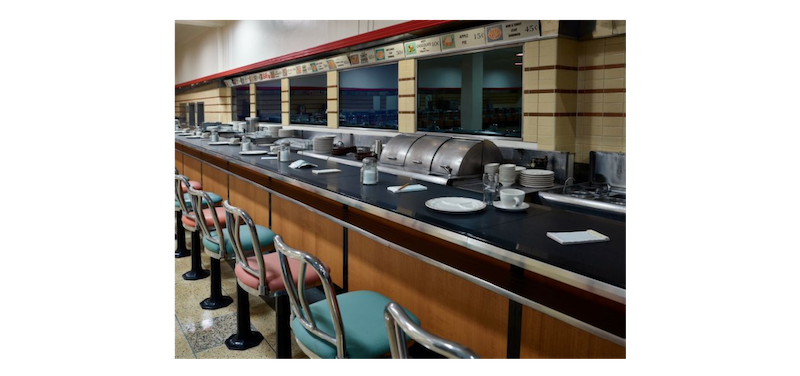

On February 1, 1960, four students from North Carolina A&T — Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair, Jr, and David Richmond — sat in at the Greensboro Woolworth’s counter and demanded service. They fully expected to be arrested and had enlisted the help of a local white businessman to alert the press. They were refused service, but the police also refused to arrest them, as they were not being aggressive. The next day, 20 students arrived to occupy half the lunch counter. They were refused again. The numbers tripled by the third day. By day four, 300 students occupied the Woolworth’s until closing despite facing off with 50 agitated white people who had occupied the restaurant first, threatening the protestors. But the students were undeterred. The Greensboro Four called for a mass meeting on February 6. Fourteen-hundred people attended; one thousand of them headed to Woolworth’s after.

News from Greensboro captured the popular imagination, and the sit-in movement spread like wildfire. By the middle of the second week, activists from a dozen cities in North Carolina had joined, and the movement soon spread to Virginia and Tennessee. In Nashville, Rev. James Lawson had been training activists for a sit-in for the past six months. When the Nashville sit-in movement launched, the highly disciplined organizers won the first lunch-counter desegregation in the South. The Greensboro students won that summer. All told, over 70,000 people participated in the sit-in movement, winning integration in some 100 cities.

The sit-ins may have spread like wildfire in the winter of 1960, but neither the tactic nor the undergirding infrastructure were particularly new. Starting in the early 1950s, local movement centers had begun developing in the South, most of them church connected and, largely, church financed. Montgomery, Alabama, is the most widely known, but there were also centers in Birmingham, Baton Rouge, Nashville, and Petersburg, Virginia, among other places. During the first few weeks of sit-in activity in early 1960, organizers from these centers helped spread the tactic by contacting student leaders around the South and by providing bail funds, meeting places, and contacts with adults experienced in nonviolence as ideology and practice. The support of these older activists was important in part because the students faced repercussions from Black colleges, which were dependent on white economic or political support. Dr. King was among the adults involved in furthering the spread of the movement, as were Fred Shuttlesworth of Birmingham, Wyatt Tee Walker of Petersburg, and Floyd McKissick of North Carolina. Students also set up their own infrastructure, which took a different shape in each location. Some took over campus NAACP chapters; others organized through student government or some other campus office.

The most amazing thing about the sit-in movement is that it was largely spontaneous but managed to reinvigorate the civil rights movement across the South, leading to the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Freedom Rides, and dozens of other campaigns. In short, the small group of organizers who launched the sit-in movement created a ruptural moment. They did it through bold and persistent action that captivated the attention of others, who then launched copycat actions or helped to undergird the initial movement.

The spontaneity and courage of the sit-in movement create some clear lessons for us today. Some of the most salient are:

-

Taking bold action is imperative; the plan does not have to be perfect. Four students in Greensboro launched a massive movement; they made a plan and took action. It didn’t matter that they were small in number or that they were treated with benign neglect when they first sat in; they tried something. A similar analogy is Greta Thunberg’s one-person stand for climate at the Swedish Parliament. The weekly school strike that she started turned into millions participating in Fridays for our Future. Starting with small numbers does not necessarily mean the scale will always be small or the action won’t be bold.

-

Disruptive action takes persistence; it might not end in hours or even days. We do not determine the success or failure of an organizing campaign in a few hours, so why do we think that way about disruptive actions? The key to Greensboro was that the organizers came back day after day, bringing more and more folks each time.

-

Counter-reaction, while painful, helps propel a movement’s success. The success of much of the Civil Rights Movement was due to the simplicity of what protestors were doing — riding a bus, eating at a lunch counter — and the ferocity of the system that opposed them. If Woolworth’s had continued to ignore the participants, the movement would not have gotten the conflict it needed to galvanize others to take action or effectively push against the system of segregation. When white supremacists came to harass the students and the police came to arrest them, the sit-ins became newsworthy. Of course, the organizers ensured that there would be confrontation by filling the lunch counter. Four students could be ignored, but 60 could not.

-

Real mass movements are organic and cannot be controlled. Some organizers were slightly critical of the Greensboro protagonists. Mary King, longtime SNCC activist and Director of the James Lawson Institute, recalled, “Those students in Greensboro didn’t even know the term sit-in.” Yet the Greensboro sit-ins were the catalyst that led the Nashville sit-ins to deploy. They also sparked sit-ins throughout North Carolina, Virginia, and the rest of the South. There was no central command and control; student leaders did not convene until Ella Baker brought them together over Easter Weekend at Shaw University.

-

Making the tactic replicable and the demand universal helps with achieving scale. Almost all cities and towns had restaurants with lunch counters where sit-ins could occur. The sit-in movement, while requiring huge amounts of courage, did not require huge amounts of technical know-how. Anyone could gather their homework, sit at a lunch counter, and wait to be ignored, arrested, or beaten up. You could watch the news or hear about it from your cousin and very quickly organize a similar group in your town.

-

Make the Big Ask. This was not the first act of the Civil Rights Movement, so almost everyone knew the risks they were taking; jails and injury were ahead. But the stakes were also clear. The sit-in movement had provoked the white supremacist infrastructure in a way the lawsuits had not. We all have it deep inside us to understand that, without risk, nothing substantial can be gained. The ask, the stakes, and the possibility of success must be clear to compel large numbers of people to action.

-

Finally, movement support infrastructure is vital. This one is the trickiest and is a question of calibration and nuance. As mentioned above, each city or town developed its own infrastructure to undergird the sit-in movement, but there were some common components, and the role of the Black Church in creating some level of financial independence cannot be overestimated. The pieces of infrastructure outlined below were especially important.

- Organizing and outreach: The sit-in movement moved quickly from Black colleges to high schools. In High Point, North Carolina, for example, Mary Lou Andrews, a 15-year-old student at the all-black William Penn High School, began meeting with friends to stage a sit-in. She approached local Reverend Benjamin Elton Cox and a retired teacher, Miriam Fountain, who agreed to train the students in nonviolent resistance at his church.

-

Meeting, copying, money: The Black Church as an autonomous space was critical in the success of many parts of the Civil Rights Movement. It served as a place for food and, most importantly, a meeting and organizing spot. Some even had mimeograph machines that made it possible to print materials at scale. In some cases, Black colleges were safe places to congregate, but, in others, having an independent entity was key.

-

Allies and legal: I am looping allies and legal together because they both work to protect the protest. If there are no lawyers to check on the health and safety of those who are arrested or beaten, then government and vigilante groups can act with impunity. Second, without an ecosystem of allies, the protests lack legitimacy.

-

Training: As mentioned earlier, Nashville had an incredibly effective training infrastructure led by the brilliant Rev. Lawson. Other places also had seasoned veterans who could help prepare students for some of what they might encounter as they took action, as was the case in High Point.

By taking bold action, recruiting an increasing number of participants, maintaining nonviolent discipline, and engaging in confrontational protest for as long as it took, the Greensboro 4 launched a movement that spread like wildfire and created a ruptural moment that changed the course of history. Sometimes, just taking the first step can light the match and create rupture.

References

Charles Payne, I’ve Got The Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle

Erin Pineda, Seeing Like an Activist: Civil Disobedience and the Civil Rights Movement

Michael Walzer, “The Young: A Cup of Coffee and A Seat,” Dissent, Spring 1960

Steve York, A Force More Powerful (film with study guide by International Center for Nonviolent Conflict)

Personal interview with Mary King, Professor at the University for Peace

Personal interview with Sekou Franklin, Professor at Middle Tennessee State University

Notes from workshops with Dr. James Lawson at the James Lawson Institute, 2013