One of the most significant and damaging achievements of the neoliberal narrative is that the vast majority of people in the United States believe, in the words of Margaret Thatcher, “There is no alternative.” The fear that nothing can change has a de-politicizing effect. As the director of the community organizing groups ISAIAH and Faith in Minnesota, Doran Schrantz has made it her goal to challenge that idea. Her organizations are vehicles for people to reclaim their agency and act collectively to build a shared future.

Doran talked with us about how organizers can create spaces for politicization. It starts with confronting the effects of white supremacy, patriarchy, and class exploitation on their own lives, and then transforming that story from an experience of private pain into a call for public accountability. The process of moving from individual shame to collective responsibility is an essential building block of organizing.

In 2018, in collaboration with Anat Shenker-Osorio, Faith In Minnesota and partner organizations used that strategy as a starting point for a scaled political communications strategy (#GreaterThanFear), which helped to change the political landscape in Minnesota. Fifteen organizations joined the open-source communications campaign, which was designed to dampen racial polarization, push back against racist and Islamophobic scapegoating, and create a more inclusive, welcoming political environment for the 2018 midterm elections. The hashtag, memes, and videos went viral and contributed to the Democratic-Farmer-Labor win at the State House and progressive victories up and down the ballot. Today, Faith in Minnesota is collaborating with a set of partners to build public support for essential workers and caregivers (#WhoCaresForUs). These narrative campaigns are setting the stage for policy campaigns on important structural issues like raising revenue to invest in the safety net, early learning, and community schools.

In Doran’s view, the future is open. The challenge for organizers is to transform the public conversation and invite people to take action to create a better future. If we fail, right-wing populism will take advantage of our hopelessness and despair. If we succeed, the future is ours to create. This interview, which has been edited and condensed, was recorded before the recent uprisings against police violence.

Jonathan Heller: We’re in the midst of the Covid 19 pandemic. What do you see as the potential direction the country could go in as a result? Is it a time where we might see positive changes?

Doran Schrantz: I’m not a fortune teller, so I won’t make predictions, but I’ve been thinking a lot about this moment and how it is all contingent.

Forecasting, informed predictions, opinion polling, and analytics may suggest the future that lies ahead of us, for good or bad, but these prognostications only point to possible pathways. If we assume the future is beyond our control, that things are inevitable, then we are vulnerable to despair — which is a fertile breeding ground for right-wing populism and “opt-out” alienation. But if we take responsibility for what happens and reject the idea that we are merely consumers, spectators, or passive bystanders, then we can recognize we have the collective agency to imagine and create the future. We can reclaim our role as active creators of the public world in which we live.

In the last couple of years, ISAIAH and other Midwestern organizations have conducted a round of public opinion research connected to the Race Class Narrative. We’ve been talking to people (Black, Latinx, Native, and white) in the postindustrial, northern midwestern landscape. One of the insights that came out of the research is that people lack a sense of a future. They aren’t oriented to the idea of having a future, or what that future is, or how to create it. This makes some white people open to a retrograde orientation that urges an illusory “return to the past,” such as “Make America Great Again,” where an “other” (Black, immigrant of color, Muslim, etcetera) is the scapegoat. Many other people, including those in our core base, can have a passive, fatalistic sense that the future is doomed to be the same or worse, and out of their control. Given the last thirty years of neoliberal economic policy, which is supported and kept in place by entrenched structural racism, it is rational for people to come to the conclusion that politics doesn’t work and that individual survival is the only goal to shoot for. “Has my life changed? Do I think it will ever change?” This is political failure, and the cost is a loss of the belief that we make our future and that politics and public life is how we change the present and create the future. And this loss is a big factor in making the Midwest such fertile ground for right-wing populism, white nationalism, and ethno-nationalism, which is how Trump squeaked out a win in 2016.

Trump animated white people’s existing racism, but that isn’t the only dimension of what happened. It was also anti-politics: people’s inability to feel a sense of agency or imagine they can create a worthwhile future for themselves. Politics becomes a set of meaningless signifiers that we are invited to consume. For example, “Build the Wall.” No one thought he would actually build a wall that Mexico paid for and no one thought he would actually deport eleven million people. Those are just empty signifiers that cruelly terrorize people. In practice, these politics devolves to mean and inhumane gestures, like caging immigrant families at the border. This practice is obviously traumatizing to real human beings, but, at the same time, is completely illogical, incoherent as policy. It’s not meant as policy, it’s meant to signify to the base and feed the nihilism.

The stakes are hugely high in 2020. We can run political campaigns and organize, but if we don’t take responsibility for creating a sense of the future, a story of a shared future grounded in concrete solutions, then our work could actually accelerate the crisis we’re in. This pandemic and the failed government response to it could feed right-wing populism.

JH: As you help create a sense of agency and help people imagine a future, is it important to have a narrative strategy?

DS: Yes. Narrative strategy is very important, but it’s not just going to be something we say; it’s also something we do. You have to show, not tell. You actually have to live that out in the life of your organization. Is that actually the DNA of your organizing? ISAIAH and Faith in Minnesota set out explicitly to build people’s sense of agency. We try to build political spaces in which people can transform their sense of themselves as political or public actors. The North Star of our organizing is our ability to offer people a sense of their own power and agency and develop our collective capacity to build a path to power together. This mission infuses everything we do.

Judith Barish: It seems like it could be hard to show people they have agency. That’s almost a contradiction in terms. What does leadership development look like for you?

DS: We use this phrase “crossing the bridge” a lot. It is shorthand for the process of a person transforming their experiences of powerlessness into a path to public power and leadership. This bridge crossing is only something we can do together, in a political community, and we do it committed to our mission of making multi-racial democracy a reality. One part of it is learning to tell our own stories grounded in a political analysis. For example, our annual weeklong grassroots leadership training (about 120-130 people attend annually) leads participants through a set of conversations and presentations that explore the interlocking structures of hyper-capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy. We make sure people understand that none of these systems exist without powerful people and powerful institutions. The exploitation of workers, the systematic deportation of immigrants, and the mass incarceration of Black people are not part of the “natural” order, and none of it is inevitable. People designed them and people benefit from them. Most of us, however, are neither the designers nor the beneficiaries. Those of us in the 99% are differentiated by race, class, gender, geography, and other factors, so we are differently positioned in the stratified hierarchy of racialized neoliberal capitalism, but almost all of us experience pain and hardship from our experiences of powerlessness as a result of the dominant social structures.

At ISAIAH, we believe the path to overcoming this system is to build agency, multi-racial solidarity, and a path to collective power. For example, we invite people to tell a story about how racism or patriarchy impacted them personally, and usually two organizers or experienced leaders model it first. Last year Brian Fullman, a Black, formerly incarcerated barber who’s now a lead organizer, and Laura Johnson, a white working-class woman from Brooklyn Park who is also an organizer, told their stories. Both took full responsibility for their own life narratives. They didn’t hide or perform. Then people work on moving their story from private to public and simply share. This can create moments where, in one session, a white man from the suburbs recounted, “I’m in deep debt, and I can’t tell my wife, and I was suicidal because I thought it was all on me.” And, then, a Black man said “I never trusted white men. I don’t know if I should, but it helps to know you, a white guy, are going through that.” As an organization, we recognize that what you experience “counts,” whether you are Black or white, identify as male or female or non-binary. We are situated differently and impacted differently, but we are all impacted and we all have a public interest in changing the structures. That’s the building block of solidarity. Not “allyship,” but solidarity. This exercise probably teaches more about neoliberalism and capitalism and white supremacy than any book ever could.

There are few spaces in our society where we learn to participate in a multiracial democracy — because America hasn’t achieved this yet. White supremacy and patriarchy and neoliberalism have effectively divided us from each other and eliminated public spaces where this kind of political community could emerge. Organizations have to carve out the space and protect it. This is how we learn and are formed to be citizens and practitioners of a multiracial democracy.

JH: A lot of this leadership development work happens one person at a time. How do you take it to scale?

DH: Particularly in a time of disinformation and historic mistrust of institutions, I believe it’s regular people talking to people they know in the context of dense social networks that has the most potential to influence someone’s decision to vote or to shape their view on a policy. But in this public moment, when we want to influence the public environment and shape public discourse, we have to build a different kind of narrative architecture to do that work. And, even in larger, “scaled” creative content like ads, videos, or social media content, we have to be asking harder questions about what we are teaching and inviting from the “audience” we are building. Even when we are talking to millions of people, not just a few thousand, we are responsible for creating the conditions for democratic power building — creating an alternative to the doom cycle, individualism, and politics as something we consume.

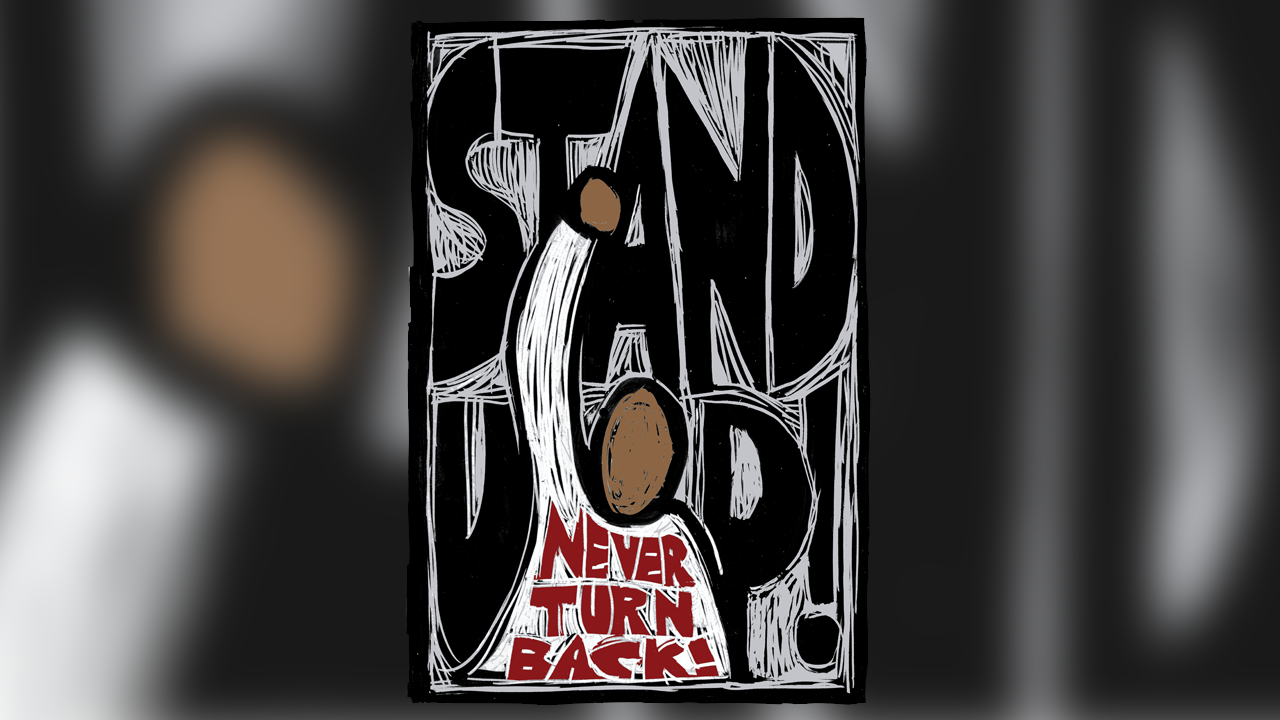

A narrative strategy isn’t just a set of messages or a set of abstract concepts, it’s also demonstrating how we are in relationship with one another. It has to communicate a powerful role for people in public life, build solidarity, and challenge people to take a risk and take action with others. We try to show people taking on responsibility for their actions — being the protagonist in the play. It’s also important to invite the audience to get on stage and become protagonists too, rather than casting them as spectators or consumers. We must make everything we’re doing publicly an invitation to take action and become a protagonist.

Here is a bad example. Recently, ISAIAH filmed a set of video testimonials for social media, just as the pandemic was unfolding. Our intention was to shine a light on essential workers, taking advantage of a moment where childcare workers, teachers, grocery store workers, and healthcare workers (most of them women, Black, and/or people of color) are visible as the backbone of our economy. Unfortunately, the implicit editorial point of view of the videos was, unintentionally, an invitation to the audience to “feel sorry for these poor people.” Instead of creating a sense of “we” — I relate to that woman, I can identify with her challenges, what can we do together? — these videos called the viewer to believe that their role was to experience pity which, in turn, made them feel, perhaps, superior and virtuous. It was not about solidarity. It did not build a “we.” It was, in fact, unintentionally otherizing. We did not release these videos. We redid our campaign to make the storytellers people who are agents and challenging others to become agents with them.

JB: Can you tell us about some scaled efforts to change the public narrative?

DS: Community organizers typically do our work one person at a time, with in-depth conversations that take place in shared physical space. So we face a distinct communications challenge as we figure out how to engage a wider audience. What kind of architecture can allow us to reach two million people? In Minnesota, community-based organizations piloted a scaled political communications strategy in our 2018 #GreaterThanFear campaign. The problem this campaign was trying to solve was how to both inspire and motivate the emergent, multi-racial, progressive electorate in Minnesota while also neutralizing the weaponized, racialized, white grievance politics with persuadable whites. In the short term, we wanted to win a set of state-wide races, and, in the long term, we wanted to grow the potential for a multi-racial, rural/urban, multi-generational progressive governing majority.

This had two critical components. First, we created an “authentic messenger” program that was to be our foundation for persuasion and inoculation. Our theory was that the most persuasive spokespeople are people you already know and trust. So we invited our grassroots community members to become public messengers. We trained clergy, people of faith, childcare providers, barbers, and other community leaders to use their influence with friends and family. For example, Mohammad Omar of our Muslim Coalition is a powerful influencer in the Somali community in Minnesota, though no one knows his name unless they are part of that community. He is one of the most critical messengers to shape a story about Muslims claiming their voices. Or Jessica. She is the right messenger for other small town and rural folks in her community — she knows everyone, and her selfie video will be much more effective than a polished actor in a fancy ad. We built an infrastructure to help community influencers build and reach their own audiences with stories, videos, etcetera.

The second thing we did was build a hub to support similar activities for dozens of membership-based social movement organizations. We agreed to share resources, digital, communications material, and staff capacities. The core was Education Minnesota, SEIU, Faith in Minnesota, Land Stewardship Project, TakeAction Minnesota, and Unidos Minnesota — but over 22 organizations participated. We also aligned with the Minnesota Values Project, a group of legislators who are building support for a shared political agenda. These allies have maintained their distinct voices, but we all contribute to an echo chamber effect. When enough people and organizations use similar, reinforcing messages in their own spheres of influence, we can move a narrative at scale.

Around this core architecture of networked community influencers grounded in communities, we built the Greater Than Fear campaign. This was a branded campaign with a nice ad, paid digital, paid radio, a messaging guide, paid canvassers, etcetera. This created a surround sound effect that made the local, community-based, authentically rooted work more effective and “sticky.” But the “scaled” communications worked best not as the centerpiece, but as what surrounded the work of people talking to people, people doing earned media, op-eds, selfie videos, and community conversations.

JB: Where does neoliberalism come in?

DH: The neoliberal worldview and power structures constrict public life. They choke off a sense of collective responsibility and promote an individualized, consumer orientation. They put the blame for economic hardship on the people who are suffering, so people feel shame for the challenges and powerlessness they experience. As organizers, we witness the impact of individualized shame every single day: we have to pull people out of that self-blame to awaken an idea of themselves as a public person, full of potential, a creator.

Neoliberalism destroys public goods. It sells off, privatizes our collective assets, including schools, parks, and hospitals. At ISAIAH and Faith in Minnesota, our major structural response is to expand the public, both public accountability and public ownership. But to do that, we have to build a new kind of politics. We have to expand the electorate and pass policies that can increase public ownership, democratize wealth, and relentlessly grow democratic power. In the fight over the levers of government, we have to build power: the power to enforce laws, claw back the commons, and carve out a new imagination about the public good. And to fight for a more democratic rather than technocratic, merely liberal orientation toward politics.

JH: What do you think of the narrative that we all create the wealth of society together, so it actually belongs to all of us, not just the CEOs of large corporations, and we should all have a say in what to do with it?

DS: That narrative is part of the story we need to tell. It articulates the idea of reclaiming the public. It is a critical part of the strategy to shift elite opinion making, though it is probably not the way we would talk to regular grassroots people. When we argue for progressive priorities, we’re up against a huge infrastructure that supports neoliberalism amongst elites: the Brookings Institution, the Aspen Institute, Davos, the economics departments of major colleges and universities. If you break too far from this drumbeat of consensus and opinion, your voice is marginalized completely. So we need to engage those elite vehicles of opinion.

In Minnesota, for example, we want to build a campaign that could raise five billion dollars through taxes on corporations and high earners to design democratic public programs and institutions that benefit working people: full-service community schools, public community-based childcare centers, a complete overhaul of homecare and healthcare for seniors, paid time to care, divesting from incarceration/surveillance, an immigrants’ bill of rights, including access to public benefits, and investing in community violence prevention, etcetera. To accomplish that, we need an elite campaign aligned with a broad-based, grassroots organizing campaign to align credible messengers and shift elite opinion. We need to expand the imagination of public officials to fight for bigger things, and give them arguments and evidence to support those positions. I imagine an interconnected set of universities, professors, think tanks, legal opinions, memos, briefings for lawmakers and the governor, panelists, editorialists, and so on. Our challenge: construct an alternative to neoliberalism with its own ideas, its own trajectory, its own policy, and its own deep powerful thinking.

JH: Do you have any other thoughts you’d like to share with us?

DS: The future has never been set in stone, but in the era of COVID-19, it feels more open, contingent, and undetermined than ever. And this uncertainty creates an opportunity for democratic action to shape the future of Minnesota and the country. The crisis could shake people out of their passive roles as consumers and observers and invite them to claim their own agency and power, as active participants in public life and democratic architects of the world to come.

If we succeed, and our social movements construct a politics that excites people’s imagination, asks them to imagine what could be possible, and invites them to stand at the center of that possibility, the sky’s the limit. In the seventeen years I’ve been organizing, the public agenda has changed dramatically. Significantly more is possible today than twenty years ago. Today, we are in a position to expand political participation and widen public space.