This is a republish of part of a series of CCI substack posts and a policy brief exploring why the United States needs a Green Industrial Policy for Housing.

The United States is in the midst of a decades-long housing crisis that has metastasized to touch every part of the country and reach into households across the income distribution. This is impacting workers from coast to coast as the cost of housing outpaces wages (on average, workers where I live in California need to make $50 an hour to afford to rent a 2-bedroom apartment).

The housing crisis is not only affecting workers’ rents and mortgages, but also the availability and quality of their jobs. The Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007/2008 expanded the housing crisis’ reach as widespread foreclosures destabilized communities while the addition of new supply slowed to a trickle with the collapse of the homebuilding sector. Even as the economy recovered, the sector did not keep pace with demand; total approvals did not reach pre-GFC levels until after the post-pandemic recovery, even as starts remained about 35% lower. As housing supply has dwindled, so too did residential construction jobs, which remained below their pre-GFC peak at the end of 2024 .

Map by NLIHC

There is a broad coalition cohering around the shared and important goal of increasing housing supply. But in some portions of that coalition, unionized labor is pitted against housing supply goals. Recent frameworks like Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s “Abundance Agenda” put new terminology on familiar “Yes in My Backyard” approaches. Leaders of this movement have voiced scepticism of labor standards, routinely prioritize deregulation to workers’ rights or working conditions, and have even spearheaded legislative efforts toweaken labor standards in California or veto significant labor advancements in Colorado. They also often aim to unleash further unregulated private market activity –– the same types of predatory financialized housing that have impacted workers for decades.

Workers have a crucial role to play and a deep self-interest in a robust housing supply agenda, but the liberal housing supply solutions don’t fully give labor a seat at the table.

As a result, labor unionists like me are turning to another solution: high road social housing, in which we increase public sector capacity to fund and build new affordable housing and create thousands of good paying, high quality jobs in the process.

Social Housing on the High Road

High road standards are a suite of policy approaches and labor standards ‘aimed at creating “good jobs” characterized by family-sustaining, living wages, comprehensive benefits, and opportunity for career advancement.’ In the construction industry, the “high road” is synonymous with union signatory contractors who compete on the basis of the quality and efficiency of their services, participate in joint labor-management run apprenticeship programs, and emphasize safe jobsites.

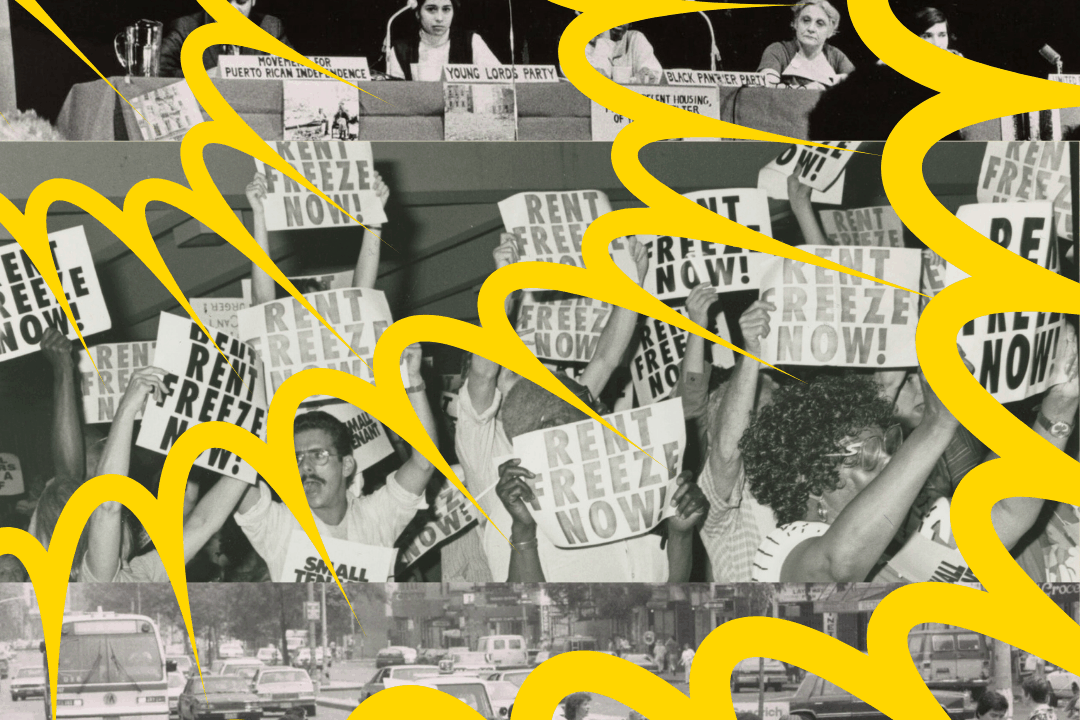

In building the social housing coalition, housing advocates are harkening back to Catherine Bauer Wurster’s efforts 90 years ago articulating how the housing production system neither builds housing the majority of workers can afford nor employs workers at sufficient wages to afford the housing it builds. While the issues facing America’s workers are nowhere as catastrophic as during the depths of the Great Depression, the problems are nonetheless serious and spurring labor to action.

Labor has generally been supportive of funding affordable housing through bond and tax measures to support projects built via the Low Income Housing Tax Credit model but current conditions and the inadequacy of what has become the traditional LIHTC approach are leading some unions to look at alternatives. These alternatives are all the more important as affordable housing funding dries up and displacement of working class households –– especially those in the public sector –– weakens the political power of organized labor. Labor’s interest in social housing is showing up all over the country and reflective of the housing crisis’s reach.

In California, we are building new coalitions for social housing on the high road

California, where I work and arguably the epicenter of the nation’s current housing crisis, has long been a national policy leader and organized labor is pursuing legislation to enable social housing programs as the need for permanent affordable housing resonates widely within the labor movement. Local campaigns have been at the forefront of this organizing due to growing pressure from rank and file union members and a broader recognition by some union leadership about the dilution of political power as fewer members are voters in the places where they work. San Francisco and Los Angeles have led the way as state-level efforts have steadily advanced.

In 2020, San Francisco, a coalition of San Francisco Board Supervisors, public employee unions, and housing organizers successfully campaigned for a real estate transfer tax local ballot measure and an accompanying “Housing Stability Fund” with an oversight board to provide a revenue source for eviction protections and other affordable housing programs for San Francisco. Following that win, the San Francisco Central Labor Council, Council of Community Housing Organizations, and the Jobs With Justice community-labor alliance collaborated on a report, Housing Our Workers, that showed pervasive housing insecurity among San Francisco’s public employees, placing workers at the center of investment demands. Although the SF Building Trades and a number of its affiliates opposed the transfer tax when it appeared on the ballot due to concerns about impact on Union pension fund investments, Rudy Gonzalez, Secretary-Treasurer of the San Francisco Building and Construction Trades Council (SF Trades) has been clear-eyed about the need to have the Trades as part of the social housing coalition and in 2024 worked with the SF Board of Supervisors to amend the transfer tax to exempt the first sale of Union pension-financed multifamily projects with on-site affordable housing. The Housing Stability Fund Oversight Board (HSFOB), on which I serve on behalf of the SF Trades, has sought to direct the more than $400 million in collected revenues towards both immediate issues such as eviction protections and capital improvements for senior accessibility, as well as long term issues like a social housing feasibility study, land acquisition, and early stage funding for projects to serve educators. SEIU members in particular actively participated in the development of the HSFOB’s recommendations through their passionate testimony about growing and unsustainable commutes, implications for service delivery (particularly during emergencies), and their desire to return to the communities from which they were economically displaced. In addition to their activism in support of social housing efforts in San Francisco, the work of rank and file members has resulted in SEIU incorporating housing demands as part of their collective bargaining campaigns.

Los Angeles has also waded into the social housing space through the United to House LA (ULA) “Mansion Tax” campaign. Funded by special real property transfer tax on conveyances of real property over $5 million, the measure has generated over $400 million dollars since going into effect in April 2023 after withstanding legal challenges. Similar to San Francisco’s measure, ULA is intended to fund new affordable housing production; eviction prevention and defense work; an income assistance program to provide direct cash payments for seniors, Angelenos with disabilities, and other at-risk renters; and a Social Housing and Alternative Models Program to develop new and innovative housing solutions focused on permanent affordability. According to Chris Hannan, who ran the LA-Orange County Building Trades at the time and is now the Executive Secretary of the State Building Trades Council, the ULA coalition had Labor at its core from the beginning with the Trades and UNITE-HERE. Building Trades funds and union boots on the ground helped get the measure on the ballot and underwrite the campaign. The measure also came out of earlier successful collaborations to win affordable and supportive housing and transit funding measures that have provided material benefits to LA’s construction trades. Moreover, those efforts demonstrated to community members how involving the Trades could provide added community benefits through Project Labor Agreements that established and exceeded local hiring and apprenticeship goals throughout program implementation with no measurable cost impact.

At the state level in the California Legislature, proposed social housing legislation has taken different approaches and garnered varying forms of labor support. The primary legislative win for the social housing movement at the state level was SB 555, which enshrined a definition of social housing in State law and funded a feasibility study for statewide a social housing program; the study is currently in progress. Arguably the most expansive bill to decommodify housing that the state has seen in recent years is SB 584, which was sponsored by the Building Trades but died in the Assembly after passing the Senate in 2023. The bill would have established a “Laborforce Housing Fund” via a statewide assessment on the commercial use of residential homes and apartments for short-term vacation rentals (i.e. Airbnb) to finance projects by “public entities, local housing authorities, and mission-driven nonprofit housing providers.” It included strong labor standards, was consistent with the goals of SB 555, and won the support of the state’s housing justice movement. Unsurprisingly it was opposed strongly by Airbnb, Realtors, some tourism associations, and business groups like the Chamber of Commerce, Bay Area Council, and Silicon Valley Leadership Group.

A nationwide movement

Beyond California, efforts elsewhere in the country show the growing momentum from labor in support of high road social housing. In Seattle, veteran labor organizers supported the winning push for a green social housing ballot measure because they were interested in its potential to prevent the displacement of working people out of the city and to arrest the dilution of the Labor vote there. In Rhode Island a coalition of housing justice and labor groups led by ReclaimRI and the International Union of Painters and Allied Trades (IUPAT) have been steadily building support for a public developer to help address the small state’s burgeoning housing crisis, strengthening links to labor through tenant organizing and rent stabilization campaigns with SEIU 1199NE (health care), AFT (teachers), UFCW (food & grocery), and UNITE-HERE (hospitality). In New York State, legislation has been introduced in both the Assembly and Senate to create a public developer with the support of the Building Trades Council, Carpenters, and teachers unions. The New England Housing Initiative has been formed to support labor union-led efforts to address the affordable housing crisis and homelessness with an advisory board made up of state labor and building trades councils, tenant organizers, and immigrant rights advocates. And other efforts in Washington DC by Green New Deal advocates and in Oregon by the state’s affordable housing consortium are continuing to build support across the political spectrum.

Parts of organized labor have often been a reliable partner in affordable housing campaigns but the current confluence of housing availability, cost of living, and climate crises has led to deeper coalitions. Pressure from rank and file members experiencing housing insecurity, as well as from leadership seeing erosion of political power in unionized areas where members are unable to live near work and the continued reluctance of developers to employ skilled, trained, and fairly compensated construction workers who can afford what they’re building have all combined to concentrate attention and create openings for innovative collaborations.

The movement for a new approach to addressing the nation’s affordable housing needs is still young, but the confluence of interests between organized labor, housing justice advocates, and affordable housing developers seeing the limits of the current system is only growing stronger. Together they will put housing on the high road.