We’re happy to be able to excerpt Chapter Two of The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make Them Pay by Gabriel Zucman and Emmanuel Saez as part of our discussion of inequality, taxes and economic, social and racial justice.

The chapter is a great introduction to tax policies and the fight for tax justice throughout American history, and to the deeply immoral legacies, sharply progressive innovations, energetic popular movements and tireless struggles for fairness that make up this history.

A few key take-aways:

-

Wealth taxes are an American invention — as are sharply progressive top income tax rates.

-

Nobody except the ultra-rich was ever subjected to America’s confiscatory top tax rates.

-

American anti-tax rhetoric is grounded in white supremacy and the ideology of wealthy oligarchs and slaveholders in the South.

-

After the Civil War, Wall Street oligarchs adapted and promoted the anti-tax rhetoric of the South nationwide.

-

Extreme inequality drives popular outrage — and progressive tax policies.

-

High taxes on the rich diminish greed and inequality — sky-high wealth and income are earned at the expense of the rest of society, and taxing them heavily to invest in public goods makes the economy more broadly prosperous and more fair.

-

Ownership of corporations is the key source of economic and social power — so high corporate taxes are an important part of assuring fairness in the economy.

-

Allowing tax avoidance is a choice governments make: it’s possible to eliminate tax dodging if lawmakers and regulators make it a priority.

Thanks again to the authors and to their publisher, W.W. Norton & Company.

The history of taxation in the United States is anything but linear. It’s a story of dramatic reversals, of sudden ideological and political changes, of groundbreaking innovations and radical U-turns.

From 1930 to 1980, the top marginal income tax rate in the United States averaged 78%. This top rate reached as much as 91% from 1951 to 19631. Large bequests were taxed at quasi-confiscatory rates during the middle of the twentieth century, with rates nearing 80% from 1941 to 1976 for the wealthiest Americans.

Some commentators look at this history and dismiss the idea that high marginal rates were ever successful as policy. In practice, they maintain, hardly anybody paid the full rate and loopholes were plentiful. America, according to this view, may have appeared to tax the rich, but never genuinely did so.

So, did America’s ultra-wealthy ever contribute to the public coffers a large fraction of their income? And if they did, was this only in the context of world wars, or did progressive taxation extend beyond the wars and reflect broader choices about justice and inequality that may still have a bearing on today’s tax debates? To address these questions, we must consider the comprehensive, long-run evidence on the evolution of the effective tax rates imposed on the various groups of the population. By extending the computations presented in the previous chapter over more than a century, we’ll see how progressive exactly the US tax system used to be. We’ll see also how America pioneered some of the key progressive fiscal innovations in world history, often paving the way for other countries.

Of course, there is no such thing as an “American way” of taxing—not any more than there is “a French way” or a “Japanese way.” There are specific national trajectories, experiments, institutional tinkering, breakthroughs, and retreats. Like that of other countries, America’s fiscal history is deeply linked with the dynamic of inequality, the transformation of beliefs about private property, and the progress of democracy. Understanding this history offers a window onto understanding the conditions for change today.

The Invention of Wealth Taxation in the Seventeenth Century

Ever since they arrived in the New World, the settlers of the Northern colonies—from New Hampshire to Pennsylvania—cared about making sure the affluent contributed to paying the common bills. In the seventeenth century, they developed incredibly modern tax systems for their time. The key innovation? Taxing wealth. Not only real estate and land, as England already did at the time. But all other assets too, from financial assets (stocks, bonds, loan instruments) to livestock, inventories, ships, and jewelry.

As far back as 1640, the colony of Massachusetts taxed all forms of property2. Although valuation methods differed over time and across states, the general principle held that prevailing market prices were to be used to assess the taxable value of each asset. When market values were not readily available, they were estimated by elected local assessors or computed by applying multiples to the income flow generated by the assets. A house that could be rented for £15 annually, for example, was deemed to be worth £90 (six years of income) and taxed as such in Massachusetts in 1700.

The colonies’ tax systems, to be sure, were not perfect or even fair by today’s standards. Their wealth taxes had serious limitations. Their rates were low and they were not progressive. Wealth taxes were supplemented by levies that disproportionately hit the poor, such as import duties and poll taxes—flat, per-person levies. Some colonies, such as New York, relied more on regressive consumption taxes than on property taxes to fund public expenditures.

But overall the tax systems of Northern colonies were unusually progressive for the time. They were far more advanced and democratic than anything that existed in Europe. Take France, the most populous country of the Old World. While Massachusetts made a serious attempt at taxing the rich, French kings pampered the affluent and bludgeoned the populace. France had an income tax (taille), whose main claim to fame was that it exempted almost all privileged groups: the aristocracy, the clergy, judges, professors, doctors, the residents of big cities, including Paris, and, of course, the tax collectors themselves—known as the fermiers généraux (tax farmers). The most destitute members of society, at the same time, were heavily hit by salt duties—the dreaded gabelle—and sprawling levies (entrées and octrois) on the commodities entering the cities, including food, beverages, and building materials. Since everybody needed food and salt (this was before refrigeration) the levies on consumption that formed the backbone of tax collection in the Old World were much less progressive than New England’s property taxes3.

The Two Faces of the New World

Taxation in the Northern colonies was also far more progressive than anything that existed in the South. Up to the outbreak of the Civil War, the tax system of Virginia—the largest Southern colony—consisted essentially of a poll tax and myriad levies on necessities. While Massachusetts had developed an elaborate system to assign values to every form of wealth, Virginia made no effort to put any value on anything. The main source of revenue? Levies on pounds of tobacco, cows, and horses, the number of wheels in carriages, billiard tables—and poll taxes4. During the eighteenth century, the taxes in Thomas Jefferson’s home state were even more archaic than in Louis XVI’s France. Income taxation was nonexistent; property taxation restricted to land.

As in the North, there were variations in tax policy among various states, but in general taxes in the South were more regressive. In her masterly book American Taxation, American Slavery, historian Robin Einhorn shows the deep link between this backwardness and slavery. A fear haunted the slaveholders of the South: that non-slaveholding majorities would use taxation to undermine—and eventually abolish—the “peculiar institution.” They particularly feared wealth taxation: at a time when 40% of the population in Southern states was considered property, property taxes were an existential threat for slaveholding planters. They fought such taxes tirelessly, and for two centuries wielded their power to keep taxes and public institutions archaic. How? By stifling democracy.

In lieu of elected local governments, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Virginia operated with a system of self-perpetuating local oligarchies. Offices carried life tenures and were transmitted from one generation of plantation owner to the next; county court members were appointed on recommendation of the incumbents. When Virginia’s planters did not appoint themselves as tax collectors, they bribed whoever had the job. When property taxation eventually emerged, landowners self-assessed the value of their land. Unsurprisingly, they used ridiculously low values. Virginia’s voters would wait until 1851 to elect their governor for the first time.

“Americans hate taxes! It’s in their DNA!” You’ve heard this anti-tax rhetoric many times. It has a few recurring clichés: That one of the key founding political acts of the United States, the Boston Tea Party of 1773, was a tax revolt. That Americans, contrary to Europeans, believe in personal responsibility, in upward mobility, in the notion that everyone, through hard work and ingenuity, can make it to the top. That the poor, in the United States, see themselves as temporarily embarrassed millionaires5. America, so this logic goes, hates taxes and is only true to itself when it is “starving the beast.”

To find the wellspring of this rhetoric, Einhorn teaches us, do not look to Boston, Massachusetts. Look to Richmond, Virginia. Look not at the common men longing for liberty; look at the slaveholders who fought to defend their immense but precarious wealth. Perhaps more than any other social group, they are the artisans of the anti-government belief system that, in various forms, suffuses American history. They embraced the supreme primacy of private property—even when that property consisted of human beings. They railed against the evil of “inquisitorial” income and wealth taxes that allow tax collectors to “invade” private homes. They invoked a looming “tyranny of the majority” that sought to impose “spoliation” upon a small group of wealthy citizens. While the sources of anti-government sentiment in America are complex, over the last centuries, few have done more to perfect the anti-tax narrative than Southern slaveholders.

After the outbreak of the Civil War, this long-standing antipathy toward taxes and democratic governments severely handicapped the Confederate states. Because they mostly relied on tariffs, revenues collapsed when the Union blocked Southern ports. With little experience collecting taxes on income and wealth, the Confederacy was unable to recoup the lost revenue; it had to rely on debt to fund the war against the Union. As the Confederate government issued more and more bonds, inflation skyrocketed.

The Union, by contrast, built upon an existing tradition of direct taxation to fund the war effort. The Revenue Act of 1862 created the Internal Revenue Bureau. In the same year, the first federal income tax was levied with a rate of 3% on income above $600 and 5% above $5,0006. The $600 exemption threshold was equal to about four times the average income in the country, or the equivalent of $250,000 today7. So the tax, albeit with small rates, was progressive. The Revenue Act of 1864 increased the rates to 5% on income over $600, 7.5% over $5,000, and 10% on income over $10,000—the equivalent of more than $3 million today. The law mandated a public disclosure of income tax payments, and in 1865 the front page of the New York Times listed the income of New York’s moneyed elite: William B. Astor declared an income of $1.3 million (5,200 times the average income of the time, the equivalent of $400 million today); Cornelius Vanderbilt, $576,551 (the equivalent of $170 million today), and so on8. The Union also borrowed heavily to fund the war and inflation increased a result, but much less than in the South9.

When the Income Tax Was Unconstitutional

After the abolition of slavery in 1865, wealthy industrialists piggybacked on the slaveholders’ rhetoric to fight the income tax created during the Civil war. They recycled and updated the Southern oligarchs’ well-oiled argument against the evils of interference with private property. In 1871, the Anti-Income Tax Association was created in New York. It brought together some of the great fortunes of the time: William B. Astor, Samuel Sloan, and John Pierpont Morgan Sr., among others10. And the association’s efforts were successful: the income tax, whose rates had already been reduced by Congress after the war, was repealed in 1872. It would remain in limbo until 1913 despite many efforts by reformers to reinstate it during the Reconstruction era and the Gilded Age that followed.

The efforts to reintroduce progressive taxation during the late nineteenth century had two main justifications. The first was blatant unfairness in the federal tax system. From 1817 until the cataclysm of the Civil War, Congress had levied only one tax: the federal tariff on imported goods. On top of the progressive income tax introduced in 1861, the Civil War had seen the proliferation of excise taxes on just about everything: luxury goods, alcohol, billiard tables, playing cards, but also corporations, newspaper advertisements, legal documents, manufacturing goods, and so on. Some of the newly created internal taxes—as these levies on domestic consumption were called, in opposition to the tariff, an “external tax”—were repealed after the defeat of the Confederacy, but others remained. In 1880, internal revenues accounted for a third of federal government tax receipts; the import tariff for the remaining two-thirds11. In both cases, the burden of federal taxes heavily fell on the shoulders of the poor. After they succeeded in abolishing the federal income tax, the great fortunes of the Gilded Age barely paid any federal tax; virtually all federal government revenue originated from consumers.

The second—and novel—development that catalyzed reform efforts was the upsurge of inequality. As rapid industrialization, urbanization, and cartelization took hold, it was impossible not to notice that fortunes were getting more and more concentrated. Economists made efforts to quantify inequality. In 1893, George K. Holmes, a statistician from the Department of Agriculture, used data from the 1890 Census and contemporaneous lists of millionaire families to estimate that the top 10% of households owned more than 71% of the nation’s wealth12. Others obtained similar findings13. It was a large increase over antebellum levels of inequality, when the top 10% owned less than 60% of total wealth. Of course, the estimates of wealth concentration for the nineteenth century have their margin of error14. Absent any federal income or wealth tax, the primary material to estimate inequality was limited. Alongside rising inequality came a growing demand, in the upper echelons of society, for denying its rise. Economists were distorting the facts; their statistics were faulty. But to anybody who was paying attention, there was no doubt that a dramatic development was under way.

The case for progressive taxation grew. A number of economists—most prominently Edwin Seligman, a professor at Columbia University—explained why an income tax was a necessary step to “round out the existing tax system in the direction of greater justice.”15 Bills were introduced in Congress—usually following an economic crisis, such as the Panic of 1873 and that of 1893—to reinstate a progressive income tax. These legislative efforts were supported by an emerging progressive and Democratic coalition representing Southern whites and poor and middle-class white voters from the Northeast and the West. They were opposed by the new alliance between Southern elites and Northern industrialists. For the well-to-do, income taxation was “inquisitorial,” “class legislation” to please “Western demagogues.” It infringed on privacy. Perhaps worse, according to New York senator David Hill, it was “un-American,” imported by “European professors.”16

An income tax bill nonetheless passed Congress in 1894, with a rate of 2% for income in excess of $4,000—about twelve times the average per adult income of the time, or the equivalent of $900,000 today. The debate that followed revolved around the issue of whether a federal income tax was constitutional. According to the Constitution, direct taxes had to be apportioned among the states according to the population of each state. For example, if 10% of the US population lived in the state of New York, 10% of tax revenue had to come from there—even if a third of national income was earned in that state (which was roughly the case at the end of the nineteenth century), and even if most taxable individuals (those earning more than $4,000) lived there. Neither the 1894 income tax nor the one of 1862 were apportioned among the states, because apportioning them would have been nonsensical: it would have forced the government to tax the rich very little in the states where they were over-represented (such as New York), defeating the whole purpose of progressive income taxation.

Though it mandated that direct taxes be apportioned, the Constitution did not define the term “direct tax.” In a famous moment during the Philadelphia Convention, on August 20, 1787, Rufus King, a delegate for Massachusetts, asked, “What was the precise meaning of direct taxation?” No one answered. Was a federal income tax a direct tax? Or did the term only refer to poll taxes and levies on land? The Supreme Court took up the issue in 1895. Ruling in Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan and Trust Company, the justices declared that the federal income tax was a “direct tax,” and as such had to be apportioned among states according to their population. This decision meant that the 1894 income tax was unconstitutional, which led to its repeal. For the rest of the Gilded Age, all federal government revenue would originate from tariffs and excises on tobacco and alcohol.

And Progressive Taxation Was Born . . .

After the Pollock decision, creating a progressive income tax was only possible if the Constitution changed. This hurdle was cleared in 1913, when three-quarters of the states ratified the Sixteenth Amendment following its adoption by two-thirds of both houses of Congress in 1909—the two steps required to amend the Constitution. “The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States,” reads the amendment. A federal income tax was enacted that same year.

The United States did not pioneer progressive income taxation. The policy’s rise in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century was an international phenomenon. Germany, Sweden, and Japan were the first countries, between the 1870s and 1890s, to create progressive income taxes other than for emergency war funding purposes. The United Kingdom quickly followed suit. Where the United States innovated was in quickly making its income tax highly progressive. In 1913 the top marginal tax rate in the United States was 7%. As early as 1917 it reached 67%. At that point, no other country on the planet taxed the affluent so heavily.

The reasons for the sharp increase of tax progressivity are multifold17. There was a desire to prevent war profiteering during the First World War—the type of profiteering that had enriched so many during the Civil War. To prevent a “shoddy aristocracy” from emerging again, an excess profits tax was imposed during the conflict. At first it covered the munitions industry only; then after America entered the war in April 1917, the tax was extended to all firms. All profits made by corporations above and beyond an 8% rate of return on their tangible capital—buildings, plants, machines, etc.—were deemed abnormal. Abnormal profits were taxed at progressive rates of up to 80% in 1918.

Even though it played a role, it does not seem that the war context was the key impetus for the rise of tax progressivity in America. None of the countries involved in the war were keen on encouraging war profiteering; each belligerent imposed an excess profits tax on domestic business. But no country increased its top marginal income tax rate as drastically as the United States (though the United Kingdom came close). More than the mere product of exceptional wartime circumstances, the rise of progressive taxation in America stemmed from the intellectual and political changes that had begun in the 1880s and 1890s: the evolution of the Democratic party, brutally segregationist in the South, but eager to unite low-income whites in the North and the West against Republican financial elites by means of an egalitarian economic platform; the social mobilization in favor of more economic justice, in a context of surging inequality and industrial concentration. Simply put, a growing fraction of the population refused to see America become as unequal as Europe, which at the time was perceived as an oligarchic antimodel18. The economist Irving Fisher captured this mindset when he denounced the “undemocratic concentration of wealth” in his address to the American Economic Association in 191919.

And so it was that, in peacetime, the United States pioneered two of the key fiscal innovations of the twentieth century.

The first of these innovations was the introduction of a sharply progressive tax on property. As we have seen, by the beginning of the century, US states already had a long history of property taxation behind them. But these property taxes had a major limitation: they were not progressive. The same rate applied to all property owners, regardless of their wealth. There had been efforts to make these taxes progressive over the course of the nineteenth century, but they had failed as states adopted “uniformity clauses” mandating that all assets—no matter their nature (real or financial, for instance) or the wealth of their owners—be taxed at the same rate20. In 1916, the federal government introduced its own progressive tax on property, in the form of a progressive tax on wealth upon death: the federal estate tax. Its rates were initially moderate: in 1916 the top estate tax rate reached 10% for the largest estates; it rose a bit during World War I before stabilizing at 20% in the late 1920s.

This changed between 1931 and 1935, when the rate applying to the top fortunes rose from 20% to 70%. It would hover in the 70%–80% range from 1935 to 1981. Over the course of the twentieth century, no continental European country ever taxed large successions in direct line (from parents to children) at more than 50%. The only exception? Allied-occupied Germany between 1946 and 1948, when tax policy was decided . . . by the Americans, who imposed a 60% rate21.

The second tax policy innovation was even more far-reaching. From its creation through to the 1930s, the goal of the income tax had been to collect tax revenue. The tax compelled the rich to contribute to the public coffers in proportion to their ability to pay. After his election, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt added a new objective: Make sure nobody earns more than a certain amount of money. In short, confiscate excessive incomes. In 1936, he increased the top marginal income tax rate to 79%; in 1940 to 81%. During World War II, the top rate came close to 100%.

FDR’s thinking is best reflected in his message to Congress on April 27, 1942: “Discrepancies between low personal incomes and very high personal incomes should be lessened; and I therefore believe that in time of this grave national danger, when all excess income should go to win the war, no American citizen ought to have a net income, after he has paid his taxes, of more than $25,000 a year.” A 100% tax on net income above $25,000—equivalent to more than $1,000,000 today—was to be implemented, not only on salaries, but on all income sources, including interest from tax exempt securities. Congress found 100% to be slightly excessive and instead settled on a top marginal income tax rate of 94%. It also enacted a mechanism that limited the average tax rate, so that in practice taxes paid could not exceed 90% of income.

Seventy years prior, during a Civil War in which 620,000 soldiers died (about as many as all US deaths during the two world wars, the Korean, Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan wars combined), the debate about how to tax the wealthy had involved rates between 0% and 10%. Now the question was whether 90% or 100% was more appropriate—proof if need be that the rise in tax progressivity had more to do with the political changes of the early twentieth century than with the necessities of war. From 1944 to 1981, the top marginal income tax rate would average 81%.

These quasi-confiscatory top tax rates applied to extraordinarily high incomes only, the equivalent of more than several million dollars today. In 1944, for example, the top marginal tax rate of 94% started biting above $200,000, the equivalent of ninety-two times the average national income per adult, or more than $6 million today. For incomes above $1.2 million in today’s dollars, tax rates in a range of 72% to 94% still applied. But below that level, taxation was in line with what’s typical nowadays. Incomes in the hundreds of thousands of today’s dollars were taxed at marginal rates in a range of 25% to 50%.

Ever since the Civil War, the opponents of progressive taxation have found it an effective strategy to pretend that the middle class is hit by taxes that only concern the ultra-wealthy. But nobody except the ultra-rich was ever subjected to America’s confiscatory top tax rate policy. The upper middle class certainly never was.

As Roosevelt’s message to Congress expresses clearly, the quasi-confiscatory top marginal income tax rates championed by the United States were designed to reduce inequality, not to collect revenue. Why would anyone try to earn more than a million dollars if all of that extra income went to the IRS? No employment contract with a salary above a million would ever be signed. Nobody would amass enough wealth to receive more than a million in annual capital income. The rich would stop saving after they reached that point. They most likely would give their assets to heirs or charities once they surpassed the threshold. As such, the goal of Roosevelt’s policy was obvious: reduce the inequality of pre-tax income. The United States, for almost half a century, came as close as any democratic country ever has to imposing a legal maximum income.

High Top Tax Rates, Low Inequality

The justification for continuing the FDR-era policy has always been that sky-high incomes are, for the most part, earned at the expense of the rest of society. This is obviously the case during wars, when arms dealers flourish as the masses fight. But it can be equally true in peacetime whenever income at the top of the pyramid derives from exploiting monopoly positions, natural resources rents, power imbalances, ignorance, political favors, or other zero-sum economic activities (we’ll study one of these, the tax-dodging industry, in the next chapter). In such cases, confiscatory top marginal income tax rates do not reduce the size of the economic pie; they simply reduce the size of the slice that goes to the wealthy, increasing income for the rest of the community one for one22.

We can, of course, debate the merits and demerits of this view, and whether it might make sense to return to 90% top marginal income tax rates today, an idea we’ll discuss in Chapter 8. But to start thinking about such a proposal, we must first address a basic question: Did FDR’s tax policy work? Did it really reduce the concentration of pre-tax income?

There is one indication that it did: from the 1940s to the 1970s, very few taxpayers reported gigantic incomes to the IRS. Only a few hundred families showed up in the top tax brackets subject to the confiscatory rates. The inequality of fiscal income—that is, income as reported to the tax authority—collapsed. The share of fiscal income earned by the top 0.01% reached a historical nadir in the postwar decades. From the creation of the income tax in 1913 to FDR’s inauguration in 1933, this group earned on average 2.6% of all fiscal income each year. From 1950 to 1980, that number fell to 0.6% on average23. Looking at tax data, there is no doubt that Roosevelt’s policy achieved its goal.

But what if tax data are misleading? It is possible, after all, that the wealthy found ways to shelter income out of sight of the IRS. Maybe they used legal or illegal tricks to dodge the top marginal tax rates. If we push this line of thought to the extreme, it’s possible to imagine that inequality never really fell in the United States, or at least not nearly as much as suggested by tax statistics. What if the massive swings in the share of fiscal income going to the top groups are an illusion caused by tax avoidance?

It would be a mistake to dismiss this argument out of hand. As a theory it has intuitive appeal: when top marginal tax rates are high, it seems plausible that the affluent will seek to hide income. If they were successful, then inequality might not have declined much. Important economic phenomena—like how much inequality there is—rarely reveal themselves effortlessly; they must be patiently and scientifically constructed, and no science is definitive. The best way to measure inequality involves tracking all forms of income, including income that does not have to be reported to the IRS, such as profits kept within firms, interest earned from tax-exempt bonds, and so on. In other words, we must distribute the totality of national income to the various groups of the distribution, as we did in the previous chapter for more recent years.

The picture that emerges from this exercise corroborates, for the most part, what fiscal income data suggest. The inequality of national income truly fell from the 1930s to the 1970s, during the period when exorbitant incomes where taxed at quasi-confiscatory rates. The decline is a bit less spectacular than what a simple reading of the income tax statistics would suggest, mostly because corporate retained earnings rose in the postwar decades, to reach about 6% of national income in the 1960s. When profits are not distributed, they do not show up on the individual income tax returns of shareholders, and can thus lead observers to underestimate how much inequality there really is. When they were subject to individual tax rates as high as 91%, some wealthy shareholders instructed their companies to reinvest their profits (free of individual income taxation) instead of paying dividends (which were subject to the individual income tax).

But even after accounting for retained earnings and all other forms of untaxed income, income concentration did fall dramatically from the 1930s to the 1970s24. The share of America’s total pre-tax national income earned by the top 0.01% declined from more than 4% on the eve of the Great Depression to 1.3% in 1975, its lowest level ever recorded. Yes, some profits were kept tax-free within firms, but these sums were not as large as one might think. Retained earnings were sizable in the 1960s (6% of national income), but not incommensurate with what’s been typical in the long run—for example, corporate retained earnings have amounted to 5% of national income since the turn of the twenty-first century. The reasons retained earnings were not much larger when dividend tax rates were higher are multifold. Dividend distribution policies are sticky: once a mature business starts to distribute dividends to shareholders it rarely reverses course, unless the business is close to bankruptcy. General Electric, DuPont, Exxon and other corporate behemoths did pay large dividends after World War II. Shareholders prefer earning cash to letting profits sit within big companies, because there is always a risk that corporate managers will dissipate undistributed profits with dubious investments. High undistributed profits also give ammunition to unions—which were powerful in the 1950s and 1960s—to ask for wage increases.

Overall, there is no indication that under the presidencies of Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower the wealthy were rich in ways that fiscal data massively underestimate. And indeed, to anybody alive in the 1950s, it was clear that the world, for the rich, had changed—and not in good a way. In 1955, Fortune magazine ran an article titled “How Top Executives Live.”25 It is a heartbreaking read. “The successful American executive gets up early—about 7:00 A.M.—eats a large breakfast, and rushes to his office by train or auto. . . . If he is a top executive he lives on an economic scale not too different from that of the man on the next-lower income rung.” How come? “Twenty-five years have altered the executive way of life noticeably; in 1930 the average businessman had been buffeted by the economic storms but he had not yet been battered by the income tax. The executive still led a life ornamented by expensive adjuncts that other men could not begin to afford. . . . The executive’s home today is likely to be unpretentious and relatively small—perhaps seven rooms and two and a half baths.” Worse yet, “the large yacht has also foundered in the sea of progressive taxation. In 1930, Fred Fisher, Walter Briggs, and Alfred P. Sloan cruised around in vessels 235 feet long; J. P. Morgan had just built his fourth Corsair (343 feet). Today, seventy-five feet is considered a lot of yacht.”

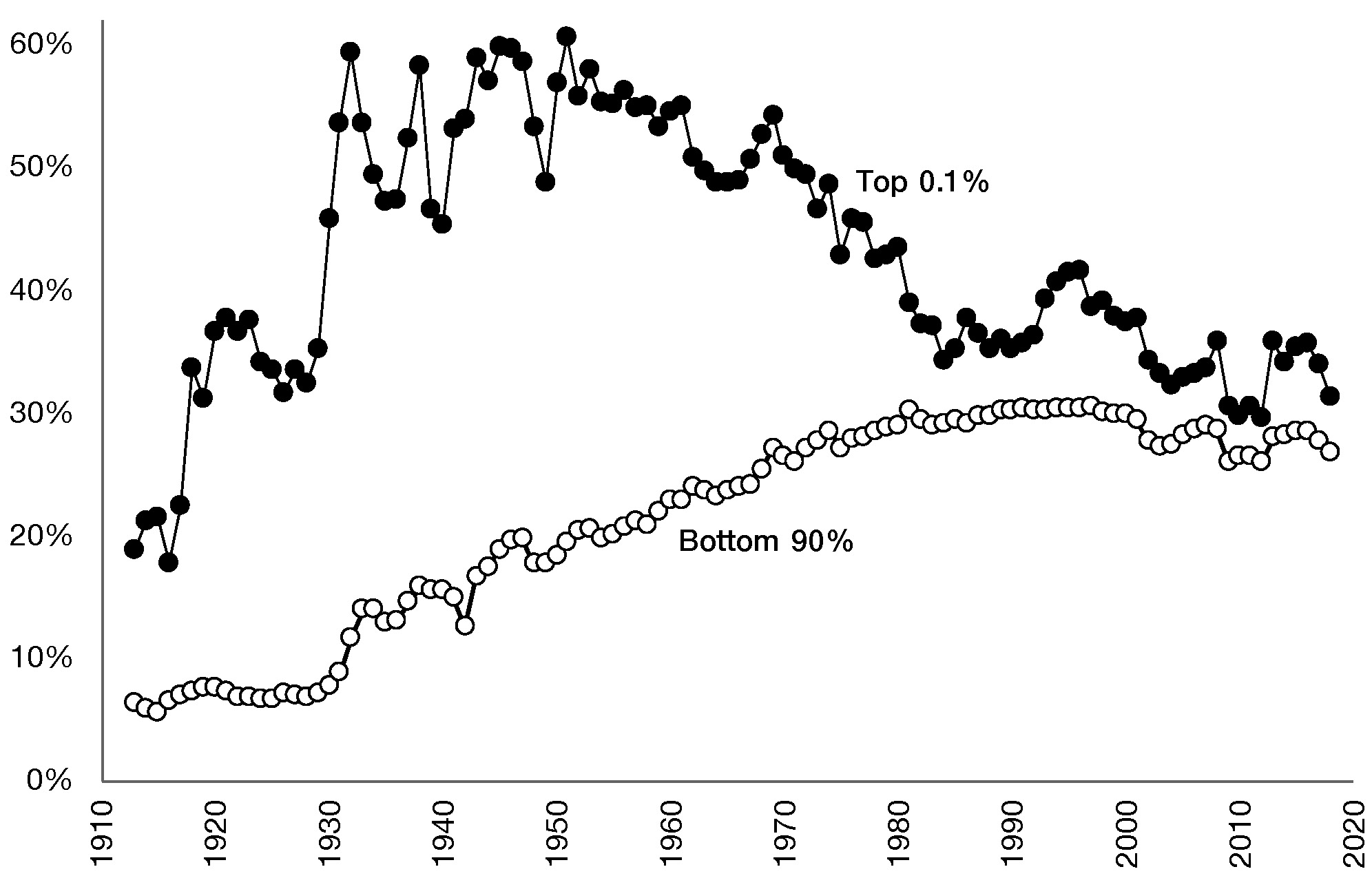

The Average Tax Rate for the Rich under Eisenhower: 55% Not only did the wealthy see their incomes constrained, but on their reduced income they paid high effective tax rates.

Figure 2.2 shows the effective tax rate paid by the top 0.1% highest income earners since 1913, including all taxes paid at all levels of government. Today, as we have seen, America’s tax system is mostly a giant flat tax: the most fortunate barely pay more than the middle class (and in fact pay less, the closer you get to the top). Half a century ago, things looked quite different. Working-class and middle-class Americans paid less than today, because payroll taxes were lower. The rich, on the other hand, paid much more. For forty years, from the 1930s to the 1970s, the wealthy paid more than 50% of their income in taxes, three times more than Americans in the bottom 90% of the income distribution. The average tax rate of the top 0.1% culminated at 60% in the early 1950s and remained around 55% during Eisenhower’s two terms. Over this period the US tax system was undeniably progressive.

How were these high effective tax rates achieved?

First, by keeping tax avoidance in check. In the next chapter we’ll explore how tax avoidance has changed over the last century. But what’s important to realize already at this stage is that letting people or corporations dodge taxes is largely a choice that governments make. In the postwar decades, policymakers chose to fight avoidance and evasion; we’ll soon see how.

But the more fundamental reason why the US tax system was so progressive is because of heavy taxes on corporate profits. In all capitalist societies, the richest people derive most of their income from shares, the ownership of corporations—the true economic and social power. When corporate profits are taxed stiffly, the affluent are made to contribute to the public coffers. That’s true even when companies are instructed to limit their payments of dividends, because the corporate tax is on profits before reinvestment or dividend disbursements. In effect, the corporate tax serves as a minimum tax on the affluent.

From 1951 to 1978, the statutory rate of tax on corporate profits ranged from 48% to 52%. In contrast to the top-end individual income tax rates, these rates applied to all profits. They were not marginal rates designed to deter rent-seeking and curb excessive incomes. They were flat rates meant to generate revenue. And generate revenue they did. In the 1950s and early 1960s, corporate profits were effectively taxed at rates approaching 50%. For any dollar of profit made in America, half went straight to government.

As we can see, it’s through the corporate income tax—more than through the individual income tax—that the very rich contributed to the public coffers in the middle of the twentieth century. By design, few people were in the top individual income tax bracket where the top marginal tax rates of 90% applied. But essentially all shareholders faced 50% effective tax rates on their share of a firm’s profits. In the postwar decades, the ownership of corporations was still highly concentrated in a few hands (this was before pension plans somewhat broadened equity ownership) and firms were highly profitable, so firm owners earned a lot of income. Companies paid half of their profits in tax straight to the IRS. On whatever remained after cutting that check, many firms paid dividends to their shareholders, and these dividends were taxed at rates as high as 90%.

Does that look like the policy of a country that doesn’t care about taxing the rich?

Footnotes:

1 The top marginal income tax rate even reached 92% in 1952 and 1953.

2 The property tax records from colonies have been used by scholars to construct inequality statistics for antebellum America. Northern colonies had levels of inequality substantially lower than in England (Lindert, 2000).

3 Einhorn (2006).

4 Einhorn (2006).

5 This saying is attributed to John Steinbeck by Canadian author Ronald Wright (Wright, 2004) but is likely a paraphrase.

6 The Revenue Act of 1861 established the first federal income tax with a rate of 3% for incomes over $800 but it lacked an enforcement mechanism and was never applied. It was repealed and superseded by the Revenue Act of 1862.

7 In 1860 there were about 31 million inhabitants in the continental United States (US Bureau of the Census, 1949, series B2). The national income of the United States was about 5 billion current US dollars (the Historical Statistics of the United States report a total “private production income” of $4.1 billion in 1859 in series A154, which is likely to be slightly on the low end and must be adjusted upward for the small amount of government production), and hence average income per capita was around $150 in 1860, i.e., a fourth of the exemption threshold of $600. From 1860 to 1864 the price index increases by about 75% (Atack and Passell, 1994, p. 367, Table 13.5), so the average income per capita reached about $250 in 1864.

8 Huret (2014), p. 25.

9 The price index was multiplied by a factor of about forty between 1860 and 1864 in the Confederacy but increased only by about 75% in the Union. Confederacy: Lerner (1955); Union: Atack and Passell (1994), p. 367, Table 13.5.

10 Huret (2014, p. 40– 41).

11 US Bureau of the Census (1975), series Y353– 354.

12 Holmes (1893).

13 Sparh (1896), Pomeroy (1896), and Gallman (1969).

14 Lindert (2000).

15 Seligman (1894).

16 Huret (2014), p. 85.

17 See Mehrotra (2013) and Scheve and Stasavage (2017).

18 According to available estimates, the top 10% owned 90% of total wealth in Europe on the eve of World War I, against about 75% in the United States (Piketty, 2014; Piketty and Zucman 2015).

19 Fisher (1919).

20 Einhorn (2006), Chapter 6.

21 Plagge, Scheve, and Stasavage (2011), p. 14.

22 See Piketty, Saez, and Stancheva (2014) for presenting such a theoretical model and estimating it using modern data.

23 Kuznets (1953) pioneered the creation of top income shares using individual income tax statistics. See Piketty and Saez (2003) for modern estimates of top fiscal income shares. The statistics cited here refer to the top 0.01% income share excluding capital gains.

24 For a detailed description of how we account for untaxed income, and complete results, see Piketty, Saez, and Zucman (2018).

25 Norton- Taylor (1955).