Last year, at the pinnacle of a campaign for climate justice policy in New York, I was faced with a choice familiar to many over-extended organizers: should I put all my energy toward an immediate policy victory or should I focus on long-term power building by bringing new individuals and organizations into our coalition? I’m the lead coalition organizer at NY Renews, a climate justice coalition of over 300 organizations, where I am tasked with both running campaigns and deepening our coalition. Our coalition had just completed a statewide week of action, with 16 rallies, 44 lobby visits, and a large capstone event with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, all of which attracted people and organizations far beyond our normal reach. Now was the perfect time to bring new organizations into our coalition and grow our base. But our key coalition members and staff were worn out, and we had just four weeks until the next major mobilization on our campaign calendar.

In preparation for the legislative session, I had sought out training on absorption — the practice of bringing new individuals into an organization during moments of heightened activity — and created a plan for exactly this moment in the campaign. The absorption plan included a series of mass calls, one-on-ones with all the new people who had led rallies, and digital actions geared toward the hundreds of new people on our email list. But in the end, the campaign calendar loomed. While we had a mass call, I made the choice to prioritize our upcoming actions rather than implement all of the absorption measures. Without these measures, we lost an opportunity to build longer lasting and deeper power.

After the campaign ended, I reoriented my organizing approach to focus on deeper power-building alongside campaigning. As a coalition organizer, this has meant developing deeper relationships with coalition members, bringing new coalition members into our committees and day-to-day organizing, and developing members’ skills, knowledge, and buy-in.

Many organizers have been calling for a renewed focus on long-term power building over short-term policy wins and the adoption of more rigorous organizing practices. In my work, this means doing both the prep and follow up work to promote leadership development and bring in new individuals instead of solely pushing campaign goals. In practice, it means focusing on the details that lead to building up, not drawing down, power over time.

Rigorous organizing takes a lot of time — time that organizers like myself rarely have. To actually organize rigorously, we need to take on less. Luckily, doing less, like any skill in organizing, is something that one can practice and master. Here are a few key practices that I’ve adopted to shift my organizing approach toward deeper power building.

Practice #1: Using the strategic “no”

The strategic “no” is the most fundamental skill for shifting to a power-building approach rather than a campaign-oriented approach. While it sounds simple, the strategic “no” is anything but easy. It requires reframing your guidelines for taking on work, trusting in your long-term vision, and cultivating courage.

When considering an ask, I have had to learn to make the shift from, “Is this something that will help my campaign/action/etc?” to, “Is this something that helps my campaign more than doing what I’ve already committed to in a rigorous manner?” The latter highlights the cost of saying yes to something new. While this shift may seem small, weighing the opportunity cost in every decision has been transformative.

Recently, a trusted coalition member reached out to me about co-creating a rally in an area of New York State in which our coalition hasn’t historically had a strong presence. While I was tempted to expand our geographic reach, I told them that I needed to honor my existing commitments by giving them my full capacity. By saying no to the rally, I was able to focus my time on building out our faith engagement table, which resulted in a dozen new faith groups joining the coalition and engaging in a new bi-weekly committee.

Saying no requires that I trust my own vision. Without a clear vision of where our coalition wants to go and a commitment to the path to get there, I am unable to discern between uses of my time that bring our coalition closer to our goals from those that are a distraction. For example, our coalition is asked almost every month to join partners in advocating for other pieces of climate or environmental justice legislation. When I say no, we lose the opportunity to help pass meaningful legislation but are able to stay laser focused on the legislation that we drafted together as a coalition. This doesn’t mean that our coalition can’t ever reconsider our long-term strategy, but it does mean that every small decision doesn’t become a reevaluation of that vision.

The strategic “no” takes courage. It is hard to say no to someone you have a relationship with or who has more power than you. One strategy I’ve employed when I feel unable to say no in the moment is to say that I need to check in with folks before I give an answer — which is often the case anyways. Then, I take a bit of time to figure out how to craft a strategic “no.”

Practice #2: Frontloading campaign strategy with power building in mind

Our campaign calendar used to be filled with mobilization after mobilization. To disrupt this pattern, I now make a practice of carving out time before and after mobilizations to focus on long-term power building, first through creating leaderful teams and then through absorption.

I’ve had to let go of evaluating the strength of our campaign based on the amount of campaign activity and instead focus on whether this activity is getting us closer to winning and building long-term power. This freedom allows us to run a campaign that can actually grow our base and develop new leaders instead of drawing down on the power of already-engaged coalition members. As a result, our legislative campaign can actually be a conduit for building power instead of just using it.

I’ve also had to overcome my own doubt. When I first looked at our campaign calendar, I was worried: what if I don’t have enough planned for the legislative session? But I’ve learned that I can always add in actions later; stopping events that are already in motion or saying no to something that we’ve already committed to is much more challenging.

Now, our coalition’s campaign calendar is less jam-packed and has time built in before and after mobilizations to allow for leadership development among our existing members and absorption of new members. With the extra time, I’ve been able to create a faith engagement table and a sustainable business table to organize underrepresented sectors of our coalition. Additionally, I’ve worked with other staff to create and implement a regrants fund for smaller coalition members to give them the capacity to build power in their own communities.

Practice #3: Letting go of control

Letting go of control is critical for leadership development and more rigorous organizing. Letting go has freed up my time to work on non-campaign oriented projects while simultaneously opening up the space to let coalition members step into leadership. This can be done in macro ways, by shifting to a more distributed organizing model, and in micro ways, by handing off responsibilities to leaders and volunteers while moving staff into support roles.

As a coalition organizer, I often coordinate teams of coalition members to help plan an action. In the past, I was part of every subteam, helping to craft the run of show or supporting the creation of outreach materials. Now, my role is much more about supporting the leaders of the subteam through one-on-ones and setting a standard of rigor by creating checklists of “must-dos” for each action and ensuring that there is enough attention to items such as follow up.

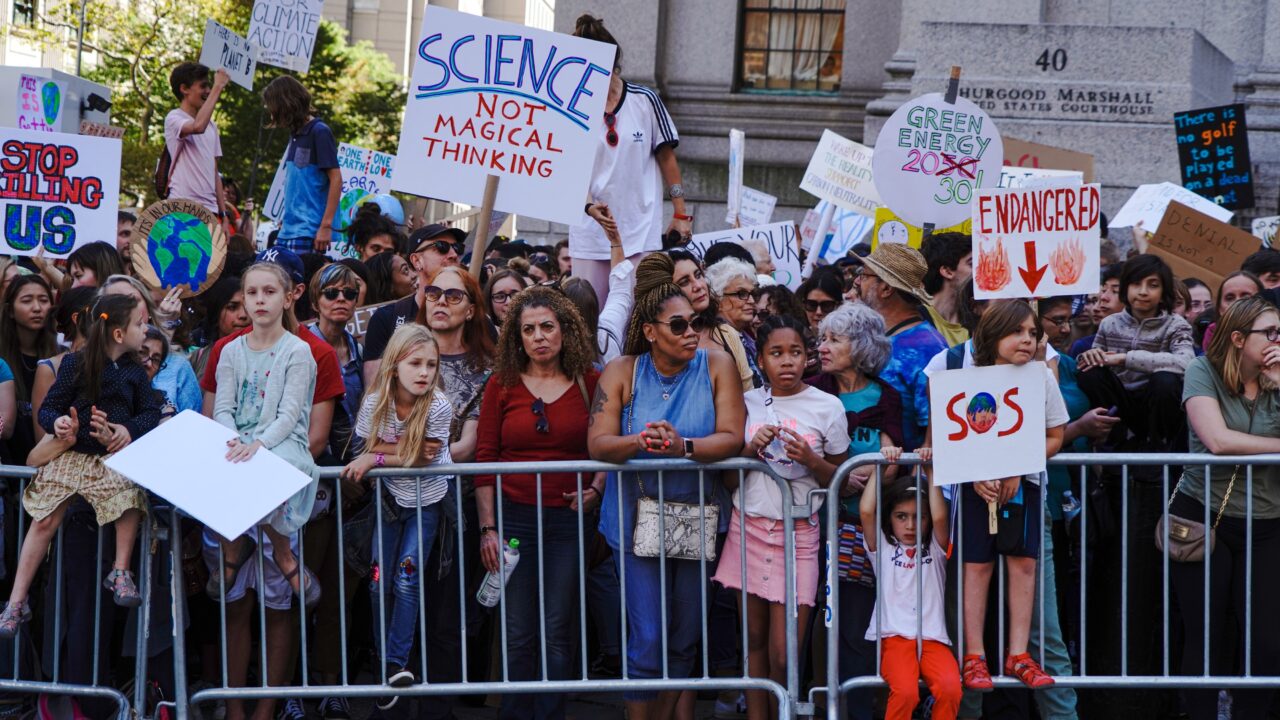

Recently, our coalition planned three large marches ahead of the release of New York State Governor Kathy Hochul’s 2022 budget proposal. I did outreach to key coalition members to see if they could create and lead a planning team for each march. We developed a timeline and list of activities for each planning team to focus on during the eight weeks leading up to the marches. Coalition staff met with team leaders every week — checking in on their progress, supporting them with agenda creation, and providing logistical support. As staff, we held meetings to assess the progress of each march and coordinate messaging across the marches. While each march had a different action plan, they all had the same target, messaging, and standard of organizing. Most importantly, delegating responsibility built the leadership and trust of the coalition member staff and volunteers planning the actions.

I’ve had to accept the reality that things will go differently than they would if coalition staff were in charge — some things might even go wrong. But delegating responsibility gives coalition member staff and volunteers the chance to make mistakes, and with it, the chance to grow. This makes our coalition stronger in the long run.

Conclusion

While the strategic “no,” frontloading campaign strategy, and letting go of control have all helped me create more space for rigorous organizing, the deeper shift is a more existential one. Utilizing each of these skills requires letting go of the idea that success in organizing is determined by the amount that we do. Instead, it opens up the possibility that success is measured by the power we build and the practices and culture we create in the process.

None of this is easy, especially given that funders and those more removed from on-the-ground organizing are often unable to see the value of long-term power building. But without these practices, rigorous organizing and long-term power building will remain just-out-of-reach goals instead of ongoing processes. With these skills and practices, organizers can turn campaigns into conduits for long-term power building.