This article is part of Countervailing Power, a joint series by The American Prospect and The Forge that explores the ways organizers can use public policy to build mass membership organizations to countervail oligarchic power. The series was developed in collaboration with the Working Families Party, the Action Lab, and Social and Economic Justice Leaders.

In March 1975, I took a job as chief investigator of the Senate Banking Committee. My boss, Sen. William Proxmire of Wisconsin, had just become chairman, and he was looking for a journalist with a financial and investigative background to fill the newly created post.

Proxmire had been the very effective chair of the Subcommittee on Consumer Affairs. He was the nemesis of the banking industry. He had successfully sponsored Truth in Lending, Fair Credit Reporting, and Equal Credit Opportunity legislation. After the 1974 election, the banking lobby did everything they could to block Proxmire, now the senior Democrat on the committee, from ascending to chair, but they failed.

When I reported for work, my immediate boss, committee staff director Ken McLean, handed me a thick folder titled “Redlining.” A week later, we had a meeting with more than a dozen leaders of community groups from around the country. They were among the best organized and most strategically savvy activists I’d ever met.

They told us the story of local banks taking deposits from racially changing or heavily African American city neighborhoods but refusing to extend mortgage credit there. This form of redlining played into the hands of real estate “blockbusters” who profited by stampeding whites into panic-selling to brokers at fire sale prices. The brokers then sold the homes to Black buyers at exorbitant markups, and arranged inferior and risky forms of financing.

This created a self-fulfilling prophecy of neighborhood resegregation. The community groups, which included white, Black, and Latino members, believed that if credit flows to redlined neighborhoods could be normalized, then integrated working-class neighborhoods might survive, blockbusters could be defeated, and property values would hold up.

It was a subtle, elegant, and idealistic insight. And they had a strategy to go with it. They targeted offending local banks and showered them with bad publicity. But what they needed was better data.

For now, the only way they could demonstrate patterns of redlining was to go to the local recorder of deeds and look up mortgage transactions, one at a time. This was hugely time-consuming, though it did produce some damning reports in cities from Chicago and Toledo to St. Louis, Washington, D.C., and Boston.

The groups wanted legislation requiring banks to disclose the geographical pattern of their deposits and loans, by ZIP code or ideally by census tract. They then could readily document and publicize patterns.

I wish I could take credit for what became the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act of 1975 (HMDA) and the more far-reaching Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 (CRA), but the idea came entirely from the community groups. After the meeting, Ken and I pitched the concept to Proxmire. He loved it.

Prox was a rare bird: a tight-money progressive. He didn’t like deficit spending or wasteful public outlays. He famously sponsored a Golden Fleece Award making fun of dumb government projects. But he loved regulatory uses of government such as the Truth in Lending Act. What became the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act was perfect. It didn’t cost the government a penny, and it deputized community activists in a quasi-regulatory role of monitoring banks.

Proxmire authorized me to schedule four days of hearings for HMDA the first week in May. Opening the hearing and welcoming community witnesses, Proxmire declared: “Banks welcome their business at the deposit window, but when it comes time for the dream of homeownership,” urban savers “find that they live on the wrong side of the tracks.”

At the hearings, leaders of community groups such as the East Oakland Housing Committee, the Cincinnati Coalition of Neighborhoods, the Jamaica Plain Community Council in Boston, and several more presented documented findings of pervasive redlining. Joining them in support of the legislation was an impressive array of civil rights leaders, including Clarence Mitchell of the NAACP and Ron Brown, then of the Urban League, as well as Gov. Dan Walker of Illinois and Ken Gibson, the mayor of Newark, on behalf of the U.S. Conference of Mayors.

We cast several bankers, savings and loan executives, and trade association officials in the role of stock villains. They testified against the bill, warning darkly about the risks of federally mandated “credit allocation.” The Ford administration also testified against, as did the Federal Reserve.

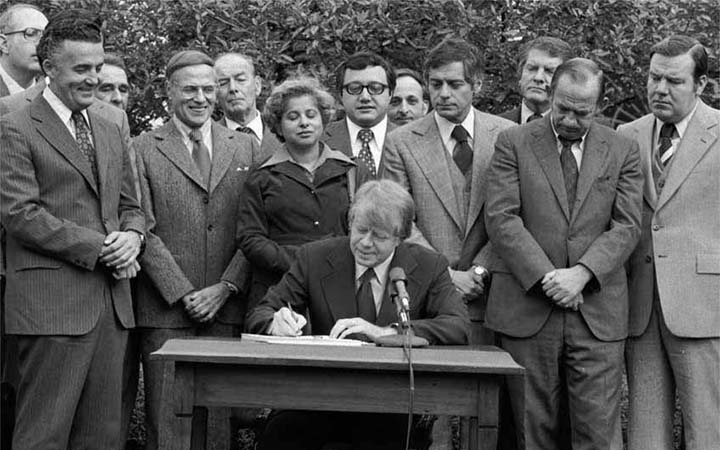

But Proxmire had a working majority on the Banking Committee. So we managed to get HMDA out of committee and onto the Senate floor, where it passed by two votes. It also barely passed the House, and President Ford signed it.

Now there was a powerful grassroots coalition armed with a more potent organizing tool. Meeting with community leaders in 1976, we decided to take the next logical step and create not just a mandate to disclose but an affirmative obligation to lend in redlined areas. That became the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977.

THE REINVESTMENT MOVEMENT WAS SPEARHEADED by three national groups and some inspired local leaders. In Chicago, a stay-at-home mother of six named Gale Cincotta lived in the Austin neighborhood on Chicago’s West Side, a prime target of blockbusters. In the late 1960s, Cincotta, the daughter of Italian and Greek immigrants, organized the Organization for a Better Austin (OBA) to resist blockbusters and press for normal bank credit; then in 1972, she created National People’s Action on Housing, later renamed National People’s Action and finally just People’s Action.

Cincotta connected with a Saul Alinsky–trained organizer named Shel Trapp. Their strategy was classic Alinsky: Organize your neighbors, do your homework, embarrass the bad guys, work the press, and win some modest victories, which then energizes neighbors to fight for bigger victories.

With her immense blond bouffant hairdo and street-smart bravado, Cincotta was great newspaper copy for her David-and-Goliath battles. When President Ford signed the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act, it was a banner headline story in the Chicago Tribune, crediting a jubilant Cincotta.

A second inspired leader was Monsignor Geno Baroni, a Pittsburgh-based radical priest. Local parishes in Pittsburgh and elsewhere were contending with racial blockbusting and dwindling congregations. Most of these neighborhoods were Catholic and ethnic—Irish, Italian, and Eastern European. Like Cincotta, Baroni taught that the enemy was not Black families seeking housing, but the cynical bankers and brokers exploiting fear and dividing neighbors by race.

Msgr. Baroni founded the National Center for Urban Ethnic Affairs to help local groups exchange information and strategies, working closely with Cincotta. A lot of these local groups were spearheaded by progressive parish priests. A not-so-secret source of their funding was Catholic Charities, the most progressive local face of the Church. It was a man-bites-dog story: white ethnics battling banks on behalf of racially integrated neighborhoods.

A third, Washington-based node of this growing national network was the Center for Community Change, which had originally been created as a citizen advocacy group to monitor Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. The CCC staffer in charge of community reinvestment issues, who testified at our first hearing, was Jeffrey Zinsmeyer. More than four decades later, he is a benefactor of The American Prospect.

So when an impressive array of local groups came to our first week of hearings, they already had the benefit of several years of strategic organizing and information exchange. Once HMDA and then CRA passed Congress, they were a citizen army primed for action.

In the 1970s, banks were more heavily regulated. The decision to open a branch required explicit regulatory approval. The legislation required the regulatory agencies to regularly review the banks’ community reinvestment records. This gave the groups even more leverage.

Even before CRA was enacted, when the first HMDA reports were released in 1976, community groups around the country, most of them affiliates of National People’s Action, began making good use of them. In Salt Lake City, a local group found that United Savings and Loan lent more than $11.5 million to non-redlined areas, but just $11,000 in the group’s target neighborhood. In Baltimore, a redlined community on the West Side got two mortgage loans totaling $100,000, while nearby middle-class Towson got $2.6 million.

At National People’s Action headquarters in Chicago, researchers tallied the national pattern. It all provided momentum to enact CRA. In March 1977, the Banking Committee held three more days of hearings, with Gale Cincotta and Ralph Nader as lead witnesses. This time, the new Carter administration was supportive. Robert Embry, the former housing commissioner of Baltimore who had worked with anti-redlining activists, was now assistant secretary of HUD. He called for a stronger bill.

Scouring the country, we found exactly two bankers to testify in favor: Ron Grzywinski, who had founded the South Shore Bank of Chicago explicitly to promote community reinvestment in homes and small businesses, and Todd Cooke, president of the much larger Philadelphia Savings Fund Society, an old-fashioned, nonprofit, Jimmy Stewart–style savings bank.

The hearing record was filled with extensive research reports by the community groups documenting extensive redlining. Proxmire’s remarks could have been written by Cincotta. “To criticize reinvestment incentives as credit allocation is disingenuous,” he said. “We already have credit allocation … and it is credit allocation for the Fortune 500.”

Once again, the banking lobby tried to kill the bill, and once again, the community groups mounted a massive grassroots lobbying campaign. Proxmire had to attach CRA to the 1977 Housing Act because it never would have survived as a stand-alone bill.

ONCE CRA BECAME LAW, the question became how aggressively regulators would police banks and enforce its reinvestment mandate. In 1978, an opportunity opened up with the confirmation hearing for a new chair of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, the agency that regulated savings and loans.

In early 1978, President Carter had made a major commitment for new public and private investment in cities. Carter’s term still had almost three years to run, and he had a strong Democratic majority in Congress. To fill the vacancy at the Bank Board, he nominated an old friend and Annapolis classmate, Robert McKinney, who had been president of an Indianapolis savings and loan. The hearings ran for three days and turned into a campaign for tough CRA enforcement.

Pressed by community groups as well as national consumer and civil rights organizations and key Senate and House members, McKinney reversed the Bank Board’s resistance to making maximum use of CRA. He “turned into a real tiger on the redlining issue,” Proxmire said. McKinney issued regulations banning all appraisal materials that referred to the racial composition of a neighborhood, and explicitly prohibited reference to the age or location of a home in its mortgage underwriting. “When I came in,” he later said, “the Bank Board was much too close to industry.”

Under McKinney’s new regulations, released in July 1978, each lending institution was required to produce a community reinvestment plan and indicate how it would meet its goals. In addition, the Bank Board created a $10 billion fund for below-market community lending. All of this added up to an even more explicit invitation for the community groups to hold both the lenders and regulators to their word.

As Rebecca Marchiel writes in her authoritative history of CRA’s first years, After Redlining, “[T]hese federal agencies empowered neighborhood groups as grassroots financial regulators … giving them the authority to interfere in banks’ business deals if the banks failed to meet social obligations to nearby communities.”

Now organizers could go into high gear. CRA, as interpreted by McKinney’s regulations and other agencies such as the FDIC, gave regulators the authority to block mergers or branch openings if the bank was failing to live up to its CRA commitments. Since this was new and unfamiliar territory for bank examiners, it fell to the community groups to compare the banks’ commitment on paper with their actual performance, and the community’s needs. This the groups commenced to do, with relish.

Working with National People’s Action, Ron Grzywinski, the pioneering Chicago community reinvestment banker, coached activists on lending practices, so that their demands would be well informed and realistic. In New York, activists used HMDA data and the CRA mandate to win the first CRA challenge. The FDIC confirmed the activists’ research showing that the Brooklyn-based Greater New York Savings Bank collected $594 million in deposits from the borough (this was pre-gentrified Brooklyn) but made only $7.5 million in mortgage loans. The FDIC then denied the bank’s request to expand into Manhattan.

As word spread of the power of this organizing tool, national groups such as ACORN and its local affiliates successfully made demands on banks not just to extend credit but to provide direct financial support to housing and community development groups and even to affiliates of activist organizations such as ACORN itself. In Boston, a lawyer named Bruce Marks, who systematically pressured bankers to make deals with community groups and provide them with financing, was regularly accused by bankers of extortion (to no avail).

Meanwhile, the Clinton administration embraced the ideal of community reinvestment as a New Democrat way of mobilizing private-sector funds to help poor people. Clinton met with the leaders of South Shore Bank and used it as a template for federal legislation to create a new kind of lender, the community development financial institution.

But this was also the era of toxic financial deregulation eagerly promoted by the Clinton administration and its top economic officials, Robert Rubin and Lawrence Summers. So while Clinton was supporting community reinvestment with one hand, he was sowing the seeds of the 2008 collapse with the other. The aftermath of the subprime disaster, which fell heavily on working-class and Black homeowners, would produce an epidemic of foreclosures that wiped out decades of good work on reinvestment.

Indeed, there was a kind of reverse redlining at work. Whereas before Black and Latino homeowners were excluded from credit, in the subprime era unscrupulous mortgage lenders sought them out, pitching them on risky cash-out refinances that saddled them with unaffordable debts when the housing bubble collapsed.

A bitter irony is that when CRA was being debated, bankers warned that it could lead to unsound lending. The bill’s drafters took pains to include language making clear that a bank had an obligation to serve community credit needs “consistent with the safe and sound operation of such institution.” Had regulators enforced that provision during the subprime era, when mortgage products were the antithesis of safe and sound banking practices, the 2008 financial collapse never would have occurred.

IN THE ERA OF SPECULATIVE BANKING that began in the 1990s, bankers were on a binge of mergers and acquisitions as well as the creation of lucrative and opaque financial products. Between 2000 and 2022, acquisitions cut the number of U.S. banks in half, from more than 8,000 to just over 4,000. Four mega-banks account for about half of all deposits.

In this climate, many bankers came to see community reinvestment as a Good Housekeeping seal. With banks reaping hundreds of billions from much bigger deals, tossing a few tens of millions at community reinvestment was useful cheap grace. Creating departments to promote lending in low- and moderate-income communities yielded good public relations and won praise from the regulators.

When I spoke at reinvestment conferences in the 1980s and 1990s, I was pleasantly surprised that many enthusiastic boosters of the idea were lenders. A whole cadre of loan officers and vice presidents who specialized in that kind of lending came of age in the CRA era. Some of their work was idealistic and sincere. Some of it was utterly cynical.

On the other side, a dense web of hundreds of local and state organizations address the interconnected issues of affordable housing, mortgage credit, racial justice, and urban poverty. For them, CRA is not a magic bullet, but a useful, if imperfect, tool.

At its best, CRA enables local groups and regulators to pressure bankers to be better citizens. “We’re constantly lamenting the limitations of CRA, but I can’t imagine where we’d be without it,” says Jaime Weisberg, who handles banking issues for the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development (ANHD) in New York City, a coalition of dozens of neighborhood groups and community developers. “Banks covered by CRA have to pay attention to us. Non-bank lenders completely ignore us.”

In 1990, local and state organizations that promote housing, community economic development, and banking services came together to form the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC), which now has more than 600 affiliates. NCRC provides national clout and expertise to monitor regulatory agencies, work with Congress and the administration, and negotiate commitments from banks.

Jesse Van Tol, a longtime NCRC staffer who became the organization’s second national president in 2018, succeeding John Taylor, had pioneered the idea of having NCRC negotiate community benefits agreements directly with banks, using the leverage of CRA. The actual agreements are with local community affiliates of NCRC. Since 2016, 20 such bank agreements have produced commitments totaling $548 billion for mortgages, small-business lending, support for community development corporations, and philanthropic donations to community groups.

The largest of these, finalized in May 2022, is a five-year, $100 billion commitment by U.S. Bancorp, the nation’s fifth-largest, which includes $47 billion in small-business lending to predominantly communities of color, and $31 billion for community economic development and affordable housing. In addition, there is a special fund of $100 million for down-payment assistance and below-market mortgage loans. This was agreed to in conjunction with a proposed merger between U.S. Bancorp and MUFG Bank.

The lead organization that orchestrated the pressure for this deal was the California Reinvestment Coalition, which generated 30,000 individual letters against the merger, and compelled regulators to hold a rare public hearing to listen to evidence on the bank’s poor performance.

Even if some of this new money might have flowed in any case, there is no doubt that CRA and the work of the activists has dramatically increased the flow of credit to low-income and communities of color. In some cases, banks seeking regulatory approval first come to NCRC and its affiliates to test the waters and see what they need to do to clean up their act.

This happened in 2014 when BB&T (now merged into a rebranded Truist Financial) sought to purchase Susquehanna Bank, an action that required regulatory approval. Before they announced the planned merger, BB&T executives met with NCRC leaders and local affiliates to formulate reinvestment plans. According to Marceline White, executive director of the Maryland Consumer Rights Coalition, this agreement became the rough template for NCRC’s national strategy of extracting community benefits agreements.

In very rare cases, a regulatory agency will initiate action to require a bank with a poor community reinvestment performance to devise a detailed action plan, even without the leverage of a pending merger or acquisition. In 2013, Birmingham, Alabama, bank BBVA was given a failing CRA grade by the Atlanta Federal Reserve. The bank worked with the Fed and community groups to develop a detailed reinvestment plan, and its grade went to outstanding.

ALL THIS GOOD WORK, HOWEVER, is at risk of being overwhelmed by larger trends, just as the financial collapse of 2008 wiped out three earlier decades of reinvestment efforts. Paradoxically, approval of mergers can be conditioned on CRA ratings. So a good CRA record blessed by the local reinvestment groups can provide a safe-conduct pass for bankers seeking merger approval. Yet merged banks have now become so large that CRA enforcement becomes ever more difficult in practice.

In the absence of better antitrust scrutiny and tougher enforcement of the Bank Merger Act, the problem is much bigger than CRA. “I don’t know that many of these mergers would be denied, even without community benefits agreements,” says Kevin Stein of the California Reinvestment Coalition. Indeed, the Federal Reserve has not blocked a single bank merger application since at least 2006.

Banking in the United States traditionally was local. The federal prohibition on interstate banking was repealed only in 1994. The original CRA, written in an era when banking was far more local, referred to a bank’s obligation to serve “the needs of the communities in which they are chartered.”

But how do you apply that to, say, Bank of America, a $2 trillion behemoth with 4,300 branches and 66 million customers? Under current CRA regulations, a bank gets to define its “primary service area.” Bank of America defines its primary service area as the greater Charlotte metro area (where the bank is headquartered), plus the entire states of California and Massachusetts.

In reality, however, B of A is active nationwide. For instance, it accounts for 48 percent of deposits in the city of Baltimore, ground zero for disinvestment, but only 2 percent of Baltimore mortgages, according to research done by the Maryland Consumer Rights Coalition. The coalition has tried to make an issue of this with both the bank and its regulators, but to no avail. “The regulators won’t touch this,” says White.

Another issue that CRA fails to reach in practice is the problem of branch closures. Poor people and people of color are disproportionately unbanked, leaving them at the mercy of far more expensive sources of credit such as payday lenders (which have storefront offices conveniently located throughout low-income urban neighborhoods). Oddly, banks must pass muster with CRA before they can open a branch but get no demerits for closing branches, which are considered legitimate business decisions.

Banks have closed more than 7,500 branches between 2017 and 2021, according to NCRC, and more than one-third of these closures were in low- and moderate-income or majority-minority neighborhoods. While middle-class people increasingly bank online and seldom set foot in a branch, if normal banking services are to be extended to America’s poor, this will require more branches, not fewer ones.

But banks view branches as cost centers and make little if any money on small, low-income customers. Since CRA covers all banking services to low- and moderate-income communities, you might think that branch closures would be a major concern. Though community groups have tried to make an issue of this, regulators won’t.

According to NCRC, about 98 percent of banks get CRA ratings of satisfactory or outstanding. About 2 percent are rated as “needs improvement,” and hardly any get failing grades. Light-touch regulation has created a Garrison Keillor kind of world where every bank is above average.

There are other new challenges that CRA simply doesn’t reach, such as gentrification. In the 1960s and 1970s, the white middle class was fleeing cities. Today, with housing so unaffordable, many majority-minority urban neighborhoods are both trendy and offer relative bargains. The phrase “changing neighborhoods” has the opposite racial meaning from the one it had half a century ago.

In the absence of serious national policies to increase the supply of affordable housing, a bank that makes loans to a marginal neighborhood may get regulator credit for accelerating the process of gentrification. CRA researchers who look at race told me that a white working-class family has an easier time getting a mortgage loan than a Black middle-class family.

Yet the very existence of CRA and the activism it facilitates can influence bank behavior, even when a given activity is not expressly covered by the regulations. In New York, landlord harassment of tenants covered by rent stabilization laws and illegal forced evictions are a huge issue. The Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development and its member organizations use a variety of tactics, from direct actions against landlords to lawsuits, to work with city officials and the state attorney general.

CRA doesn’t technically cover bank financing of redevelopment by scofflaw landlords. Banks get CRA credit for good lending but don’t get downgraded for bad lending. Advocates say that they should. But in the meantime, it is still useful leverage.

According to Jaime Weisberg, Signature Bank in New York has a long record of lending to abusive developers. ANHD has developed a code of best practices for banks, which includes not financing toxic landlords. “We had a two-year campaign against Signature to accept best practices,” Weisberg says. “They refused. Then they applied to open a branch, we contested it, and then they accepted best practices.”

AT ITS BEST, CRA PROVIDES SYNERGY between regulatory strategy and movement tactics. The reinvestment campaign has maintained this alliance, though today the experts using the leverage of CRA regulations are more likely to be lawyers and professional researchers than neighborhood activists, as they were in Gale Cincotta’s day. But Cincotta, who died in 2001, would be pleased with the alliance of organizers and experts that she spawned.

One encouraging prospect is that basic CRA regulations are being revised and strengthened for the first time in 27 years, with a more progressive assortment of bank regulators than in many decades. At the FDIC, Martin Gruenberg, a Senate Banking Committee alum, is back in his old role as chair. The new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, an Elizabeth Warren invention, is headed by progressive Rohit Chopra. At the Fed, the general vice chair is Lael Brainard, a moderate liberal who has long made community reinvestment her calling card with progressives. The only disappointment is the acting head of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Michael Hsu, a centrist Treasury official who got the job after the proposed appointment of a progressive, Saule Omarova, was blocked by corporate Democrats in the Senate. But even Hsu is a CRA booster.

The notice of proposed rulemaking, released on May 5 by the three lead agencies (the FDIC, the Fed, and the OCC), outlines a general toughening. It proposes much more detailed tests of whether banks are meeting their community reinvestment obligations, including separate categories of evaluation such as retail lending, and community development. They also propose holding banks accountable for all of their lending, not just in a self-selected service area.

The new rules are also expected to deal with what advocates criticize as “grade inflation,” toughening the criteria for banks to get a satisfactory or an outstanding CRA grade. The agencies are guardedly receptive to more of a focus on race. CRA doesn’t explicitly mention race, though it is clear from the statute that the redlined communities the law requires banks to affirmatively serve were and are heavily majority-minority.

The reinvestment groups are encouraged by the direction of the regulators’ proposals, though they find them inadequate in several respects. NCRC has called for explicit evaluation of a bank’s lending record on race, as well as much tougher standards for merger approvals, the requirement of public hearings, and a good deal more. “Regulators have not ever denied a major bank merger; they’ve never met a bank merger they didn’t like,” says Van Tol. “Community groups have used leverage to get benefits agreements, but regulators ought to condition mergers on very clear and significant benefits to the public, or else deny them.”

The comment letter from the California Reinvestment Coalition proposes 12 areas for tougher enforcing, including this one: “Lower ratings if there is evidence of harm (such as discrimination, displacement, fee gouging, high-cost lending, lending that results in undue defaults, branch closures, and fossil fuel finance or other forms of climate degradation) as evidenced by court cases, regulatory actions, investigations, consumer or fair housing group complaints or community contacts/comments.” Rep. Maxine Waters (D-CA), chair of the House Financial Services Committee, has introduced legislation making tougher criteria statutory.

Another excellent and emblematic comment letter, from the Metropolitan Milwaukee Fair Housing Council, calls for more explicit evaluation of banks’ lending records based on race, downgrading of banks for displacement and predatory lending practices, a presumption of disapproval of mergers unless they can show clear benefit to communities, penalizing banks for closing branches, and a good deal more.

The sophistication with which the advocates approach this effort is impressive. At the level of technical analysis, they are a match for the legions of high-priced lawyers and lobbyists in the pay of the banks.

In the end, one has to conclude that both the advocates and the regulators have been taking the community reinvestment frame about as far as it can reasonably be expected to go. The David-and-Goliath struggle launched by Gale Cincotta more than 50 years ago is still bearing fruit. But remedy of the deeper structural abuses of the banking system, the continuing blight of racism, and the failure to provide affordable housing will require much more radical reform of American capitalism.