In “Building Resilient Organizations: Toward Joy and Durable Power in a Time of Crisis,” Maurice Mitchell unpacks the interrelated tasks facing our movements today. He identifies internal issues that have roiled and sometimes broken organizations over the last few years while pointing to the “challenging terrain on which we struggle and grow.” The piece can contribute a lot to evaluating the ways we work—but it is not primarily a management guide. It is a call to clarify our ideology and strategy and use those to anchor all our decisions and practices. Nothing else will do if we are to move forward in this time of overlapping crises and distinct opportunities. Mitchell offers his article as a starting point. To feed and stimulate our collective reflection, Convergence and The Forge are presenting a series of responses. Here, Kim Fellner draws on her experience with the National Organizers Alliance to look at the persistence—and shifts—of the challenges movement organizations face.

Ever since the Boomers swarmed onto the scene, scholars have been driven to explore the intertwined concepts of age (stage of life), generation (shared with others of a similar age) and period (the formative, shared events and circumstances of the times in which we live). Maurice Mitchell’s piece, “Building Resilient Organizations: Toward Joy and Durable Power in a Time of Crisis,” provokes us to consider the intergenerational conflicts and power struggles that are endemic to movement life and how those are shaped by the current moment.

Mitchell suggests that too many left-leaning organizations are currently riven by either/or battles, pitting identities and generations against each other along our ideological, structural and cultural fault lines, while the solutions generally dwell in the realm of both/and. His call to maximize our collective power is particularly important at this perilous moment when multiple plagues are forcing us to rise to new levels of ingenuity, capacity and courage.

He is not alone. In the midst of pandemic times, I got a call from Alex Tom, who’s been a movement leader for more than 20 years. He was asking about the National Organizers Alliance (NOA), an organization which I helped form in 1991, and where I served as executive director for roughly a decade. Designed “to advance progressive organizing for social, economic and environmental justice and to support, challenge and nurture the people of all ages who do that work,” NOA existed from 1991-2003, before it faded into history. “I heard NOA developed a handbook on how to treat each other in our organizations and movement,” he said. “So where is it?”

I had almost forgotten about Practicing What We Preach: The NOA Guide to the Policies and Practices of Justice Organizations; miraculously, there it was, on top of the first box I opened, and I sent it off.

I also reread it, and was startled by how timely it felt. Back in 2001, we observed that “the culture of movement work favored those with other economic or social support systems, people with limited responsibilities, and those willing to place their work above their health or their families. Mirroring our larger society, these factors of privilege and priority generally meant that the field was dominated by white males, even as the ‘troops’ became more diverse.”

NOA was a place where organizations often came for recommendations about personnel policies and organizers came for advice when they were teetering on the edge. “Practicing What We Preach” was an effort to compile those individual consults into a more systematic approach to “identify both the written policies and the organizational texture between the lines that either encourage or deter longevity and joy on the job.”

“In focus groups and interviews, ED’s and line organizers alike told us how desperately they want vibrant healthy organizations. They described the need for much greater support from funders, boards and other organizers to achieve better treatment, pay and training. They were eloquent about feeling trapped by insufficient resources, combined with a lack of good models and an absence of supervisory training and staff development.”

Sound familiar? Mitchell’s piece shows that the search for joy on the job is still a work in progress.

Time Travel

Revisiting those NOA documents exposed how the quest to integrate race, class and gender into a compelling framework—both in the work we do, and in how we do it—remains a challenge across multiple generations, from Boomer to Gen Z. Back in the NOA days, those of us animated by the civil rights and anti-war movements, leavened by a redefinition of women’s and gender rights, were coming into our own, carving out new territory in an organizing landscape defined by New Deal labor and the community organizing practices of Saul Alinsky. And pretty much white-male-dominated.

-

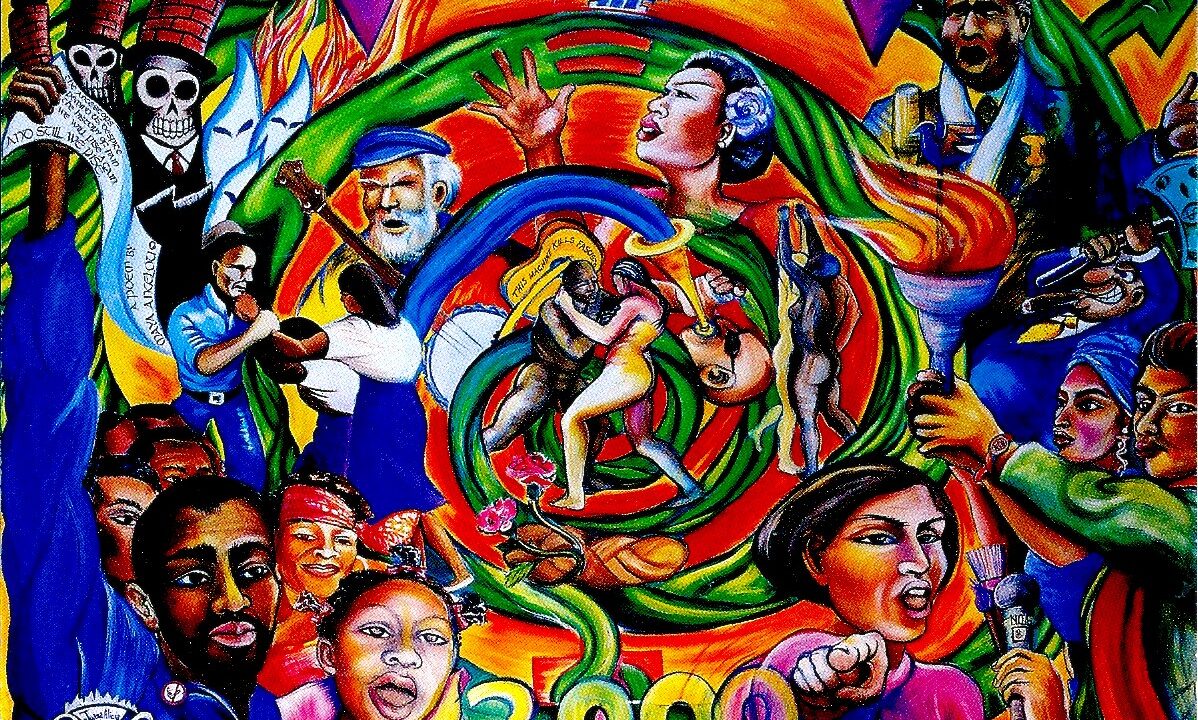

NOA was initiated and structured to model diversity across identities, generations, regions and organizing endeavors in a way that was unusual for its day. It served as a bridge among labor, community and issues organizers who otherwise might not have met. Our gatherings, vibrating with arts and humor, introduced a different kind of relationship space that seeped into the broader movement.

-

We made a real stab at combining the nitty-gritty craft of organizing with a nurturing culture. We established a multiple-employer pension plan for movement groups, which included an employer contribution, and fought hard to get organizations to participate. We learned from seasoned practitioners, but provided lots of space for younger and less-heralded people to shine.

-

We were brave and creative in the conversations we shared, even when they were difficult and contentious. Of particular note was a rowdy debate about Alinsky organizing vs. organizing which explicitly incorporated race and gender issues, embodied in a set of training modules called Social Justice Dialogues. One unit featured seven “sacred cows of organizing” mooing their way across the stage. “I’m the sacred cow of harmony,” one proclaimed. “We need to focus on what we have in common. Identity politics just amplify our differences. Why work on anything that’s internally divisive when there’s so much that unites us? Remember: if we all work together, and we all just get along, barriers of race, class, and gender, will come tumbling down! Moooo.” The discussion was long overdue but, in retrospect, it also held the seeds of the identity extremes that Mitchell identifies. And it generated a level of hostility from which the organization never fully recovered.

Generational Swing Shift

In the end, despite the effort to “practice what we preach,” NOA failed to survive. But the movement dilemmas with which we grappled live on, redefined by the current political and cultural moment that informs Mitchell’s analysis.

We are witnessing a transformative demographic shift toward a more diverse population, increasingly reflected in a more diverse cohort of movement leadership. But we are also seeing the direct convergence of several activist generations in the same organizational space–and that is quite different from the Boomer experience.

When I entered the field in the early 1970s, many of the 1950s generation of leftist thinkers and organizers had been purged as a consequence of anti-Communist witch-hunts. That vacuum of progressive leadership meant that we often had to seek our role models and mentors from a few generations back and outside our institutions. In addition, many of my peers started their own organizations, vastly expanding the progressive nonprofit sector, enlarging the range of issues and campaigns and diversifying the ranks of nonprofit staff. With few avowed leftists from older generations sharing our office space, we had only each other to fight for greater vanguard status, which, of course, we did–with gusto and some very debilitating consequences.

In contrast, we currently have several generations, from Gen Z through the Boomers cohabiting in our organizations. Each generation is deeply invested in its practice of Left culture and ideology, and convinced of its righteousness. This can lead to some contention; consider, for example, the current dust-ups between the “toughen up” stance of veteran organizers and the self-care focus of next-gens.

A biproduct of this ferment is the emergence of a “sandwich generation” in our organizations: Movement leaders in their 40s and 50s are caught between the hectoring (and predominantly white) departing Boomers on the one hand, and the demanding Millennials and Gen Z’ers on the other. That sandwiched generation notably includes senior staff of color. Just as they are finally reaching their peak in terms of expertise and power, some are deciding to leave the field–a loss likely to yield greater organizational churn and less of the institutional heft that durable power requires.

Unionizing for Good

Some of these struggles are currently figuring into a wave of unionization drives within our progressive organizations.

Roughly a month before Mitchell’s piece landed, fellow unionist Larry Kleinman and I circulated “Adjusting and Trusting,” a guide for progressive managements and staffers grappling with how to undertake unionization without destroying the organization or each other. We were motivated by stories from hair-on-fire colleagues about unionizing processes that embodied many of the trends that Mitchell explicates: generational conflicts; desperation and exhaustion about the political moment; conflicts over leadership structures; and the demand for ideological purity over functional progress.

As lifelong unionists, Larry and I believe that all workers should have union representation–including those in the progressive movement sector. Mitchell too elevates unionization as a positive force to “increase clarity, promote equity, foster accountability and provide a common language across an organization.”

However, as Mitchell tactfully implies, and as emerged in our research, the process of unionization can also become a way for some staff to burnish their left-vanguard credentials by calling out managerial leadership for being insufficiently left and/or inadequately anti-racist. Ironically, these attacks often place newer directors of color in the crosshairs, threatening some of the hard-won victories to diversify top leadership in justice organizations.

In addition, some unionizing staff demand that their contract be the vehicle for resolving all the ills of capitalism or racism, making it difficult to reach an agreement that rationalizes institutional structures and improves working lives. One approach to ease these skirmishes might be to work with labor to create a sectoral approach to unionization, with core principles and templates for contracts based on staff/budget size and regional/national focus, with room to customize for unique organizational circumstances.

Choosing Our Fights–And Our Sides

Maurice Mitchell concludes his article with some recommendations for how to promote structural, ideological, strategic and emotional wellbeing in our organizations, to help us toward greater joy, power and movement success. Here are a few we might add. Although they don’t fit neatly into the schematic, they’ve helped keep me going:

-

Identify and value bridge-builders who can navigate complex and nuanced relationships and perspectives. As one of my mentors, Gary Delgado, noted, people who span a range of constituencies can often provide the key to substantive change.

-

Learn to count noses. Whether it’s knowing how to get people to a meeting, craft a strategy or win an election, you need to be able to rigorously assess who’s with you, who’s wavering, who isn’t. It can keep us grounded, realistic and accountable.

-

Err on the side of generosity. Assume reciprocal good will for as long as you possibly can. Admit what you don’t know, share what you do.

-

Don’t look inward so much that you forget to look outward toward your current and potential constituency. Don’t let the internal conflicts become more important than the work itself.

-

Consider what truly matters, not just for you but for the collective, not just for the moment but for the movement. We are part of a historical continuum; those who come after us will need our shoulders on which to stand.

No matter what age or generation we are, we are sharing these tumultuous times, challenged by climate devastation, a digital upheaval, advancing authoritarianism–plus white supremacy, religious patriarchy and economic inequality that just won’t quit.

However, adherence to a rigid, rhetorical ideological frame too often circumscribes and limits our imagination and empathy to build the majoritarian consensus needed to expand our gains. This was brought home to me during the 2020 primary season when I went to meet a friend at a progressive-side think tank in Washington, DC. I was in the lobby chatting with the genial African American security guard, when a long-time white staffer of said think tank got off the elevator and, in the course of a brief exchange, half-jokingly chided the security guard for supporting Biden.

Guard: “That’s right, I am. I want to win.”

Staffer (to me): “He (the guard) also supports the Hyde Amendment.”

Guard: “Yes, I do.”

Staffer scoffs and rolls her eyes

Me: (to staffer) “Wait, this man is on our side.”

Guard: “That’s right I am.”

Staffer: “Sure, I guess we’re all human.”

Me: “No, I mean he’s on our side. Part of our team…”

Guard: (laughing) “Yes I am.” Then, turning to the staffer, “You’re just like Trump.”

As progressive organizers, a lot of what we do requires that we be in conversation with people about how to balance out the rights of individuals with the conditions needed for the common good—and do it with enough people that we can win both personal transformations and systemic change. That requires extending beyond ourselves to embrace a more generous definition of who is on our side.

As Mitchell’s piece suggests, while we need to challenge each other to practice the values we preach, we have little to gain by drawing that line against each other. Or, as one of my NOA colleagues, the late Dave Beckwith put it, our hope is, “a movement of organizations where the staff is learning and growing throughout a long career, where we can be whole and healthy persons, where we can follow the pull of our passion for justice, and mentor a next generation that’s better than we are.” And let us say amen.