Colombia’s President Iván Duque came to power two years ago on a neoliberal, pro-business agenda, promising more jobs and less taxes. His decision to break that promise two weeks ago couldn’t have come at a worse time: in the middle of a mortal pandemic that has hit Colombia harder than virtually any other country in the region. Duque proposed raising the sales tax, a form of taxation that most negatively impacts those with the least money to spend. The tax reforms are part of a broader “paquetazo neoliberal,” or “neoliberal package,” which also includes changes to the pension system, the healthcare system, and the labor code, all of which, if implemented, would put a greater squeeze on struggling Colombians.

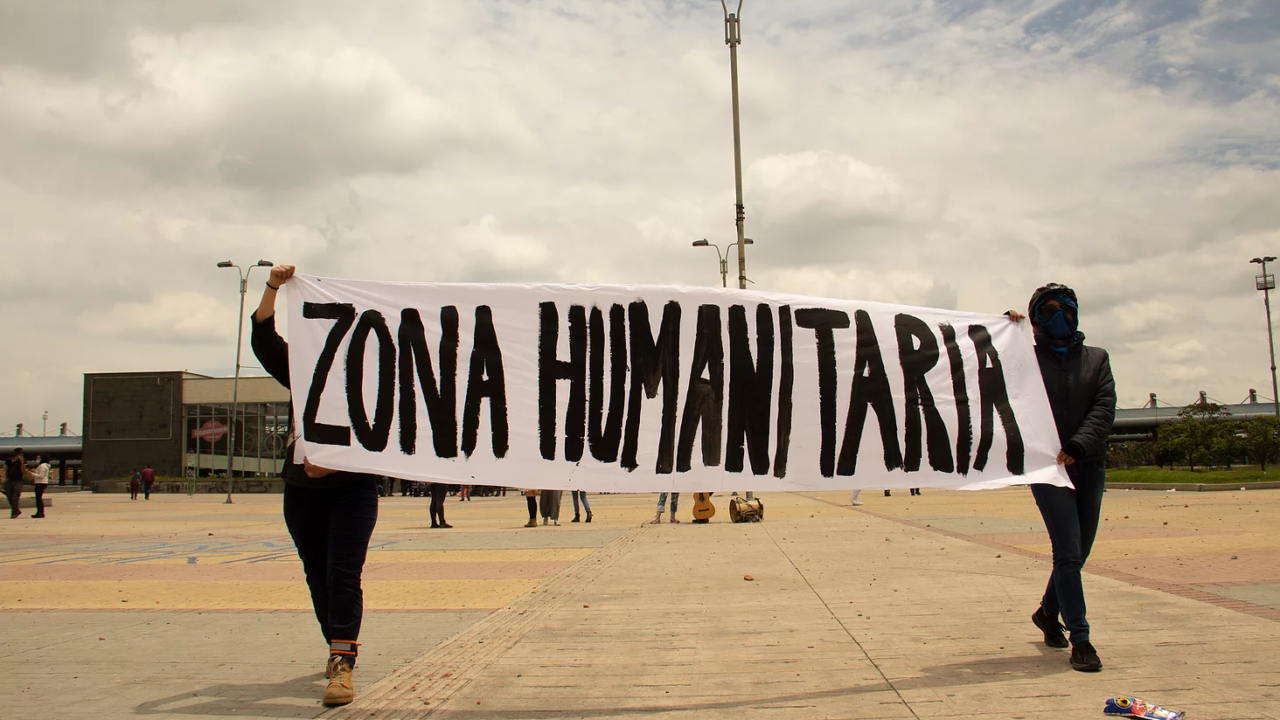

The people’s response to the “tax reform” was massive and decisive. A coalition of unions and civic organizations called for a national strike on Wednesday, April 28, and hundreds of thousands of people from across Colombia poured into the streets. By Sunday, truck drivers had joined the strike, a move that forced Duque to withdraw the tax, and the Minister of Finance who authored it resigned. The government’s reversal was a victory for Colombians, but the strike continues. In response, the government has deployed the national police, the army, riot cops, and vigilantes, aiming to stop the mobilizations by brutalizing the population. Multiple videos show uniformed and non-uniformed police utilizing live ammunition against protesters in broad daylight. Cali has been the epicenter of the discontent, and the city that has borne the brunt of the government’s military response.

Nathali Pareja is a human rights observer in Colombia. An independent human rights report indicates that, two weeks into the strike, there were 362 victims of physical violence by police, 39 people killed by the state, 1,055 arbitrary detentions, thirty victims of ocular trauma, 133 cases of shotings, and 16 victims of sexual violence. This is only a preliminary report, which does not take into account the more than one hundred people who are reported missing. On May 7, I talked with Pareja about the human rights violations taking place across the country right now, why the demonstrations continue, and the path ahead for Colombians. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Tell us about your work.

I am part of an organized group of soccer fans from a professional soccer club, America de Cali. The fans are known as “Barra Baron Rojo Sur.” Baron Rojo has a committee called the Human Rights Committee Juan Sebastian Tenorio Bernal — named after Tenrorio Bernal, a young man from the Baron Rojo who was murdered by the paramilitaries in one of our trips to support the team. We call ourselves Human Rights Defenders. Our work is to observe and to document human rights abuses.

Is it common for soccer fans to organize politically in Colombia?

Organized soccer fans inhabit a microworld. So there are those who think of themselves politically, those who think of themselves socially, and those who just want to buy wine or encourage the team. But this time around, we have reached such levels of frustration in this country that most soccer fans are currently fighting in the streets because we can’t say it’s only Baron Rojo Sur.

Here in Cali, before the strike, there was a war against the Radical Front, which is the fan base from the other professional Cali team, Deportivo Cali. There was a war between the two sides. There were deaths every day, from one side or from the other. The day the strike started, one of the leaders stood up and said, “Today, we are not going to kill ourselves for the colors, but if we have to kill ourselves, we are going to do it for the country.” It’s a very big deal, truly.

Are there any reliable figures on the number of dead or missing people?

We have some tentative numbers. The police have not allowed us to access the real numbers. We have, for example, 28 people reported dead in Cali, one week into the strike — and that is only in Cali. We have just been informed of two places where trucks full of people in civilian clothes arrived to shoot [protestors] in broad daylight. Inside [the truck,] there were weapons and implements identified as belonging to the national police.

It is impossible to count [the injured]. Here in Cali, if I were to say two hundred injured a day, that would be too little. But the most worrying issue is the people who don’t show up. We have reports of people being taken to places of detention but we can’t find them. We have reports of more than two hundred people disappeared. We are not able to verify this information because the police are [not] systematizing the information nor are they allowing us to access the medical posts, the police stations, or anything.

People are not going to the hospitals because the police are at all the doors, detaining people who arrive injured. So each resistance post is trying to form health brigades to care for comrades who get injured. And we have another aggravating factor: the prosecutor’s office, the one in charge of picking up the people who die, has not come to pick them up.

Some images of the repression show police and civilians shooting people at point blank range in the middle of the day, without fear of retaliation.

There are people wearing civilian clothes who are later proven to be from the national police. However, there are also people organized in paramilitary groups saying that they have the weapons, they have the manpower, and they are going to get rid of the young people who are fighting for a better future. The police incentivize the [paramilitary groups] to do it. That is very disturbing. Moreover, Mr. Alvaro Uribe [former president and member of the governing party], is calling on people to arm themselves, defend their supposed right to be able to move about, go buy stuff, leave their homes.

The mobilization beat the government’s proposal to raise the sales tax. The Finance Minister also resigned. However, it seems people want more, particularly in your city.

What has been achieved so far is that the tax reform is withdrawn from the chambers of Congress. But what they say is that they are going to review it. So that’s a partial win. It’s not a real triumph because the tax reform is going to be put back in; they’re just going to try to soften it up a little. The health reform, the pension reform, and the labor reform are still moving forward.

This is the continuation of a movement that started in November 2019. Chile was going through a similar process: people rebelling against an economic trickle down that never happened. Do the people fighting in Colombia see their fight as one against neoliberalism?

No. We have not reached that point. And we did not get to that point because of the level of disorganization. Every organization on the left pulls for its own side. There is an infinite level of disunity. What’s happening here today is a people’s uprising. But Colombians are disorganized and adaptable to their living conditions. We raised the issue of the price of eggs because that is what people eat. If they mess with the price of eggs, people go out into the streets. That was what really happened.

This social uprising helps us begin to organize ourselves, to return to the issue of social and popular organization. That is what all the organizations, parties, and movements of the left are trying to do. We are betting to see growth. But it’s not the end of neoliberalism yet, no.

How is this resolved in the short term?

At this moment, [there is] a lot of pain for the young people, the dead people. In terms of the issues people are raising in the territories, it’s very broad stuff. Some want President Duque to resign. Others propose dialogue that could lead to substantial agreements. But for the movement right now, a minimum requirement should be the withdrawal of all the reform proposals.

Is there anything else people in the United States should know about what is happening in Colombia right now?

Something that has shocked us is the violence taking place during night. At night, a special police group called GOES arrives with the purpose of shooting people. That is how the highest number of dead has fallen. We are particularly concerned about what happened at two points of resistance, called La Luna and La Portada, where men in civilian clothes arrived in a truck, hiding their police identification, shooting, leaving two dead. That worries us greatly, and it worries us because the state, instead of trying to de-escalate the military route, the use of arms, is shamelessly bringing them out into the open. That makes the human rights issue so much worse.

The situation has overwhelmed the organizations that were covering [human rights issues] in Cali; we cannot cope. We are at a very high level of physical and moral exhaustion because, in many places, we have also been attacked by the police; if they attack us, they will obviously not respect the people. We are very concerned about the state, but we are concerned about the para-state as well.

Are you afraid for your life?

Well, the normal fear of going out and getting shot

Most organizers in the world are not concerned about getting killed. You seem to see it as just another hazard of the trade

The problem is that you normalize it, but it is not normal. It is not normal that when we go out on the street, we prefer not to wear our human rights ID cards or vests because we are afraid of being attacked. But here there is a saying: “He who is afraid should buy a dog.” I have three.