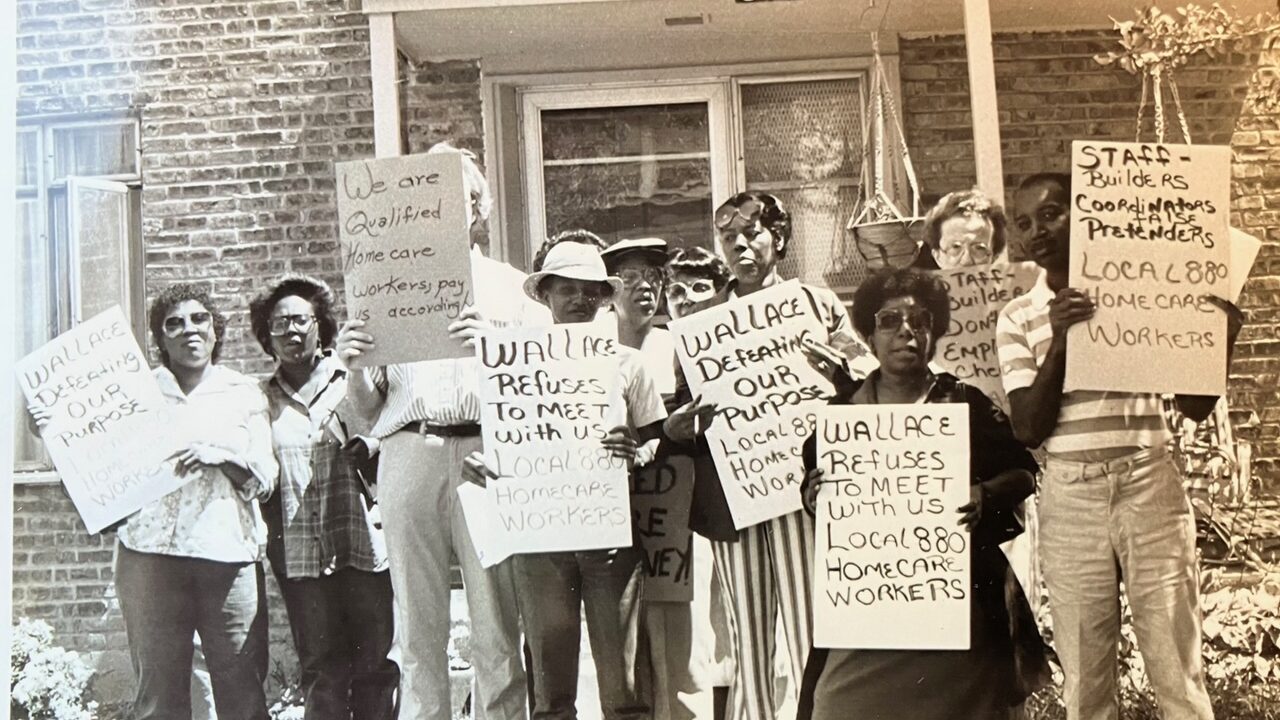

McMaid workers, led by Irma Sherman, Doris Gould, Juanita Hill, and Mary Williamson, transformed labor organizing by successfully unionizing homecare workers in Chicago in 1984, setting the groundwork for the largest union in the Midwest, and catalyzing the organizing of a field predominately staffed by working-class Black and brown women.

In Part One, the McMaid homecare workers, with their union, United Labor Unions Local 880, a small, independent union founded by ACORN, the national community organization, overcame an intense anti-union campaign by management to win a solid union election victory in January, 1984. But even more obstacles lay ahead in their fight for Justice.

As the McMaid workers’ struggle moved deeper into the winter of 1984, the euphoria surrounding the union election in January hit a hard wall of reality: the six-month recognition campaign turned into an additional 18-month fight to secure a first contract, as well as campaigns to organize the rest of the industry, and to raise the poverty level wages and benefits.

Their unique community and labor organizing model –– some organic, some borrowed from ACORN, the UFW, 1199, ULU Local 1475, and other unions –– was developed after years of organizing workers in low-wage industries. They relied on an elected, well-trained, rank-and-file bargaining committee and organizing committee led by Black and brown members –– this may seem like common sense today but at the time went against the predominant labor union orthodoxy where the paid, non-rank-and-file staff bargained the contract with little or no member involvement. Along with this emphasis on rank and file member power was the skilled use of governmental regulatory handles in the political moment and, most importantly, an aggressive direct action plan at and away from the bargaining table.

The ensuing campaign would test the leaders, the members, and the organizers as they fought McMaid’s delaying tactics at then-President Reagan’s Labor Board. They fought the company’s attempts to ignore and walk away from the union, and their attempts to develop their hybrid organizing model to win their first contract while organizing an industry hell-bent on keeping wages low, profits high, and unions out.

Bargaining Committee Elections, Training, Roleplays – Getting Ready for Negotiations

Bargaining committee elections were held at the union hall at one of the regularly scheduled monthly meetings shortly after the initial victory. Some of the original organizing committee members like Irma, Doris, Mary, and Juanita ran for the bargaining committee as did some newer members, like Wilma Murray and her friend Vernell Morris, who had gotten involved during the union election campaign but had not been on the original OC. The committee varied in size from 8 to 15 members, sometimes more, depending on work schedules, since the company refused to pay bargaining committee members for negotiations.

The 880 bylaws, adopted from the United Farmworkers union, stipulated one steward for every 10 workers and strove for similar member-to-bargaining committee member ratios for the committee.

The citywide regular monthly membership meetings kept everyone informed and involved during the contract campaign. At the same citywide meeting, in company breakouts, rank-and-file members from other agencies involved in organizing drives planned their campaigns and provided support to McMaid workers in their fight and vice-versa. Afterward this reliance on citywide cross-agency membership meetings not only built solidarity but set the tone and the action plan for the negotiations ahead.

Bargaining committee trainings were held shortly after the elections in order to get the members on the committee and the members at the monthly meetings ready for what lay ahead. Ground rules were introduced, discussed, and voted on. Scenarios of what might happen at the bargaining table as well as what might need to happen away from the bargaining table were discussed, with an emphasis on keeping everyone who worked at the company informed about negotiations and ready to mobilize in case direct action was needed.

The highlight of the trainings were the roleplays where workers would play the boss and his committee versus their own. They played out various scenarios of what could happen at negotiations and what their responses would be if it became clear that the company’s intentions were really to try and bust the union instead of bargaining in good faith.

The regular newsletter and flyer distributions and mailings –– with articles written by workers –– that were so crucial for communications during the organizing drive were continued throughout the campaign and afterward to keep a solid communication system going.

The Bargaining and Stonewalling Begins – “May a Doorknob hit ya’!”

Negotiations began in the late winter of 1984, several months after company stalling tactics at the NLRB had already failed and Local 880 was certified by the Labor Board. But McMaid hadn’t given up fighting. Instead of bargaining in good faith, as the law required, they chose to spend many months engaged in “surface bargaining.” McMaid would schedule negotiating sessions, make a few word changes in their proposals, make it appear as if they were meeting and negotiating in good faith, but make no substantive offers on wages, benefits, or non-economic changes demanded by the McMaid workers’ committee. With employee turnover approaching 100%, the company was hoping that the workers would give up and walk away.

At one session just before they walked away from negotiations, the company and their high-priced lawyer said they could not afford their moderate proposals, indicated the union no longer represented a majority of the workers, and got up to leave the room. As the acting director of the company walked out and began to close the door, one of the newer bargaining committee members, Vernell, said under her breath but loud enough to be heard: “Well, may a doorknob hit ya’ where the good Lord split ya’!”

The committee members burst into laughter. The acting director came back in the room red-faced, demanding to know what was said, only to be met with closed mouths and stares. The CEO was angry, but speechless. Vernell had said what everyone thought, set the stage for the next phase of the campaign, and magnified the importance of a member-led bargaining committee. After a multi-year fight to win their union and win the right to force their boss to sit down across from them and bargain, they now showed the boss that they had the right to laugh and ridicule him as the boss had just done with to the committee his final offer. The company might have had their fancy lawyers and legalese, but the union had the people and Vernell’s statement said it so well: they were not about to give up after they had come so far.

The Company Walks Away, the Union Pays Them A Visit: “That’s Our Money!”

The company thought they could just walk away, but the workers had other plans.

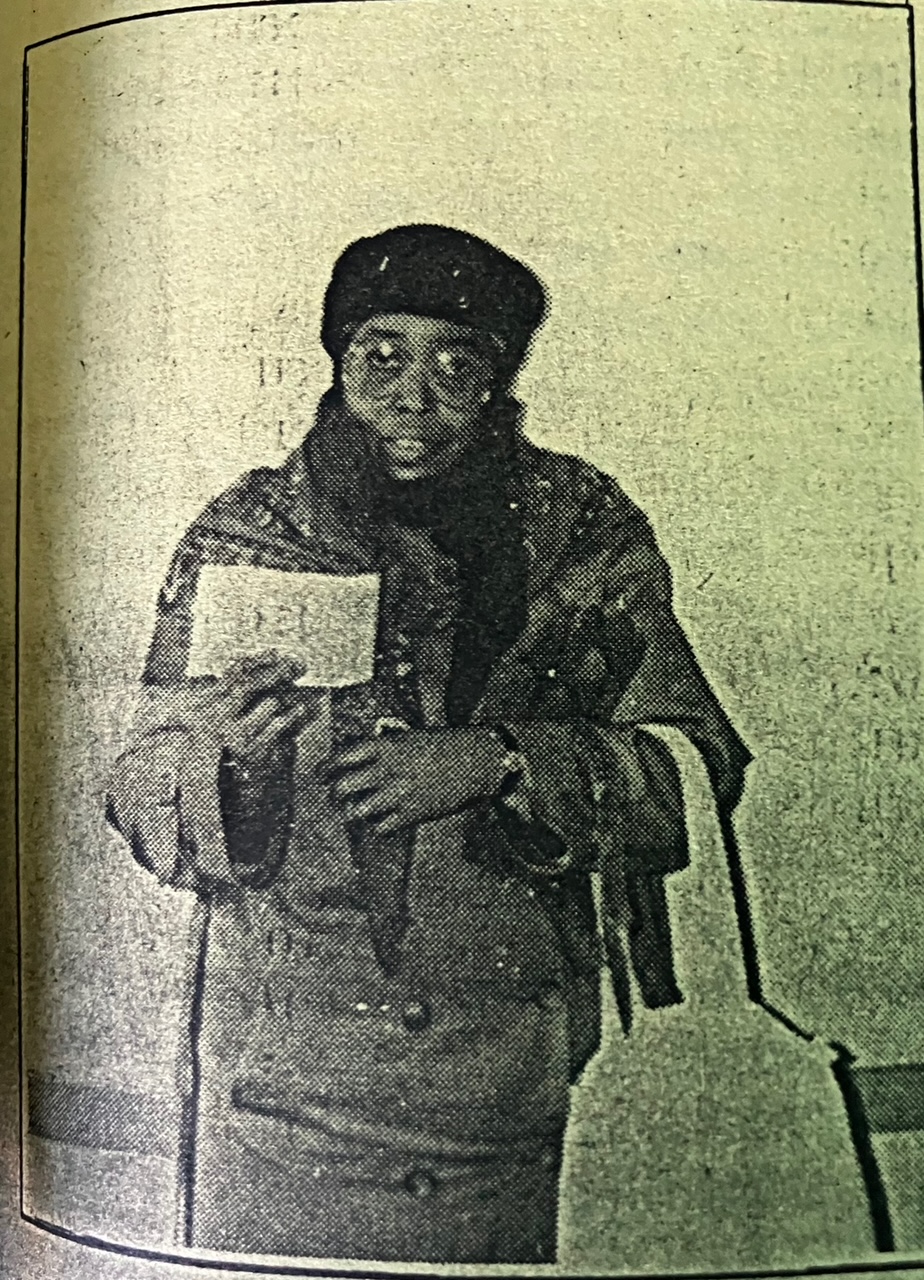

On a cold, gray Saturday in early 1985, Doris, Irma, Mary, and other members of the bargaining and organizing committees loaded into vans and cars and headed to the home of McMaid’s CEO, located 35 miles away in the far northwestern corner of suburban Chicagoland.

As they drove deeper and deeper into the suburbs, a small snowstorm began, but the workers headed towards the CEO’s home undeterred, determined to be heard. They were armed with flyers for the CEO’s neighbors, laying out their grievances with their boss, and boldly listing his home address and phone number and asking that his neighbors call him and tell him to bargain in good faith.

The tour of his community –– the beautiful streets, the expensive homes and automobiles, the enormous wealth –– only heightened the anger members felt for the CEO and his stonewalling, further accenting his life of leisure in suburban opulence while they struggled to survive. They pulled up to his home situated on several acres of land –– with a four-car garage filled with his favorite Jaguar automobiles, his in-ground pool in his backyard, horse stables a little farther back from his home –– prompting McMaid worker Lillie Mae Thomas to shout: “That’s OUR money he’s spending on that house and all those cars!”

They angled into his circular driveway and unloaded, chanting and singing as they marched to his front door demanding in their chants:

“Two, four, six, eight,

McMaid must Negotiate!”

And:

“What Do We Want?

A Contract!

When Do We Want it?

NOW!”

The Police Arrive with a Surprise

Despite the snow and the low temperatures, their spirits were high as they marched up to the boss’s door with a large poster-sized letter, signed by the McMaid members, demanding that he come back to the table and bargain in good faith. They saw the curtains move on the second floor of his mansion, and some thought they saw the boss looking down through his closed linen curtains.

Suddenly, the front door opened and there stood… the boss’s teenage daughter! The workers courteously left their poster letter with her to give to her father, demanding that he bargain in good faith. As she closed the door, members had a good laugh about their boss’s cowardice in sending his young daughter to open the door instead of opening it himself.

As they marched down his driveway to his neighbors’ mailboxes to distribute their flyers, two police cars with sirens blaring and lights revolving zoomed up into his driveway cutting off their path. The officers jumped out of their cars, demanded to know what the workers were doing, read their flyers, coolly reviewed the assembled workers, and announced: “We’re organizing with the Teamsters, too! Have a good day, ladies, and don’t be too long or loud. Good Luck!”

Words of solidarity from the police –– for once! The police then jumped back into their squad cars and drove away, leaving the workers to flyer the neighbors before they loaded up and headed back to Chicago, enjoying many laughs over the day’s events.

The Company Comes Back – Minimum Wage violations and the Workers and Clients Choose

The following week, the company’s attorney called to protest the suburban visit but announced they would be coming back to the table. When they did, several weeks later, they became a little more responsive in negotiations, but refused to move on important demands.

It still took several more months of negotiations and action. Some of the actions revolved around getting the word out about the company’s stalling tactics at the check pickup and in-service trainings where leaders took shifts to talk with workers about the company’s union-busting and asked them to join the union by filling out membership and dues deduction cards before the contract settlement, in preparation for an eventual contract.

They also discovered that the company was refusing to pay workers for the time they were required to travel between two consumers in one day –– legally called “time-in-travel” –– shorting their hours and in effect paying subminimum wage: what today would be called “Wage Theft.” Under federal and state law, if you are required to travel between jobs in your workday, you have to be paid for that time at the minimum wage. In response, workers filled out homemade “time-in-travel forms” estimating their travel time between clients and filed claims with the state and federal departments of labor en masse demanding payment for those lost hours. This turned out to be a blatant form of wage theft with some workers being shorted hundreds of hours of pay per year! The prospect of a major violation of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) and large back-pay judgments and fines also increased the pressure on the company.

They also found that consumers, or clients as the state deemed them, had a right to transfer to another homecare agency under the federal and state regulations of the state’s Community Care Program from whom McMaid and other homecare agencies received their contracts and funding. It is called “client choice” and requires that clients have the right to transfer to another agency for whatever reason, if they are not satisfied with their care. Client choice in effect allows a client, or consumer, the freedom to choose their homecare agency. Since most workers had a very good relationship with their consumers/clients, they were eager to show their solidarity by agreeing to transfer to another agency. Workers and organizers signed up hundreds of consumers demanding to be transferred to other agencies, in effect allowing workers and their consumers to “strike” their company without losing their pay or consumers and transfer en masse to agencies of their choice. The only thing that would change would be the employer’s name on their paycheck. The company and the state both protested this tactic, but the McMaid members held firm, telling both the company and the state of Illinois that it was in the federal regulations and that the consumers and their workers were well within their rights to demand to be transferred to another company.

In June 1985, at the midnight hour, after a last-minute overwhelming “strike vote” and presentation of the hundreds of client choice transfer forms to the company at negotiations, the company agreed to the first union contract by homecare workers in Chicago and Illinois history and, along with ULU Local 1475, among the first in the United States.

Although it was a barebones contract with no raises at first, the workers’ bargaining committee had negotiated important provisions like a grievance procedure, a controversial modified union shop, and a “wage reopener.” The wage reopener guaranteed that anytime the state raised its rates paid to the company, the wage and benefit portion of the contract would automatically reopen and negotiations would begin for higher wages and benefits. The reopener language and another article called an “increased hours roster,” which allowed workers to apply for more hours, were key contract articles pioneered by ULU Local 1475 in their bargaining with their homecare agencies in Boston in the early 1980’s and adopted by the Local 880 committee.

A Contract Victory, But Unhappiness Within the Ranks

But not all were happy. The contract’s modified union shop provision required that current workers did not have to join the union, but all future workers over 30 hours did. Since most workers were under 30 hours, signing up new members might be seen as a challenge, but Irma, Doris, Juanita, Mary, and other member-leaders were out at check pickups and house visiting for weeks to sign folks up. But unfortunately, since most folks were still at or near the minimum wage, they would actually LOSE money when they joined the union, as would Irma, Doris, and the majority of workers in the unit who had already filled out a union membership dues authorization card. The dues of 1% were minimal but still took a bite out of workers’ checks.

To preempt this, they had earlier created the union’s Membership Benefit Plan (MBP) modeled on a similar ACORN and UFW member benefit plan, that was an additional incentive to be a union member. The 880 MBP contained an accidental death/dismemberment plan, discounts on vision and dental checkups and eyeglasses, discounts at local stores, as well as their union membership card, button, and newsletter subscription. Although it was minimal, it was a benefit plan valued by many members who had no benefits at all.

Even with this, some members were frustrated. Mary, an organizing committee member who had attended the first meeting and was a loyal member, was enraged that she was promised she wouldn’t have to pay dues until she received a raise and then was told she would have to pay dues –– without the raises! This led to one angry exchange where Mary spat at the organizer and members who were trying to explain it to her.

However, after many conversations at check pickups, house visits, and membership meetings, most workers understood and saw the union dues as a down payment for future increases. And over a year later, after fierce lobbying and actions by the McMaid workers locally and at the state capitol in Springfield the state raised its rates, the contract reopened, and workers received their first raises in over three years, on top of other improvements.

As for Mary, she came back into the fold and became one of the most loyal members for years after.

Victories Earned, Lessons Learned

The victories earned by the leaders and members of the organizing and bargaining committee – from the first organizing committee meeting in September,1983 through the five months of organizing until the election victory in January, 1984; and the small and large victories along the way to winning their first union contract 18 months later, hold many valuable lessons. Their fusion of community and labor organizing models and tactics into a new model for the emerging low wage homecare industries also provided many valuable lessons for the organizers, members and leaders of the fledgling ULU Local 880. Lessons like the following:

-

Having an elected, trained, and disciplined bargaining committee, combined with an aggressive direct action plan implemented at key points of the negotiation, was fundamental to this victory.

-

Likewise, early discussions of the need for dues, the union’s budget, what the dues paid for, and systemic collection of dues and dues deduction/membership cards, cemented in workers’ minds the importance of dues and took away the company’s most powerful argument against unions.

-

The importance of research by the organizing and bargaining committees, especially with the company’s contracts with the state, and minimum wage law, were all key factors in this contract victory. The pressure points like “client choice” and “time-in-travel” contained in these rules and regulations were major.

-

The targeting of both the company and the state before, during, and after the contract fight, took away the fingerpointing by both and applied the economic and political pressure that eventually led to the settlement.

-

Continuing to organize the rest of the homecare industry citywide during this 18-month campaign, and the solidarity of the citywide meetings and actions kept the workers informed and involved at McMaid as well as other agencies.

-

The contract language and support from the Boston local to get through the bargaining obstacles around wages, hours, and benefits, that would otherwise have been insurmountable was also key to the settlement.

-

The decision by the leadership and committee to accept a contract with NO initial wage increases, after fighting for almost two years sealed the victory and allowed the workers to survive to fight another day. This would not have been possible without the leadership training on the front end of the drive and later in bargaining committee training.

-

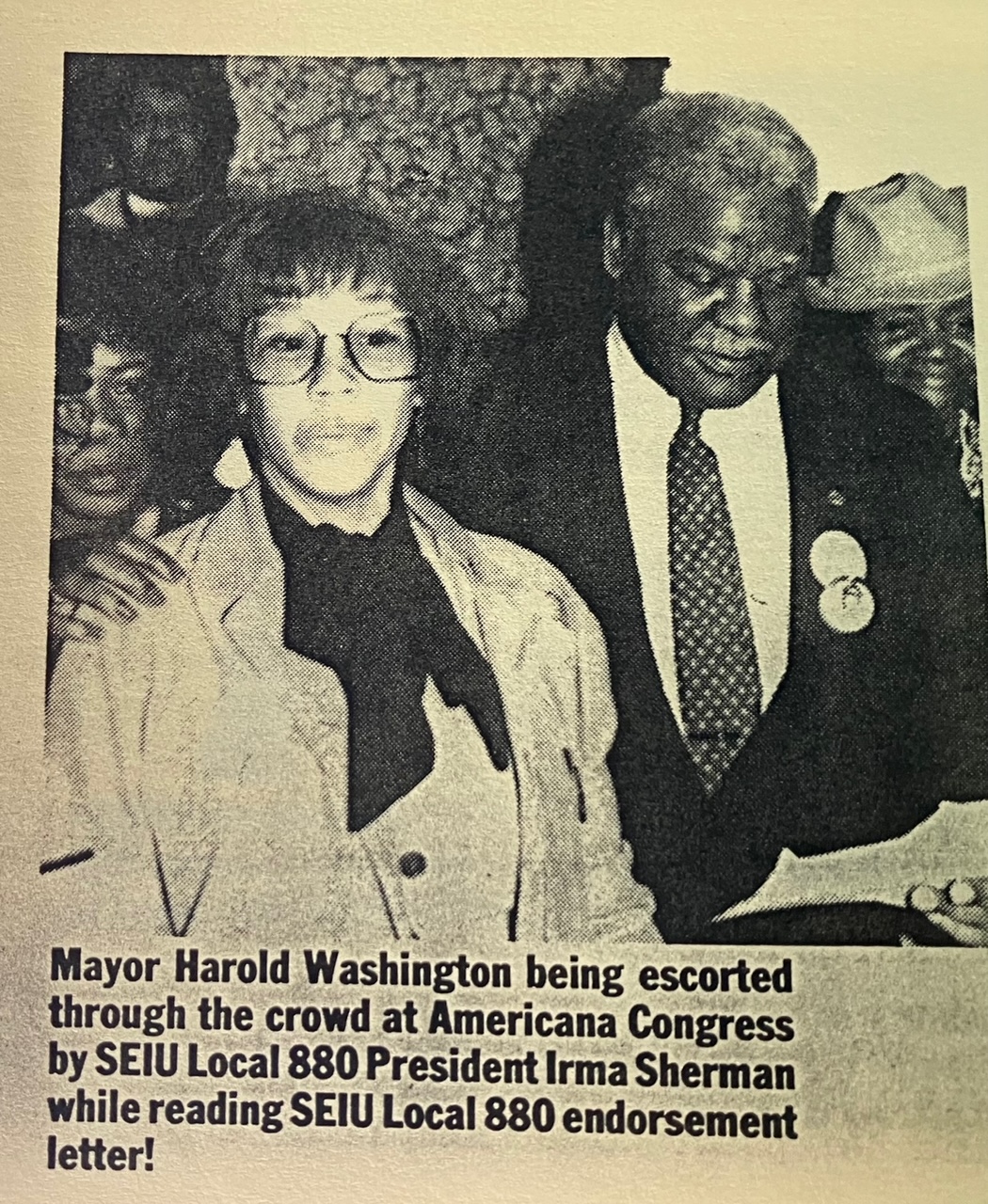

It is also important to note that the political climate surrounding the drive –– most key, the election of Harold Washington as Mayor in 1983 and 1987, his victory over the white Democratic machine, and the ascendancy of Black and brown people in Chicago politics, heightened the expectations of Black and brown people across the city. Securing a signed letter of support from Harold Washington to homecare workers’ organizing and his attendance at several get-out-the-vote rallies during our later organizing only added to this excitement for change for homecare workers down the road.

From 7 members to 70,000

During and after that multiyear McMaid campaign, Local 880 went on to organize a majority of the remaining private and public sector homecare ––– and later childcare ––- agencies in Illinois and in the process organized the largest union local in the city of Chicago, the state of Illinois, and the Midwest, growing from only 7 members in 1983 to over 70,000 members by 2008.

McMaid changed its name in the middle of the organizing drive and is today known as Addus Health Systems and 880 eventually won a statewide and later national neutrality agreement with the company –– today, over 14,000 Addus homecare workers are union members.

SEIU today represents over 750,000 homecare and childcare workers among its 2 million members.

The homecare workers today average $17.25 and have won paid healthcare coverage, paid holidays, paid vacations, pandemic pay, paid trainings, and many other benefits. In addition, after many actions and anti-wage theft campaigns resulting in large backpay settlements, workers are reimbursed for their time-in-travel as well as their cost of travel.

They are currently fighting for a new contract that will raise wages toward their $20-$25/hr goal, greatly improve benefits, and win a path towards retirement coverage. Still too low, but closer to a living wage.

SEIU Healthcare, Illinois, Indiana, Missouri and Kansas (HCIIMK), Local 880’s successor local, is the largest union of any union in the Midwest, representing over 90,000 workers providing vital homecare, childcare, and healthcare to hundreds of thousands of people across Illinois and the Midwest every day. One of the largest Black-led locals of majority Black and brown workers in the country.

HCII’s training arm, the Helen Miller Education and Training Center (HMETC), trains tens of thousands of homecare and childcare providers every year.

But the real heroes in this campaign were Irma Sherman, Doris Gould, Juanita Hill, Mary Williamson, and the many others who took the risks and dared to organize their union 40 years ago.