Over the last four years, the term “resistance” has become popular with a new audience: white women, the majority of whom were not involved in the movement for civil rights and racial justice before November 8, 2016. They have used #TheResistance to describe their organizing in response to the election of Donald Trump. To these women, I have frequently said, “Welcome. Let’s get to work,” because Black and brown communities have been part of a resistance against white supremacy and systematic disenfranchisement for generations.

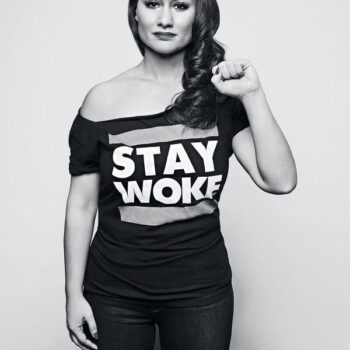

I was one of four National Co-Chairs of the 2017 Women’s March on Washington, the largest single-day protest mobilization in U.S. history — and the event that, for many, inaugurated this modern-day “resistance.” I was brought on as a leader after the initial women who spread the idea — all of whom were white — co-opted the name of the Million Women March, which was organized by Black women in Philadelphia in 1997. They unintentionally played into a long and painful history of white women trying to dominate feminist organizing, and they reasonably feared that the march would be met with significant counter-organizing by women of color.

When my sisters Linda Sarsour, Tamika Mallory, and I agreed to step in, we brought an ideological commitment to centering Black women in our leadership and our priorities. As a Chicana feminist who recognizes that Black feminists created the frameworks upon which we all build, I wanted to ground the march in Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of intersectional feminism — not just as a theory but as a practice. My fellow co-chairs and I fought to put women of color and immigrant women at the center of the march, provoking challenging conversations with white women organizers in the larger Women’s March network. Some white women did not understand why we insisted on expanding “women’s rights” beyond reproductive rights and equal pay to include issues like police brutality, immigration, lack of access to health care, and workplace harassment — issues that primarily affect Black and brown women.

This work was difficult and emotionally draining, but the unprecedented size and breadth of the five hundred-plus organization coalition we built was one of the keys to the success of the 2017 Women’s March. Creating language around our core principles and values was essential to building the trust we needed to bring on so many partners. Women of color knew marching “against Trump” was not sufficient in a country operating on over four hundred years of systemic white supremacy. We needed a united statement of solidarity around the principles that we were marching for.

My fellow co-chairs and I invited over forty women movement leaders, including many women from marginalized backgrounds, to draft Unity Principles that would guide the March. We had to mediate deep divides in the process. For example, we had to affirm both women’s right to engage in sex work and their right not to be trafficked for sex. This was more complex than just writing a couple sentences to include both — the organizations and individuals in each movement deeply disagreed with specific positions the other was taking. At one point, an influential feminist persuaded someone with access to the document to erase sex workers from the statement altogether. In response, I worked with activists from the sex workers rights movement to strengthen the language around respecting their rights and autonomy.

Building bridges between communities that usually work in isolation is difficult but necessary to creating a unified, unstoppable force for change. To draft the Unity Principles, we had to consistently bring the conversation back to our shared goals while encouraging everyone to put aside hard feelings, old resentments, and ideological differences that fell outside of our common mission. Building consensus around the document allowed us to ensure that a range of voices were included in the programming at the march — and ultimately contributed to the record-breaking turnout that year.

I believe we also created a lasting cultural shift, although the work is far from over. Women’s political organizing — especially the labor of women of color — has become more visible, and more women of color and trans women are taking office than ever before. Just this year, we saw the first trans women elected to state and local office, the first Indigenous women in Congress, and the first Black and Asian woman sworn in as Vice President.

These victories come with the bittersweet knowledge that organizing for change always comes at great cost to women of color and women from marginalized backgrounds. We carry increased burdens, from the toll of emotional labor to the inequities of resource allocation to the increased threat of violence from a white supremacist society that is alive and well. The pressure has a significant impact on us, no matter the level of excellence we are able to maintain. As Biden takes office in the wake of a white supremacist insurrection at the Capitol, we need to invest in the leadership of women from marginalized backgrounds, who best understand how interlocking systems of oppression are operationalized — and how we might dismantle them.

One lesson I learned from the Women’s March is that if we welcome the opportunity to learn about the struggles of other groups, as well their gifts and their humanity, then we can build the unity that will allow us to make transformative change. At the root, strong relationships are what allow us to show up in solidarity and form robust coalitions. Building these relationships requires accountability; we don’t need to agree on everything to build unity around a shared vision, but we do need to hold space for the discomfort that is necessary to make amends for harms done. I center healing in all of the organizing work that I do because we cannot build strong coalitions unless we’re committed to healing our wounds — and our wounds look different.

The Women’s March was the introduction to activism for many women, but I hope that our white women allies — who’ve been a proud part of “The Resistance” over the past four years — don’t hang up their protest signs now that Trump is out of office. As we move into a new era, I hope we all remain committed to the work necessary to build a truly intersectional coalition that transforms this nation.

Read the issue: Debriefing the Resistance