Californians for Justice (CFJ) was founded in 1996 to fight an onslaught of state legislation targeting working-class people, immigrants, and communities of color. But money for our electoral programs was hard to come by, and our endless defensive strategy made the work unsustainable for our membership base and organizers. We began to reflect on how to most effectively build and actualize power for young people, their families, and their communities, and, three years after our founding, we made an intentional shift to organize young people of color around racial justice in public schools. We won a number of key education campaigns, but these policies too often failed to translate into lasting material changes in the classroom because of the attitudes, biases, and practices of district and school leaders. We needed to shift from demanding policy change to commanding actual power — from calling for increased resources and an end to racist policies to changing the attitudes of adults in schools and empowering young people as decision-makers.

Beyond Policy Wins

In the early 2000s, statewide education organizing was dominated by the school-to-prison pipeline. But it quickly became clear to our base that the California High School Exit Exam (CAHSEE) was an immediate barrier to Black, brown, and immigrant students. We built a statewide alliance of various stakeholders — including youth organizations like InnerCity Struggle (ICS) and Community Coalition (COCO) as well as advocacy and legal organizations like Public Advocates (PA) — for the “Stop the Exit Scam” campaign. At the time, 81 percent of recent immigrants, 74 percent of Black students, and 70 percent of Latino students had failed at least one part of the exit exam, meaning that hundreds of thousands of students were ineligible to graduate from high school. We knew that overturning the exit exam would not get to the root of California’s unjust education system, but the campaign would allow students of color and their families to highlight the injustices they faced and demand real change. Within months, hundreds of Black, brown, and immigrant students flooded the state Capitol, demanding that lawmakers not “throw our futures away.”

The campaign only succeeded in winning a two-year delay, but it cemented a powerful coalition of education justice organizations, developed an infrastructure for young people of color to shape education policy, and articulated a vision for education justice — setting in motion two decades of unified campaigns around a shared vision for racial justice in our schools. In the coming years, we racked up a number of policy wins. Our “So Fresh, So Clean” campaign won one billion dollars to update public school textbooks and fix run-down facilities. We established an ethnic studies program in the Central Valley, pioneered the first farm-to-school cafeteria community gardens in Long Beach, and made A-G university entrance courses mandatory for all students in East Side San Jose, to name just a few of our victories.

These policy wins were critical in calling attention to the racial inequities within California’s education system and putting the vision of students of color at the forefront of education organizing. Our issue-based campaigns also built a pipeline of dozens of youth organizers. However, our collective vision to change the material conditions in our classrooms eluded us. Too often, the policies we passed were watered down by district leaders, principals, and teachers, whose approach toward teaching and learning was steeped in white supremacy and anti-Blackness. The policies changed, but practices within our schools and classrooms did not. Even when we won the Student Equity Funding Formula — the first equity funding formula for public education — students were left out of the decision-making process for how to allocate funds. This wasn’t just a problem of individual attitudes; we saw this failure of implementation and resistance to including student voices and leadership system-wide.

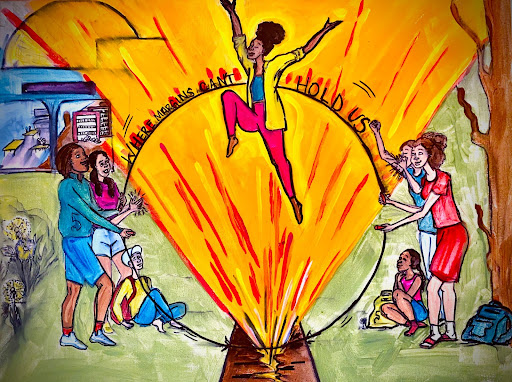

We asked ourselves: what will it take to radically transform public education? To actualize our vision, we had to build real governing power for young people within our school system. We needed to start with a powerful vision for racially just public schools that was rooted in the experiences and imaginations of Black, brown, immigrant and low-income youth — a vision that could transform adults in the education system and bring them to our side.

A Shift Toward Transformative Organizing

After speaking with over 2,000 young people and adults within our public schools, what emerged as the issue that could change a young person’s life and transform schools was relationships — young people’s relationships with the adults at schools, their relationships with each other and themselves, and their relationships with a powerful institution like education. But what would it really take to transform relationships? One, it would require a strategy to shift the culture of the adults in our schools. Two, it would require us as organizers to practice embodying racial justice. And three, it would require an inside strategy to transform relationships and build critical mass within our schools.

We doubled down on a narrative and cultural strategy to address the racist perceptions of teachers and administrators — what we called the “belief gap.” That belief gap mirrored itself throughout the school system, from the ways students were tracked into different programs to the ways educators disciplined and taught them. We experimented with new practices to move adults to share power with students of color. One tactic that proved especially effective was having students of color lead in education spaces to show adults that they were experts on the solutions needed to change the education system. We advocated for students to facilitate and participate in district learning days and school site retreats. We held student-led professional development on topics like racial bias and white supremacy culture for district and site staff, opening the door for administrators to partner with students to shift school climate and culture. We also advocated for students of color to serve on hiring committees, instructional leadership teams, and school culture and climate committees. Over time, we began to see adults in the education system value students of color as partners in creating more racially just schools.

While we moved to shift the culture in our schools, we also called on ourselves to embody and practice racial justice as organizers and leaders. We explored how white supremacy culture shows up in our own organizing. For us, it showed up as perfectionism, a constant sense of urgency, and either/or thinking — the same practices that show up in our schools and communities. To address this, we made an intentional effort to model leadership and school site transformation planning with democratic and equitable decision-making that centered the perspectives of marginalized students. We practiced shared governance and emphasized purpose, spaciousness, and joy. These shifts led to a deeper sense of connectedness and established a strong baseline for shared purpose and accountability among the young people and adults in our schools.

We also developed an inside strategy to complement our outside strategy. Too often, our policy wins were implemented poorly or not at all. The excuses given — there’s not enough resources or staffing, the problem is class, not race, not everyone is meant to succeed, or students just don’t care — are ones education justice organizers hear all too often from adults in schools. To counter these attitudes, we organized adult champions. When we launched our Relationship-Centered Schools campaign, we conducted one-on-ones with education leaders at the school, district, and state levels to ask them to be our messengers in public meetings, the media, and district and school site plans. Within a few years, relationship-centered schools became an important issue within California’s education landscape. The concept even showed up in the strategic plan for Hayward Unified School District — a district we hadn’t organized.

Challenges of Transformative Organizing

The process of transforming schools from the inside is long, arduous, and, at times, fatiguing for our members and organizers. Our Relationship-Centered Schools campaign is a five-year campaign, much longer than the typical policy-focused campaign. The work is emotionally laborious, especially for those of us who are impacted by multiple systems and isms. It can be exhausting to think about how to address the practices and root causes of perfectionism, power hoarding, and either/or thinking within our schools.

We try to offset the impact of this work by building in joy, spaciousness, and a sense of purpose. This has translated into training on emotional labor for staff, restoration weeks (paid time off), quiet Fridays, and emergent strategy and embodiment practices like Forward Stance. We lead short statewide policy campaigns backed by our four regions (Long Beach, Fresno, San Jose, and Oakland) to make transformation more possible locally. We’ve also become much more intentional in our hiring practices. We are candid with prospective staff about what our current organizational culture is really like to make sure our organizers are committed to taking on this approach with us.

Another challenge with our inside approach is that it can make our organizing appear centrist to organizations that lead with an outside strategy. It’s an ongoing tension within our work. We spend a lot of time meeting school staff where they are and emphasizing the everyday practices necessary to dismantle white supremacy culture and build racial justice within our schools. We build power with local and statewide teacher’s unions because we know that educators are integral to achieving racial justice and transforming beliefs and practices in schools. At the same time, we know that not every person can be transformed — those who perpetuate white supremacy through the tracking and policing of our students have no place in our schools and communities.

Conclusion

This work has compelled us to push hard and fast when the moment emerges and to go slow when the school community calls on us to — to hold both the short and long view toward the total transformation of the education system. Martin Luther King, Jr., said that the arc toward justice is long. It’s a quote we often refer to when the prospects of justice are far, and progress is hard. The question CFJ organizers and leaders continuously ask ourselves is, what about now? How do we reimagine and rebuild schools rooted in joy, schools that give students space to be, cultivate a deep love for learning and humanity, and instill in students the foresight and skills to take on the social and environmental crises of the 21st century?

While we work to change the material conditions for Black and brown youth within public education, we hold the short and long view — the work to transform our material conditions right now and the work to transform future generations. Fighting for generational transformation requires our organizing to be vast and dynamic. We must find ways to take over the whole system, not just change policies. Lasting, systemic transformation will never happen unless we change the people, the culture, and the power young people of color have over their lives. Doing that work takes a disciplined commitment to ongoing power analysis, embodying racial justice, building relationships that transform hearts and minds, and developing a strong pipeline of youth leaders. We cannot stop until every inch of our institutions embodies our vision.