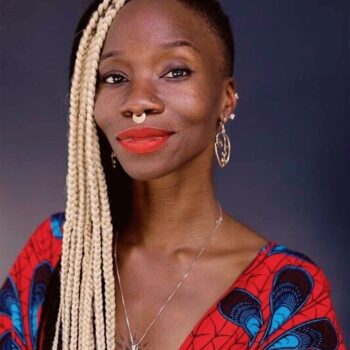

Black Visions co-executive directors Miski Noor and Kandace Montgomery sat down with Denise Perry, the executive director of Black Organizing for Leadership and Dignity (BOLD); Adaku Utah, the organizing director of the National Network of Abortion Funds, the co-director of Harriet’s Apothecary, and a teacher with BOLD; and Prentis Hemphill, the founder and director of the Embodiment Institute and a trainer with BOLD. They talk about the centrality of care, the importance of taking risks and making mistakes, and what it means to invest in Black leadership in this moment. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Kandace Montgomery: What is your vision for safety that would replace policing and imprisonment?

Adaku Utah: I often begin with just centering our inherent value and worth. So many of the practices that move towards violence and harm come from a devaluing of humanity. And so really grounding our vision in the root of: all of us have inherent worth and value, not because of what we produce but because of who we are. A huge part of the vision is a willingness to turn and face how harm lives inside of us, both the ways that generational violence and trauma informs what we know and feel is possible around safety, and also how we produce harm.

That takes time and commitment. I don’t know any relationship that does not require work. We’re not perfect people, and we will make mistakes that potentially harm one another, so can we choose to keep returning to each other in ways that are generative and not producing more harm? Something that keeps coming up for me inside of this is making enough spaciousness for us to not throw each other away when we fail, using those opportunities as lessons for how we might be better with each other.

Prentis Hemphill: It really strikes me that care is so far removed from the thing that we organize our structures or institutions or even our relationships around. There’s transaction, there’s extraction, there’s punishment. Care sounds nice, but what would it really mean if that was the center of everything you built? How would it actually look? I think it would lead us to radically resourcing our communities in ways that we haven’t seen. The piece about the risk of it all doesn’t feel small to me — that for us to create more safety, it’s going to feel like a bunch of different risks that we have to take. Risks to intervene, risks to be accountable, risks to say how we feel. That’s actually the skill that we have to be developing in this moment.

KM: Yeah, folks are there with us one hundred percent around housing, around food, around healthcare, around jobs, around culture, around youth programming, whatever it is, but there’s that fear of taking the risk of trying out something new. And we’re in this place where we have to say, well, which risk is worth taking? How do we actually talk to our folks to move through those real things that we’re going to face as we move this vision forward?

Miski Noor: Let’s talk about the relationship between movements and infrastructure. What did the uprisings last year show you about where our movement is weak and where we are strong?

Denise Perry: The question for me is where we choose to invest. How do we ensure that our organizations are making an investment in [people]? It’s a real fine dance between the organization and the people in the organization; they’re in service to each other. Those folks are in service to building power through an organization and that organization’s responsible to building power in those people.

I also think that we need to be honest with each other and allow people to make mistakes. As the energy lifts and tensions rise, we have to give room for people to make mistakes. And when we don’t, we stop everything because it tears trust, it holds people back, and we don’t have the numbers that we can afford to just be like, okay, well they’re not doing it exactly right, so leave them on the curb and let’s keep going. We don’t have that kind of power at this point.

And also it’s whack. That is the antithesis of what we’re trying to do. We’re trying to bring everyone into something new. Something that would serve us all is to see people in their humanity, to see people and support their dignity. Mistakes happen because people take risks and risks are taken because that’s what we see as an opportunity to step into and make something happen.

PH: One of the things I witnessed this past year was like, oh, we have a way to claim the future, to name what it is that we want. We’re going to make this massive intervention that’s going to be beyond what [some people’s] imaginations have even allowed them to see, and we’re going to do it in a way that is grounded in our love of our communities, grounded in our organizing work, grounded in our radical visions. So that’s one of the lessons over this last year: just say what we mean. [It was] a huge, huge gift and a lesson for me; it changed everything.

You all have put out this vision [of abolition]; what does it take for us to do this emotionally, relationally? How do we do this? How do we build the capacity internally to live into these visions? Grace, accountability, forgiveness are skill sets that we need to develop in order to live inside of that vision. There’s a choice we can make between a movement that is centered around care and transformation and accountability and a movement that is centered around vengefulness and division. And I think we’re at a critical choice point.

AU: Can we spend more time really investing in the quality of how our people lead and organize before pushing them into roles of leadership? When we hear that our people are tired, how can we listen to that and shift the pace of work? I long for more shared leadership that moves in like a relay race, where we just keep passing the baton because our bodies move through these cycles on a daily basis of motion and rest, motion and rest, motion and rest. And I think sometimes we either don’t listen to it or take advantage of it, and I long for a structure that is malleable enough to hold different kinds of pace that helps us sustain our people.

MN: How does philanthropy fit into this puzzle? What are your dreams or visions around the kind of models that are necessary for the world that we’re trying to build?

DP: Money is flowing right now, but it is not taking on any sort of new orientation. So, maybe I don’t have to write a proposal in order to get the money and maybe I don’t have to write a report, but it doesn’t fundamentally address the challenges. And I know I’m speaking super generally and there are family foundations that do things much differently, and I am excited about that. I think those are the places that are really trying to model something different. And I think that is critical and that is the best source for what we’re up to, but it’s also minimum.

The thing is: how do we organize the money rather than the money organizing us? Because right now, they are organizing us. They got us dancing out here in all kinds of ways. And it’s like, this is our money. This is our money, we made every penny that you have to give away, every penny. And so when I shift my orientation to the fact of like, you owe me my money, it’s not about what am I going to do for you to get my money back, it’s: when are you going to write me my check? And I think if we can be that bold about it, then it begins to open up the opportunity for us to organize the money versus the money organizing us.

PH: Now that we see like, oh, you got all these resources up in here, philanthropy? Well, we need some land. Okay, we need some buildings; we need some things that are going to last us over time. The flavor of our demands can also shift to be long term.

DP: The church, they always had a building. And it allows you to be stable; it allows you to focus on the work. My old organization, we moved three times and it impacts so much because you want to be a part of the community, and it’s really hard to do if you don’t have a stable location. And I think the church proved that.

I never worked for a local union that did not own their own building. And they made those investments over time. And in some instances when they got into financial struggles, it was because they had those buildings to help keep them moving. The increase of our growth and stability and connection and community, the blending of service and power building, all of that becomes so much more possible when we are rooted.

KM: I’ll tell you, 97 percent of the thirty million [that Black Visions raised last summer] came from individuals. Philanthropy came in under less than five million. And the money that we raised is less than five percent of what philanthropy sits on every single year. It’s actually pennies in the bucket of what’s really out here for resources.

And then, how do we tap into ourselves to be able to navigate that? I grew up poor. We didn’t always have food in the fridge, I didn’t have a family member who had more than $1,000 in their bank account at any one time. And so, for both of us, to be in positions where we’re literally stewarding millions of dollars and trying to do that in a value set that is different than how we were taught to think about money, all in real time, all while people are moving through a pandemic, that’s hard.

But how do we forecast some of that too, and build our strategies around that? White people will just throw money in moments of crisis, and we have to actually be preparing our folks to think about, how do we navigate that with our values at the core? Black Visions, we really had to learn that. I had to grow so much. Miski and I always talk about like, we didn’t sign up to be multi-million dollar organization EDs. I had to learn a bunch of stuff, like spreadsheets in Excel and financial infrastructure and red tape and bureaucracy. But I think the hardest growth was really the ways that shame and imposter syndrome and being afraid of messing up, how much I saw that dictating whether or not I was able to be strategic and to really center care in my relationships. And that was actually the biggest growth edge and what made last year the hardest year of my life to date.

KM: What do all of you do to make movement work more sustainable for you? How do you keep self-care at the center of radical transformation?

AU: For me, as a dark-skinned, queer, non-binary migrant, before I was even an atom in my mother’s womb, there were so many expectations placed on me of what kind of power I have and how my body needed to be in service to other people’s lives. And it is a constant practice to keep reclaiming that. I love Black people, I’m in a deep commitment to reshaping our movements and building power and love and joy with our people, and I also know that the work of care, the work of organizing, teaching healing in this time, that leads to me overworking.

I also come from Nigerian parents who grew up during the war where it’s expected that you work really, really hard and produce at an excellent and high level. And I love being excellent and I am excellent — and I want to do that in a way that doesn’t cause my body harm. And so it’s a constant assessment of, can I keep coming back to this home? I really appreciate the ecosystem of care that’s around me, that also includes my ancestors who I pray to every day. And that helps me stay really close to this North Star of liberation and also softened enough to feel the impact of this work on my body.

In a practical way, some things that I want to highlight within the work that I’m doing within National Network of Abortion Funds, we deeply invested in our leadership development and organizational development in a way that feels more holistic than I’ve ever experienced. Our leadership development programs hold these six core competencies that we’re building: purpose and commitment, political analysis, strategy and action, reflection and humility, and self and community care. And these core competencies didn’t just come out of thin air, they came from our members really talking about, what does it mean to sustain ourselves at the scale of winning, and what kinds of relationships do we need to be building? What kinds of skills?

We also shifted our work schedule to a 32-hour work week. I really believe that movement building doesn’t only happen within the work that we’re doing in organizations; it also happens with how we’re building relationships with our families and our communities, and we need time to do that and not just be on the grind within nonprofits but also tending to the relationships that we have outside of our places of employment.

And then the other thing that we did this year in particular was intentionally creating spaces of connection that were not just tethered to a campaign but were just about love and joy. And literally they were called joy spaces that our staff and members co-created, where people could love up on each other.

PH: This question actually feels really hard for me. As someone who’s been doing practitioner support work, it can feel really challenging for me to figure out how to attend to myself. So I guess I just mostly want to be honest that it feels like a thing that I’m navigating all the time. And I think that the things that I have learned and have worked really well for me are that I have a life adjacent to and outside of movement spaces that feels full and nourishing. It has been the relationships, my home, that has always fed me. I grow things, I love people, I love all the things that grow around me, I am working to take time off.

And then having people that are further down the road that are in my life now that I can hit up like Denise Perry and be like, “Denise, I’m raggedy, what’s up? How do you do it?” Because I called Denise and she’s like, “I’m riding my bike through Miami.” And I’m like, “Damn, okay.” I need to step my game up.

DP: One place that I really get a lot of juice is just staying in relationship with folks who are out here doing the work, and from time to time could use somebody to acknowledge their presence, acknowledge their struggle. And it’s not anything more than that, right? Sometimes it’s a text message but knowing that it’s keeping me connected and it’s in service of things I believe in and more importantly in relationship with people I really deeply care a lot about — and sometimes worry a little bit about.

MN: What is being said but remains unheard?

DP: Change and transition is hard; it’s not magic. It’s hard, it’s life, and it can be a little messy.

PH: Care, accountability, risk over comfort. Partly what we’re moving towards is not just being comfortable but to be really in our lives and the grief and the beauty and the love and the sorrow, and to not have a disproportionate amount but to be able to really live our lives. And so let’s step into what’s hard as much as we step into what’s beautiful.

DP: Ooh, I sign up for that.

AU: We are worth changing for. I want to change for you all. Each of you are worth changing for, my nibbling is worth changing for, the folks that I organize with are worth changing for, and that even in the hardness and contradiction of it, it is worth it because of us and it’s how we love. It’s actually an extension of love.