This article is part of Countervailing Power, a joint series by The American Prospect and The Forge that explores the ways organizers can use public policy to build mass membership organizations to countervail oligarchic power. The series was developed in collaboration with the Working Families Party, the Action Lab, and Social and Economic Justice Leaders.

At the end of January, the White House released a set of actions designed to improve fairness in rental housing. The announcement was the result of a pressure campaign launched by housing activists and tenant unions across the country. Specifically, the Homes Guarantee Campaign, an arm of the community organization People’s Action, met repeatedly with White House officials to demand executive action on rent regulation.

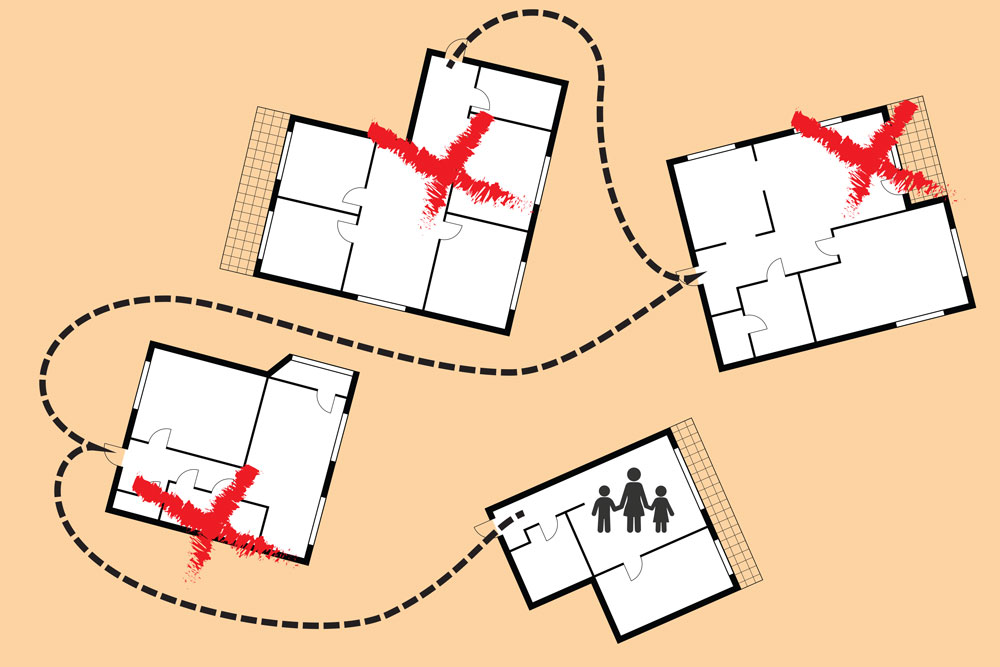

It was another step in a tenant organizing wave that has seen major victories across the country. In Kansas City, organizers won the right to be provided an attorney in all eviction cases, building off of similar programs in New York City and elsewhere. In Los Angeles, tenants won “just cause” eviction protections just weeks after successfully passing a ballot measure that builds affordable housing and makes rental assistance funding permanent. And at an apartment-by-apartment level, tenant unions are winning residents the right to buy their properties, and preventing unlawful evictions.

By building power, the Homes Guarantee Campaign’s organizers wanted to move their ambitions to the federal level, and win advances for all renters. While they did not achieve the broad and aggressive executive action they were hoping for, the White House announcement reflects the work of the tenant-led campaign, and contains various firsts for the administration. The White House has created information collection directives by enforcement agencies on potentially unfair or deceptive rental practices, a study from the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) on whether to tie future rental housing investments to renter protections and limitations on rent increases, a new rule requiring 30 days’ notice before lease terminations due to nonpayment of rent in public housing, and a review of potentially anti-competitive information-sharing by landlords.

In addition, the White House announcement encouraged a “whole-of-government approach” to making rental housing work better. It is part of the administration’s Renter’s Bill of Rights, a blueprint of which was released the same day.

These actions fall far short of the executive action that could have been taken to alleviate pressure on renters across the country. In fact, lobbyists for the National Apartment Association bragged that their advocacy blocked the executive order.

“The reality is [the] announcement really did not do anything materially to change conditions for tenants who are struggling to pay the rent,” Tara Raghuveer, campaign director of the Homes Guarantee Campaign and director of KC Tenants, said.

The Biden administration could clearly do more. But the Homes Guarantee Campaign managed to bring together average Americans who have one thing in common—rent—and organize them into a tenant-led force that was heard by the White House and Congress. The campaign may not have gotten exactly what tenants need yet, but they intend to be heard again, increasing power as they agitate for more change. Not only is the coalition building the movement for policy victory; the organizers are building the coalition with the policy.

ORGANIZERS WITH THE HOMES GUARANTEE CAMPAIGN have been pushing the Biden administration to address the affordable-housing crisis. The housing crisis may have been exacerbated by the pandemic, but the need for protections has been urgent for decades, especially after the 2008 housing crash.

People with the Homes Guarantee Campaign have been organizing since 2017, connecting to local organizations such as the Jane Addams Senior Caucus in Chicago, to build a coalition of renters. Energy had begun to rise for reforms such as Medicare for All and the Green New Deal, and organizers with the Homes Guarantee Campaign recognized the lack of a comprehensive agenda for housing. By 2018, organizers would hold a congressional briefing to further explore how to create a “north star” for housing policy.

A year later, the campaign released its Briefing Book, outlining the state of tenants in America, the need for actionable change, and how housing organizers can channel their energy into it. As Raghuveer explained, the book immediately made waves in the progressive sphere, influencing Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren’s housing plans in their presidential campaigns. The document advocates for a Tenant’s Bill of Rights, which would eventually become part of Joe Biden’s housing plan as well. That was in some ways the goal, to shift mainstream Democratic policy at a time of leverage before the presidential election, and to build a comprehensive housing policy along the lines of the frameworks for Medicare for All and the Green New Deal.

So when the pandemic hit, the Homes Guarantee Campaign was already poised to tackle the issue. Federal officials quickly put in a moratorium on evictions. But with 30 to 40 million people at risk of eviction once the moratorium ended, People’s Action recognized that action would be urgently needed.

The campaign’s solution was H.R. 6515, the Rent and Mortgage Cancellation Act, which would have canceled rents at the federal level amid the pandemic. Despite campaigning intensively, the group never got anywhere and was forced to reassess what power the campaign could wield.

“It never before felt as urgent and critical that we figure out how to build that power as it did that summer because so many of our people were in such immense pain,” Raghuveer said.

This is an important moment for any movement: when the need for change, as well as the resistance, is so great that there is no other option but to pivot and choose another front to fight on. Congress may have been a dead end, so the campaign quickly zeroed in on the White House.

Weighing the needs of tenants and centering them in the process is the core of the Homes Guarantee Campaign. This thought process is what led to the campaign bringing tenants directly to Washington to engage with political leaders. The first time was in September 2021, with just 11 people. The tenants got commitments from the White House for further engagement, so the Homes Guarantee Campaign went back again.

And again, and again. The campaign has now had meetings with Housing and Urban Development Secretary Marcia Fudge, Federal Housing Finance Agency Director Sandra Thompson, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Director Rohit Chopra, and many others. The campaign was tapping into the power of storytelling, explaining how the rental crisis had affected them personally and often detrimentally.

Organizers were wielding the lived experiences of people to demand change. By doing so, the Homes Guarantee Campaign gave voice to the broader tenant movement, eventually engaging over a million tenants in the ongoing process of writing a National Tenant’s Bill of Rights.

“Tenants are the experts of their own experience,” Raghuveer said.

THE GOAL FOR CHANGE, and the purpose of the Homes Guarantee Campaign, is to prevent uncertain housing situations for people like Mary Osborne of Dover, New Hampshire. Osborne is a member of a tenant union, and a single mother who has been housing-insecure at various points in her life. When she found herself in a domestically violent situation, she knew she had to leave.

“It took a very long time for me to leave because I knew that my only options as a disabled single mom would be to go into a homeless shelter,” Osborne said. “And I wasn’t for certain if I could do that, especially having a son who is autistic.”

Osborne’s other option was to apply for an emergency housing voucher through Section 8. In 2001, Osborne had also applied for an emergency housing voucher, and received one within a month.

Twenty years later, the process was much harder. Osborne looked for several months before she was able to secure housing through almost a stroke of luck, submitting an application just after it was posted and speaking with an empathetic property manager. The problem, in Osborne’s view, was that the value of vouchers was not keeping up with rising rents.

“The rents were skyrocketing, exponentially,” Osborne said. Indeed, between February 2021 and February 2022, rental prices increased over 17 percent, while wages have only just begun to go up. In addition, many landlords are either not accepting Section 8 or raising the rent just over the value of the voucher.

This experience pushed Osborne to start working with housing justice organizers, eventually leading her to a statewide tenant union in New Hampshire. The union has been working to educate people about their tenancy rights in the state and start local chapters, as well as working with the Homes Guarantee Campaign.

“There is this misconception that if you are a human being that requires help, then there is something wrong with you, that you are not worthy,” Osborne said. “It’s been my goal to let them see that I’m a valued community member.”

AFTER MULTIPLE MEETINGS, the campaign promised to bring more than 100 tenant-delegates to demand Biden sign an executive order guaranteeing rental protections, which they did two days after the campaign released a prewritten executive order that lays out a clear policy framework for the Biden administration to follow.

“It is the policy of this Administration that everyone should have access to safe, accessible, and truly affordable housing,” the mock order reads. To achieve this, the executive action would create, among other things, a Federal Interagency Council on Tenants’ Rights; investigations into consumer reporting companies and their tenant reporting agencies that the order alleges are a violation of the Fair Housing Act; and a mandate that the Department of Justice enforce fair housing. The mock order acknowledges the racial disparities inherent in housing as well.

Osborne joined these tenants in Washington, D.C., to present President Biden with their order. On the trip, they met at the White House with the Domestic Policy Council and the National Economic Council. A day later, they met with Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and representatives including Jamaal Bowman (D-NY) and Cori Bush (D-MO).

Davita Gatewood, a tenant union member from Lexington, Kentucky, was another member of the tenant delegation. Gatewood is also a voucher holder, as well as a single mother to six children—her oldest is 23. She said a big reason this is so important to her is the future for her children.

“The fact that there is no affordable quality housing for my son coming out of college is extremely important to me,” she said. “That’s a pretty important thing, that they have a safe quality place to call home. It matters that people in our communities have a safe, quality, affordable place [to live].”

Gatewood herself has been recently housing-insecure. Her landlord is trying to end her lease in order to flip and sell her home at a higher price than she is paying. With six kids, just moving was never going to be easy. So Gatewood contacted her local tenant union, which at the time was Lexington Tenant Union. She had heard of them through a news article early in the pandemic, when there was great uncertainty for people out of work who needed to pay their rent.

Activists in the union got involved, looking over Gatewood’s lease and helping her advocate for an extension from her landlord. That release of pressure showed Gatewood the power of the tenant union, and prompted her to get involved with it.

Gatewood had run into a similar problem as Osborne with a housing voucher—the value simply did not match the cost of housing. Landlords were essentially free to deny her housing for lack of funds. This ordeal led to Gatewood getting involved with KY Tenants, a more policy-focused union, which she is currently working with, as well as the Homes Guarantee Campaign.

“Right now people are hurting,” Gatewood said. “They can’t afford the rent [with] the inflation. It’s tearing up households and homes because you have to make a choice between rent, medication, food, gas, and necessities to live.”

OSBORNE FOUND SHARING HER EXPERIENCE with the administration to be “very powerful.” And the announcement from the administration certainly reflected the work of the Homes Guarantee Campaign. But Gatewood and Osborne both believe the administration can—and should—do more.

“I personally felt like it was a step in the right direction, but it really doesn’t do anything to change my life today. I’m still paying double the rent,” Gatewood said of the announcement.

But there’s a sense in which the experience represented a victory, both for rental housing policy and for the movement that forced it into the discussion. By showing that they could get the White House to listen to renters—traditionally a group without the clout to get policymakers to pay attention—the Homes Guarantee Campaign demonstrated its value. That builds power among renters for the next stage of a long fight.

“It gives us a seat at the table,” Osborne said. “There is room to where we’re going to be able to work with them in the future. And we will definitely be organizing to make sure that the administration provides real relief for us and the other tenants across this country.”

The Homes Guarantee Campaign is proud of the progress and the work that a tenant-led movement can do to bring relief to people. The campaign is not going to stop pushing for the executive order, nor will it give up on tenants.

“We’re gonna continue organizing until we win rent regulations and real policy from the federal government to take on consolidation in the rental market,” Raghuveer said.