California voters passed Proposition 13 in 1978, greatly limiting both commercial and residential property tax revenue across the state, devastating the government’s ability to support education and other public goods, and fulfilling the neoliberal dream of shrinking the public sector. Other states soon followed suit, and the right was on its way toward its goal, in the words of Grover Norquist, “to cut government in half in twenty-five years, to get it down to the size where we can drown it in the bathtub.” The results were predictable. California went from seventh in per-pupil spending on education in 1977 to 39th in 2019. Educational outcomes plummeted as a result.

Commercial property tax reform in California, which requires a constitutional amendment, has been a goal of the left for more than forty years. Anthony Thigpenn has been organizing and building community power in Los Angeles for decades with that kind of structural reform in mind. He is one of the architects of a ballot initiative to reform Proposition 13 by requiring corporations to pay property taxes based on the current market value of properties. If the initiative passes, it would raise $12 billion annually and restructure the public sector in California. The measure would also help displace neoliberal orthodoxy about small government by affirming the importance of the things California families need to thrive: good schools and strong social services. The initiative is called “Schools and Communities First.” We talked with Anthony about how he thinks about mass political education, building power, and changing the narrative. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Jonathan Heller: The pandemic is upon us and has been causing huge disruptions. [Note: this interview took place before the uprisings after George Floyd’s murder. Anthony added a single paragraph referring to them afterwards, when he edited the transcript.] Do you see this as a moment in which positive change could emerge?

Anthony Thigpenn: Given the correlation of forces and power, I fear that economic elites, corporations, and right-wing politicians will take advantage of the pandemic to accelerate things they’ve been doing for decades: tax breaks for the one percent and austerity budgets for the rest of us, with cuts to education and the safety net. We also face an immediate threat to our democracy by way of voter suppression, gerrymandering, and control of the courts to disenfranchise more and more people. We’re likely to see more of these strategies, using the current emergency as pretext.

But at the same time, disruptions create possibilities. In times of crisis, social movements can make breakthroughs that might otherwise have taken years to achieve. The pandemic has already shaken our country’s ideas about housing, healthcare, the safety net, and education. The current crisis has allowed us to question whether we have a right to healthcare, housing, and income — and prompted many to rethink these things as public benefits, part of the social good. As a society, we’re also asking pressing questions about tax policy. As economic elites try to take advantage of the crisis and the bailouts for their own benefit, there’s an opportunity for the rest of us to demand corporations pay their fair share.

We’ve already seen the impossible happen. A year ago, it would have seemed unrealistic to imagine rapid, large-scale expansion of unemployment benefits or a freeze on rent payments. But when the economy is at risk, all of a sudden, the people in power found the money to subsidize those things. With so much in flux, there ought to be opportunities to make progress on other “impossible” things, like guaranteed income.

And now another crisis has emerged. The crisis of racism and police violence in the Black community. There is nothing new about the police violence that sparked mass protests. What seems new in this moment is the scope (the huge number of locations in the U.S. and around the world engaged in mass protests), the scale (tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of people in the streets), and the depth (multiple social movements, constituencies, and social sectors) of the protest movement. Racism has always been a core component of the dominant ideology. The mass protest movement that has emerged has the potential to move many social sectors to reject racism and embrace racial justice as a core part of an alternative narrative to neoliberalism and right-wing populism.

JH: This feels like a moment when we could change narrative, when a transformative narrative could become dominant. How do you understand the importance of narrative strategy in this moment and in general?

AT: On the left, our traditional methods for building power operate one person at a time. But we need to reach millions of people, and we’re not going to do that with one-on-one visits and phone calls, as important as those conversations are for the ends of community organizing. We also need to engage large social sectors, ideally millions of people, in challenging the dominant narrative, the ideology, and the values of the right wing and move people toward a more progressive left set of values and ideology. There are two dimensions to this work. First, the question of content: What narrative could resonate with people? Second, and equally important: What means and vehicles can engage larger social sectors of people around that narrative? Both the content and the vehicle are challenges for our movement.

JH: Let’s start with content. What stories should we be telling to move beyond the neoliberal worldview?

AT: The dominant narrative, based on right-wing ideology, incorporates a set of values like individualism, competition, and commodification. These elements create an ideological framework that influences how people understand their daily lives. As progressive activists, we can respond by advancing an alternate set of values — counter-values — like inclusion, the common good, mutuality, and dependency. We build on those values to create a narrative that celebrates the role of government and the collective “we.” As organizers, we encourage grassroots leaders to use these ideas as a lens for looking at the world we live in. It’s critical to challenge the worldview that undergirds people’s understanding of their experience and build a story based on alternative values: the common good, shared wealth, and shared prosperity.

Judith Barish: How do you know when it’s working? How do we figure out the messages that will convey these narratives?

AT: It requires experimentation. In the organizations I’m involved with, we talk about a caring economy and an inclusive economy. We talk about the common good and the larger “we.” We are trying to weave these elements into stories that appeal to people. One challenge is that often people want to craft micro-narratives directed at Black people, Latinx people, or women, but it’s equally important to share a common meta-narrative that both respects the experiences of all those different social sectors and ties them together into a larger “we.”

Community organizing is an ideal laboratory to figure out which messages work. As organizers do one-on-one conversations or hold house meetings, as they try to recruit people and move them up the leadership ladder, they can tell immediately which frames and messages are effective. If they resonate, people listen; if they don’t, they shut the door or hang up the phone.

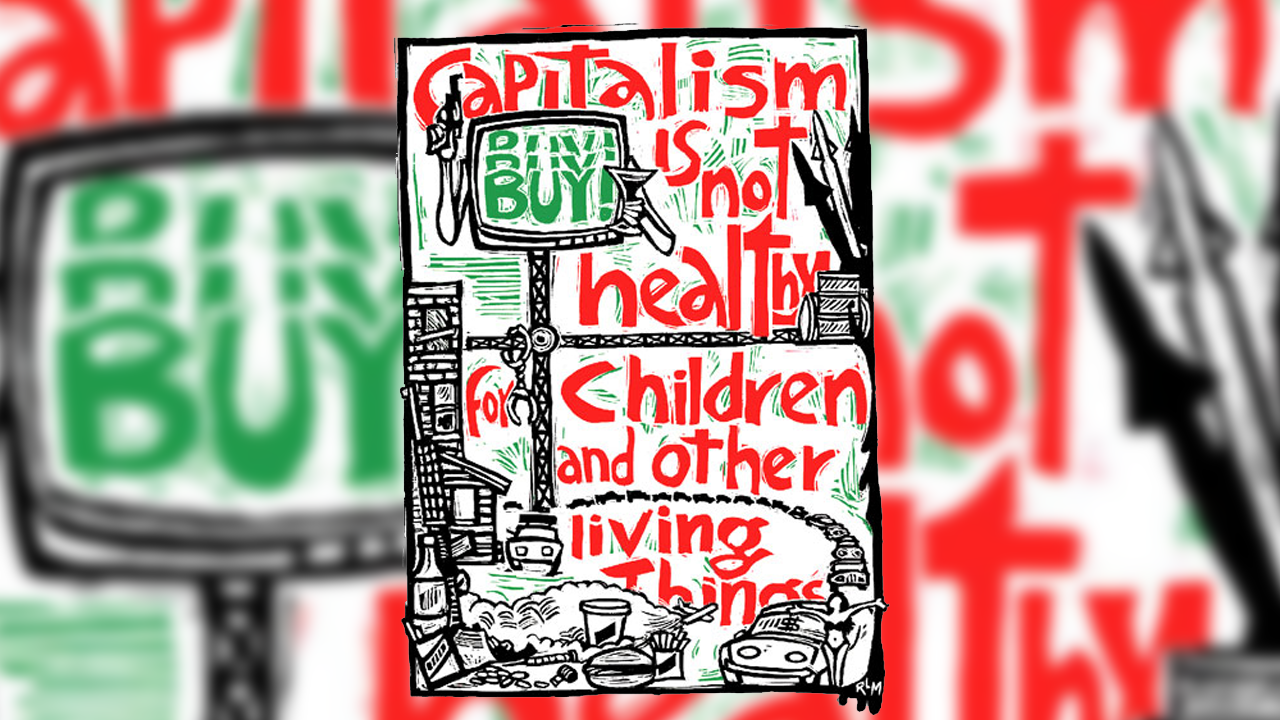

As we talk to people about politics and economics, we have to steer between two pitfalls. On the one hand, some of us on the left have a history of using Marxist jargon like “class struggle” and “surplus value.” We have offered brilliant critiques of capitalism. Our analysis has inspired professional organizers and a small group of people around us — but most people don’t get it. We are talking to ourselves. A successful narrative needs to translate those ideas into a language that resonates with people’s everyday experiences.

Traditional community organizing has the opposite problem. The Alinsky-style organizing model was explicitly non-ideological. Organizers trained in this school see it as a mistake to talk to people about structures of power and ideologies of change, so they try to mobilize people based on narrow, material self-interest. An entire generation of community organizers was trained in this method. These Alinsky-style organizing networks have been able to reach a wide scale, but at the cost of remaining within the dominant ideology.

Today, the organizations I work with are trying to get people to think bigger and move beyond narrow self-interest to a broader “we.” This bolder ambition produces a different kind of campaign because we aim to achieve broader structural change that embeds an alternative narrative within it. And we try to draw connections between these big structures and people’s personal experiences.

JB: You talked about changing the content of narratives, but you also mentioned that the vehicle has to change. I assume you mean that organizing strategy in general needs to change. Could you say more about that?

AT: Over the last few decades, I’ve been part of an effort to develop an organizing and movement-building strategy that differs from traditional community organizing in three interconnected ways.

First, as we’ve discussed, a lot of community organizers have shifted from narrow, non-ideological campaigns to an approach that takes aim at the dominant ideology. Instead of remaining on the terrain of existing ideology, we design and select campaigns that can help people see and dismantle the structures that impede them.

Second, we’ve made a shift to long-term thinking. Traditional community-organizing campaigns were small and tactical. They were designed to be winnable in the near future, so accomplishments were incremental — at the level of adding stop-signs on dangerous intersections. Today, I’m involved in several coalitions of organizing groups in California and across the country that are focusing on structural changes and planning five, ten, fifteen years into the future, developing a long-term agenda that helps us map out a sequential plan for transforming our state and country.

Third, we are consciously building a movement. Historically we’ve been trained to see other social movement organizations as competitors. Trapped in the non-profit industrial complex, we’re forced to compete with each other for money, credit, and territory. As a result, one theme of community organizing has been empire building. Building your organization meant making it bigger and better, in competition with other people and constituencies that ought to be colleagues. A theme of my work has always been to counter that. The essential thing we need to build are more powerful movements. Other organizations are part of the same movement: we’re not competitors, we’re allies.

JH: How has that evolution taken place in the work you’ve been involved with?

AT: I’ve been building coalitions and movements for decades, from AGENDA, which we started in 1993 with direct organizing in South Los Angeles, in the wake of the 1992 Los Angeles riots; to the Los Angeles Metropolitan Alliance, which brought in neighboring allies; to California Calls, which began in 2003 and is now an alliance of 31 grassroots, community-based organizations spanning urban, rural, and suburban counties across the state. At each stage, social justice organizations came together for greater configurations of power.

At every step, the theme of our work has been to get people to think bigger. From non-ideological to ideological; from small-scale and tactical to long-term and strategic; from empire building to movement building. Today, the Million Voter Project is a collaboration of seven statewide and regional community networks with 94 affiliates in 26 California counties. They share a common framework that includes ideology and narrative. This work is still experimental. Can we impact whole social sectors and win major structural change? That is yet to be determined.

JH: How and why did you arrive at the campaign to overturn California’s Proposition 13? [Passed in 1978, the ballot initiative Prop. 13 dramatically reduced property taxes for California homeowners and businesses — and made it very difficult for the legislature to raise them]

AT: Proposition 13 launched the anti-tax movement in the country. It was used explicitly by the right wing as a vehicle for “starving the beast” of government. So, in many ways, Prop. 13 and the tax revolt that accompanied it articulated very directly the ideological as well as the strategic imperatives of neoliberalism.

When I was organizing in South LA with AGENDA in the 1990s, we started talking about overturning Prop. 13. We saw the project as laying the groundwork for big structural change — one that would challenge both the power structure and the assumptions of capitalism. We did an analysis of the terrain to figure out, short of calling for socialism: what are the big structural changes that are a stretch but not impossible to do in a reasonable time frame? If we want to challenge the ideology of neoliberalism and put forward a different narrative, Prop. 13 seemed like a good place to throw down.

Talking about Prop. 13 allows us to talk about economic inequality and the role of corporations — and ultimately to question the idea that businesses deserve to take the surplus value for themselves instead of sharing it with the community. Today, taxation is the primary means for redistributing wealth in our society, so it’s vital to challenge the dominant view of tax policy: the idea that wealth is rightfully accumulated by the one percent and that taxes amount to “takings.”

The current effort on Prop. 13 started about five or six years ago, after we’d been working to build power across the state for several years. In 2015, California Calls went to unions and other community-based organizations and said, “Let’s take this on.” We agreed to seek a ballot initiative to force businesses and commercial property owners to pay their fair share of taxes, while continuing to protect residential property owners.

JB: How did you decide to frame the campaign as Schools and Families First?

AT: Activists, academics, and labor leaders had been talking about challenging Prop. 13 for decades. The main frame they used was the idea of tax fairness. It was a very wonky way of talking about the issue. When you’re talking about property tax reassessment and market rates, you very quickly get into the weeds. It didn’t resonate well with most people. It resonated with academics, union leaders, leftists, and movement activists because we understood how the existing law was a gift to corporations and reduced public resources available for programs that could benefit the rest of us. But people in our base communities, including communities of color, didn’t find it interesting or persuasive.

The polling around Prop. 13 reform was always very marginal. Major liberal institutional power players weren’t willing to make major investments in the campaign because of that polling. Our argument was that polling is just a snapshot of where you are right now, but after a multiyear campaign, people’s minds could change significantly. We studied framing and messaging that could change how people thought about Prop. 13 and an initiative to undo it.

One of the first things we found was the importance of talking first about what we stand for, not what we’re against. You can’t start by talking about the corporate villains. We learned to talk about the initiative by saying we’re for the social good. We’re for schools. We’re for children and families. We’re for local services. How do we get those things? By demanding resources from large corporations and wealthy landowners who are basically scamming us and failing to pay their fair share. So we reframed the Make It Fair Coalition as the Schools and Communities First Coalition and collected 1.7 million signatures to qualify for the November ballot.

We learned to lead with the issues and concerns people already had and then bring in the analysis. We started with what people were experiencing and then put that experience in a broader context. This is the work a narrative has to do.

JH: How did you use the campaign for narrative change? You talked before about changing the content and changing the vehicle. Is the Prop. 13 campaign helping you develop a new vehicle?

AT: Yes. The left is great at small-scale political education, but we haven’t been able to speak to large enough circles of folks or build sufficient power to make change. In California, the Schools and Communities First campaign is investing in public education (which in the past we would have called mass political education). We are using social media, paid ads, polling, and other avenues to figure out which values resonate with people and how to communicate at scale. We’ve raised about five million dollars in 501(c)(3) money for this. We want to see how much difference it makes. Can we reach a large enough group of people? Can we move people? We know we can do it with individuals, one at a time, but our current experiment explores whether we can do it at scale.

JB: What do you see as the opportunities in the current moment?

AT: Once the pandemic hit, many people, including our allies, encouraged us to forget Schools and Communities First. According to their logic, there’s no way people will be willing to raise taxes in a pandemic and a recession. It’ll be impossible to challenge the wealth of corporations in a moment when many corporations are being celebrated as helpers, opening their parking lots for testing. Some of our institutional allies and our largest donors believe we can’t win in November. They may be right.

But both the pandemic and the economic crisis have directed a bright light at the need for government. All of us need it. And we need other basic things — like housing and healthcare — which shouldn’t be at the mercy of market forces. This is an opportunity to point to structural changes in housing policy and healthcare, which our opponents previously said couldn’t be done because there was no money. But all of a sudden, when it’s clear that it’s necessary, the money can be found. These are opportunities we are trying to figure out right now.

In November, California voters will decide about Schools and Communities First. As we work on that campaign, a larger configuration of organizers, activists, and progressive leaders are holding conversations about an agenda we might be able to accomplish in the short run. Can we win two, three, or four of our top priorities? As a movement, we’re trying to converge on three or four policy goals — changes in healthcare, housing, or jobs — that we couldn’t have won six months ago but might be able to win in the current moment.

JH: You talked about setting long-term goals. How are you thinking about what’s next and how to build power for the long run?

AT: The Million Voter Project has spent the last year working with Grassroots Policy Project to figure out our long-term agenda. We don’t want to put all our energy into Schools and Communities First, win or lose, and then wake up after the election and wonder what to do next. Instead, we are trying to figure out the sequence of structural change battles for the next five or ten years, to be able to make the kind of transformations in California we think are necessary. We know the issue areas: housing, healthcare, education, immigration, and so on. Now we’re trying to figure out not what our next short-term, tactical battle is, but what the big structural battle is. In this moment of crisis, we may be able to win in two years campaigns that we thought were on a five-year horizon. But what about after that? What about five or ten years from now? What are the changes we want to win? And what’s the power we need to build to win them? We’re trying to conceptualize that power in multiple ways, from the perspective of traditional community organizing, base building, mobilizing, creating a united front, and the institutional players we have to move. And we have to conceptualize power by talking about narrative: what ideological power do we have to build to be able to win our agenda?

There are clear limitations to the old way of doing things. But things are changing. My advice to organizers: continue seeing narrative and ideological power as a central part of the power we have to build to bring the world we want into being.