As a union organizer with 38-plus years of experience, I was filled with awe to watch Chris Smalls, Amazon Labor Union (ALU), and the United Congress of Essential Workers (UCEW) turn traditional labor organizing orthodoxies on their head. I must admit that I didn’t think they would succeed — largely because of just how broken labor laws are and how hard employers and corporations will fight to stop employees from unionizing. But their creative use of direct action tactics inside and outside the workplace, their social media and communications strategy, and their relentless work at bus stops and inside the warehouse kept their drive alive against all odds — and helped pave the way to victory.

At Starbucks, a worker-leader movement has won more than 200 elections at stores across the country with the support of Workers United (SEIU). While the minutiae of the Starbucks organizing are not fully known, there’s no doubt that their model is also groundbreaking — the use of social media, the homegrown leadership, the direct action tactics at targeted stores.

These drives were anchored and driven by workers organizing with their coworkers. They give ample support to the idea that a union is more than a legal outcome; it is a vehicle for workers to build power and act like a union before, during, and after they’ve filed for a union election. It’s not that these campaigns are ignorant of the challenges and limitations of current labor law. On the contrary, they’re teaching us the importance of deeply understanding the mechanisms, rules, and remedies available through the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) and other US labor laws like the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) while supporting workers in the strategic utilization of walkouts, picket lines, and other direct actions permissible under the law. In doing so, they are demonstrating that not every decision in an organizing drive needs to be made by paid staff or local union leadership. Rather, strategies can and should be developed at organizing committee meetings so that workers can develop plans that work for them and the needs of the drive. By trusting workers and empowering them to act like a union, ALU and SBU are building power, moving their campaigns along, and creating a path to collective bargaining and better working conditions despite the hostile legal terrain and vicious employer-led anti-union campaigns.

Lessons from Care Worker Organizing

The current wave of worker-led union organizing brings to mind lessons I learned as a younger organizer supporting fast-food workers in 1980’s Detroit, as well as my experiences organizing over the next four decades with homecare and childcare workers in the public and private sector. Both of these efforts cemented the importance of centering workers in union organizing and made clear that our work as organizers is to help them as they learn what it means to build power by acting like a union.

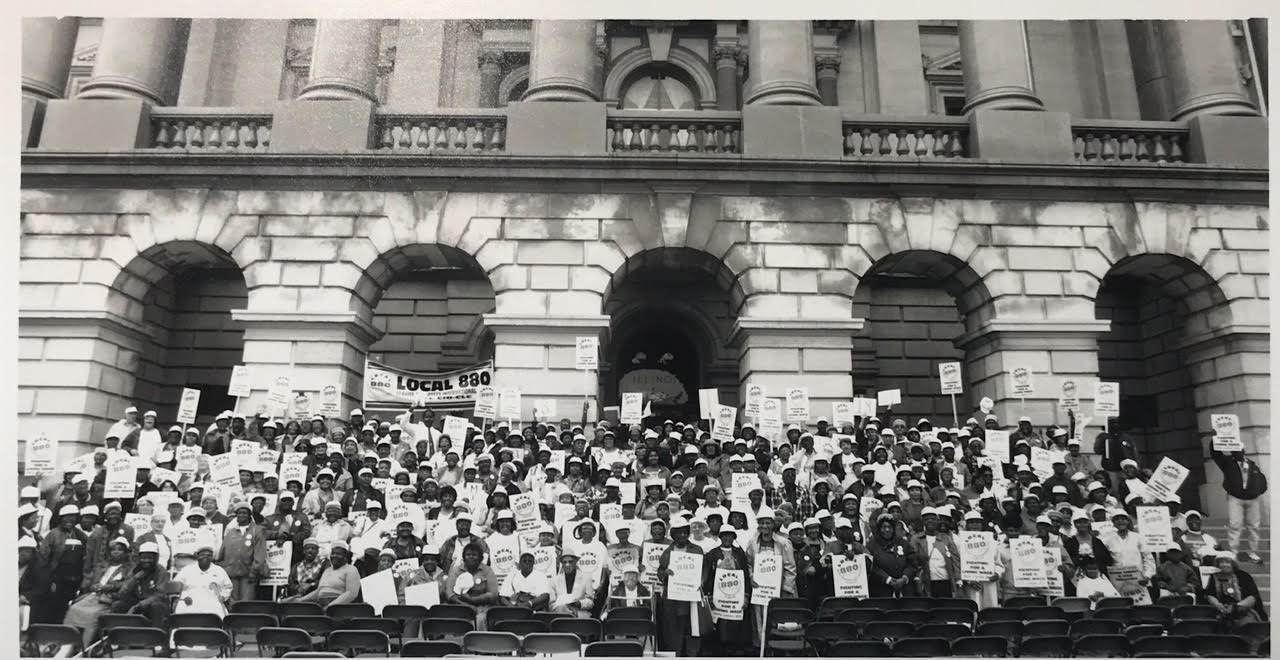

Some examples: In December 1983, the 200 workers at McMaid, a homecare agency in Chicago, won their first union election organizing with the fledgling, independent union, United Labor Unions (ULU) Local 880 (later SEIU 880), which I helped found with ACORN (Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now) in Chicago. Led by homecare workers like Irma Sherman [bottom left in the photo below] and Doris Gould, we organized against a tough anti-union campaign and won the vote. But the employer spent the next two years delaying at the Labor Board and at the bargaining table. We had a decision to make: allow the employer to stall and wait for the results of their legal appeals while our leaders and members were fired and our majority whittled away — or take action on and off the job to keep our members involved, engage the employer in a direct action campaign, and publicize management’s anti-union behavior. We decided to take action. We took on the company not only at the Labor Board but also with ACORN, our community allies, and the public at large. We attacked their state contract, their stalling at the Labor Board, their low wages and benefits, and their racist and sexist management. We even visited the employer at his Barrington Hills horse farm estate northwest of Chicago, demanding that he come back to the table and settle a fair contract — and we flyered his neighbors, asking that they call him at his home number and tell him to negotiate in good faith. He eventually did. We found out that client consumers could transfer to other agencies if they were unhappy with their care, and we organized the workers and consumers together to demand the company settle a contract. They threatened to move en masse to another agency, effectively striking the company but keeping their jobs and consumers. And we worked with our community allies through ACORN on community issues like utility shutoffs, affordable housing, and living wages. The result: at the last minute, the employer settled, and we won the first private sector homecare contract in Chicago and Illinois history. In the process, we developed a model of acting like a union that helped us organize the majority of the private companies and public homecare workers in Chicago and eventually statewide. After McMaid, we won Staff Builders services, led by Essie Stinson, Lula Bronson, and Mary Williamson, and later, DORS, led by Helen Miller and many others. Over the next 20 years, our aggressive model eventually helped bring thousands of new members into ULU (later SEIU Local 880, which is today known as SEIU Healthcare Illinois, Indiana, Missouri, and Kansas, or HCIIMK). Not only that, but we also won key victories with our community allies on utility shutoffs, affordable housing, and living wage campaigns.

Top: McMaid leader and now president of SEIU Local 880, Irma Sherman (left) and Chicago ACORN leader June Torres (right), present Mayor Washington with endorsement letters and over 5000 new voter registration forms of newly voters registered by SEIU880 and ACORN. Bottom: DORS leader and 880 Treasurer, Helen Miller (2nd left), McMaid worker and 880 President Irma Sherman (left), and Staffbuilders worker and 880 Secretary, Essie Stinson (right), lead the applause for Mayor Washington as he enters the rally.

As homecare workers continued winning lopsided union election victories, some of the private-sector homecare employers in Chicago came up with a new and novel theory to stop the union wave. They claimed homecare workers weren’t really their employees but rather employees of both the state of Illinois and the private-sector homecare agencies, in effect meaning they had no rights to organize under the federal or state Labor Relations Acts. Ditto for the public sector workers – they were told that they were “independent contractors” and were really employees of the client or, at best, employees of the state and the client and thus had no rights to organize a union. Our job as organizers was to support the development of strategies and campaigns through which the workers could fight on. Helping workers understand their power and what it meant to “act like a union” is a big part of how we were able to survive and thrive — eventually growing from seven members at McMaid into a recognized union with over 70,000 homecare and childcare providers.

Long-Term Organizing and Building Paths to Power

Organizing today is hard, expensive, and time-intensive. Most unions and many organizer training programs rely on the deadeningly slow mechanisms available through federal or state labor laws — all of which have been neutered over the decades by right-wing Democrats as well as Republicans. Unions spend weeks training new organizers to make house calls and assess individual workers. This isn’t wrong. It is critical to know the numbers, to be clear on the level of support and challenges in the workplace and to understand where workers across a facility are as they head into a union election. But this methodological organizing is not the sole avenue to building organization and power at work. Conversely, other unions center their strategy on leverage with capital-intensive “corporate campaigns.” For some workers and industries, these strategies are necessary and do end in huge victories, but many of these campaigns take years and millions of dollars in resources. Even when they succeed, they are often won without much active worker participation. When the campaigns fail, this does double damage to efforts to build worker power.

What the labor movement needs will not be found in the hundreds of power points across union board rooms but in workers organizing together to win at the grassroots level. To beat the country’s biggest employers, we need to organize with workers who want to build power and are ready to act like a union for the long haul. Today’s new wave of worker-driven organizing is a reminder that workers are willing to go to extraordinary levels to build their union. We have to be prepared to follow and support workers along the way, and ensure that we’re not missing the opportunity to teach them what it means to be a union. This means organizers must remember to center workers and collective action in a number of ways, including:

-

Building workplace organization and taking action in the workplace: Whether it’s taking strategic action at a company orientation or training, organizing delegations into corporate offices or rooms of power, or having worker leaders take ownership of mapping and organizing conversations, we have to re-center worker participation in organizing. At all of our early homecare organizing drives, the committee members planned the recognition actions on the boss. We roleplayed various responses to what the boss or supervisors might say or do and then debriefed to decide on next steps. That went a long way to allay fears of firing, closure, or other threats.

-

Ensuring workers exercise collective power politically: Organizers can support but must not replace workers in planning a march at the state capitol or a sit-in at the office of an elected official. I’ll go further and say that organizers and unions can’t be afraid to ruffle feathers — particularly political ones — as we support workers in planning collective actions to improve working conditions on the way to union recognition and a contract. We can and should use the political process strategically to achieve goals like raising wages and improving standards.

-

Organizing money, resources, and support together: We should never be afraid to ask for help, especially when we are trying to pool our resources and move our campaigns. Seeing Amazon workers raise money through GoFundme reminded me of the importance of asking for help — and realizing how much support we had. Back then, we asked members to pay dues in cash, we sold chicken dinners, we held potlucks as fundraisers, we canvassed door-to-door to ask people for financial support, we sold raffle tickets — we had workers doing everything they could to raise the money to build the union.

-

Developing a larger strategic framework: Workers understand that the fight doesn’t stop in their workplace. Care workers expanded their organizing to other homecare agencies and, later, childcare agencies in order to bring more workers into the fight for higher wages and standards. They understood that they needed a larger critical mass to force the companies (and the state) to change their ways. Later, they expanded to organize other homecare and childcare agencies across the state and around the country.

-

Fighting until you “win” and then continuing to build: Just because labor laws are broken does not mean workers should not engage in the policy and politics. On the contrary, these are realms in which workers can engage in “guerrilla” fights against their anti-union employers and build the organization that can win the political and legal changes needed to access collective bargaining. Acting like a union can look like workers demanding that the state take action when an employer violates the law or a group of workers filing a claim and working through the courts and government bodies to win monetary remedies for wage theft. Winning hundreds of thousands of dollars in backpay makes clear to the workers why they’re organizing and what it means to act like a union.

Workers, Organizers, and Unions Need to Fight Like Hell and Act Like A Union

To the naysayers, particularly those in labor, I would say that our local union of care workers went from being the smallest local in the entire Midwest to the largest. And SEIU, once one of the smallest unions in the US, is now the second largest union in the country, with over 750,000 homecare and childcare workers in its ranks. That means that over one-third of the two million workers SEIU represents are workers who many said would never win, were not really workers, or had no rights to a union.

We didn’t organize this many workers by waiting for the correct historical moment or for the right politician to be elected or for labor law to change. We did it by taking strategic action in all those spheres. You don’t go from zero workers to 100,000 workers overnight. You build those numbers incrementally by signing up members, running direct action campaigns, and acting like a union.

The labor movement needs to do what workers are doing at this moment: take action and look to make deep change. We need to relearn that there is power in a union — and that workers themselves moving in collective direct action have power. In the case of McMaid, seven workers who met in a church basement in 1983 were bold enough to make a commitment to organize a union of homecare workers, regardless of whether it was legal. Irma Sherman, Doris Gould, Mary Williamson, Helen Miller, Essie Stinson, Lula Bronson, and many, many others set off a movement of homecare and childcare workers that are now the foundation for one of the largest increases in new members — primarily women and women of color — into the labor movement in the past 40 years, changing not only the industry but the face of the labor movement.

It has been especially gratifying to read that many workers at Amazon and Starbucks have relatives who were homecare or other essential union workers — and how important that union connection has been. As this new generation of workers moves forward in their fight for union recognition, and as employers find new legal obstacles to frustrate and delay them, the most important goal of the organized labor movement should be standing in solidarity and taking action to support them.