On February 22, 1980, workers at the Greyhound Burger King in downtown Detroit won the first union election at a fast food restaurant in the United States by a vote of 25-23.

Lena Halmon, a cashier and leader in the drive, told the Detroit Free Press that the workers “had been ready for something like this…[and] were upset because so many of them are treated with disrespect. We’re not children anymore. The managers should treat us like the young adults we are, instead of screaming and hollering.” A co-worker, Beverly Passmore, added, “The reason I want the union is not only to better things for the employees there now, but also to better it for the people yet to come. Hey, I got little brothers and little sisters. They will come here and get pushed around, treated like dogs. I want them to RESPECT us. Let them treat us like people, not animals!”

Halmon and Passmore were both members of the Detroit Fastfood Workers Council of the United Labor Unions (ULU) Local 222, an outgrowth of the national community organization ACORN. ULU was intent on organizing the over 5,000 fast food workers across the city and had organizers on the ground for several months making contacts, mapping workplaces, and doing house visits. We thought we could organize all 5,000 workers through the procedures of the National Labor Relations Board. We learned the hard way that we were wrong. Organizing fast food workers proved to be a huge undertaking, but the lessons we learned and the models we developed ended up helping us organize tens of thousands of low-wage homecare and childcare workers — and informed the Fight for $15 thirty years later.

We Were Young, But We Were Fast: Organizing Store #768

In March 1980 — just after the Greyhound Burger King victory — I set out to organize the Burger King on the corner of Michigan and Martin on the southwest side of Detroit, known as store #768. Most of the workers were in their late teens and early twenties, with a core of older workers; the vast majority were Black and brown, though there were a handful of white workers. All of the workers — no matter how young — used at least some of their paychecks to support their families. It never ceased to amaze me how many families depended on that fast food check.

To build up our list of workers inside the store, we went around with petitions to raise the minimum wage and improve bus transportation. Building the list was tedious and repetitive but necessary. And it taught me a key lesson: it’s all about the list and building it in any way possible — finding it in the dumpster, developing it at the stores and on visits, or liberating it from an employer.

We estimated there were 25-30 workers in the store; at each shift change, only five-to-ten workers would come off. We had to work fast to catch the workers as they came off shift. We’d catch up with them at the bus stop, on their way to their car, or walking home. I remember finishing my rap with one group of workers and then sprinting after another worker walking home. After a while, I tried a new technique and went right up to the worker at the register, gave them the petition to sign, and asked them to have everyone in the back sign it as well. Sometimes, if I got there before the supervisor, it worked. One time, I got about seven signatures with addresses and some phone numbers.

I took the list and started systematically house visiting the workers. Fast food workers, regardless of their age, tend to be a very mobile group and require lots of house visits to catch them at home. I would usually be out for at least four-to-six hours every day hitting the doors or talking to workers at shift changes. I had large blank sheets of newsprint paper with all the names of the workers on the various shifts and how many times I’d attempted to reach them, with a voter identification — yes, no, or maybe — next to their name.

One of the first workers I caught at home was Lennon, a young Black worker just out of high school. He helped sketch out the names of the workers and gave me a feel for the dynamics and demographics in the store. He knew a lot about the store, but I couldn’t tell if he was seen as a leader by his co-workers. Another worker who stood out was Cathy, a white woman in her thirties who had several kids. Her husband was a laid-off auto worker whose unemployment was about to run out, so her paycheck from Burger King was going to be the only income in the home. Cathy was older than some of the other workers in the store. But, like Lennon, she seemed to know who was who. She helped to fill in the blanks on the names and shifts of a number of workers. Both agreed to do visits with me.

After a few weeks of house visits, we decided it was time to hold our first Organizing Committee (OC) meeting. Cathy volunteered her house, which was just a few blocks from the store. We called everyone we’d visited and invited them to the OC, but only one other worker showed up. Still, we plowed through the agenda. They identified everyone they knew in the store, their shift, and what they thought about the union. They also identified who the supervisors were and warned me that Burger King Corporate had recently installed a new Black supervisor, Wendell, who they were suspicious of.

We voted to organize and begin signing up members on union cards. We only needed thirty percent of workers on cards to hold a union election, but we agreed we wouldn’t move forward unless we had at least seventy percent on cards; that meant we needed about 20-21 cards to move forward. Everyone signed up to do house visit shifts with me and took cards to ask their co-workers to sign up.

Soon, the cards started pouring in. We hit five cards, then ten, then 15, then 17. When it started slowing down, we went against our instincts and filed the cards with the Labor Board, even though we hadn’t hit seventy percent and didn’t have an organizing committee that was representative of the workers at the store. We figured the sooner we got our election, the sooner we’d win, and if we wanted to win more elections, we’d have to be willing to take more risks. We filed our cards with the NLRB and got a quicker election date than we thought: May 28, 1980.

Big Mac Attacks

In addition to the Greyhound Burger King, the ULU was also organizing three Ralph Kelly franchised McDonald’s stores on the north side of the city, which we hoped would build the momentum for our Burger King 768 election. At the Kelly stores, we had early super-majority worker support, great leadership, and intense interest among the workers. But McDonald’s and Ralph Kelly quickly teamed up with an outfit called “New Detroit,” a corporate-funded front group formed after the “riots” in 1967 to “save Detroit” — that is, to reshape the city in their corporate image. That meant no unions, especially in fast food.

Kelly and the McDonald’s Corporation began their campaign with an A-team of former Special Forces psychological warfare specialists they had flown in from their corporate headquarters in Chicago. For months, they systematically profiled every worker and interrogated, intimidated, and harassed each one. They also fired several union supporters. Daily mailings, anti-union flyers, and captive audience meetings were the rule.

We fought back with our own newsletter, “The Fastfood Worker,” along with flyers, meetings, and direct actions, which got great press coverage. We even had our own self-taught cartoonist, Michael, who used the pen name “Pay More.” Our final mailing — “Why We’re Voting Yes” — had pictures and quotes by a strong majority of the workers who supported the union.

But McDonald’s pushed back even harder. The climax of the company’s campaign included a “McHappy Day” party, a few days before the vote, hosted by none other than Ronald McDonald himself. No expense was too small to beat the union: they paid every employee to come to the mandatory party, staffed the restaurants with workers from other stores, bussed in all the Ralph Kelly workers to a central banquet hall, prepared a full course meal, and hired the most popular DJ in Detroit, “Marvelous Marv,” to spin the tunes. They even had a “special guest:” Houston Oilers running back Earl Campbell. The high point of the night was the “McRaffle,” in which everyone won a cash prize; we heard no one won less than $50, with some pocketing much more.

The corporation also launched an air war targeting the public, the Black media, and community organizations — and portraying the union as white, out-of-town carpetbaggers. Bill Johnson, a Black reporter who attended one of the company’s press briefings, later summed up the real reason New Detroit held the meetings to the Detroit News: “ACORN makes it difficult for them to control community organizing. ACORN is able to generate a lot of support in the face of established [New Detroit-funded] organizations because these organizations haven’t been doing anything….”

The “white outsider” arguments were especially ludicrous for the lily-white McDonald’s Corporation, headed by Ray Kroc, himself a target of innumerable lawsuits and charges of racism. The fast food worker-leaders were supermajority Black and brown, we had a diverse organizing staff, and prominent Black union officials and city council members stood by the union’s side, but the McDonald’s corporate campaign was overwhelming. All told, the company spent well over one million dollars. On May 1,1980, the union lost 104-46.

Management at the Burger King #768 used a similar campaign of interrogation, mandatory captive audience meetings, harassment, and intimidation along with an anti-union air-war to beat down our majority. But I remained confident. I kept in touch with Lennon, Cathy, and Peggy, as well as a few other strong yeses we had picked up. We prepped for the captive audience meetings, and Lennon and Cathy reported back that the workers had stood up to management. Management — especially the popular new supervisor, Wendell — was definitely turning some of our yeses, but I believed we were retaining our majority.

Every day for the last two weeks before the election, my head organizer, Danny, kept pressing me for my yes, no, maybe, and membership numbers, until finally a few days before the election, he asked me point blank: what did I think we’d win the vote by? I told him that my count was still 18 yeses, ten no’s, and some maybes. Danny was skeptical, but it seemed air tight to me.

On the day of the election, I paced back and forth in the plaza outside the federal building, while Danny and Mark Splain, the national Chief Organizer, observed the vote count. After a while, they emerged from the federal building. We’d lost 21-1. I hadn’t even kept all three rock-solid yeses: Lennon, Cathy, and Peggy. I went home and collapsed on the couch in my apartment on the southwest side of Detroit. I felt like that old BB King song: “No One Loves Me But My Mother…and She Might Be Jivin’ Me, too!”

Learning to Lose, Learning to Win

One year later, in May of 1981, workers at the Burger King 768 decided to organize again. The Corporation had tried to “grind them out” — industry jargon used by management to describe how they “ground out” the workforce like they ground out burgers. The company had also fired Wendell — the popular supervisor who led the Vote No campaign the year before. He was replaced by some mean white supervisors from the suburbs. The uproar Wendell’s firing caused showed me how much influence a “good” supervisor like Wendell could have on the outcome of a union drive, something I never would have predicted.

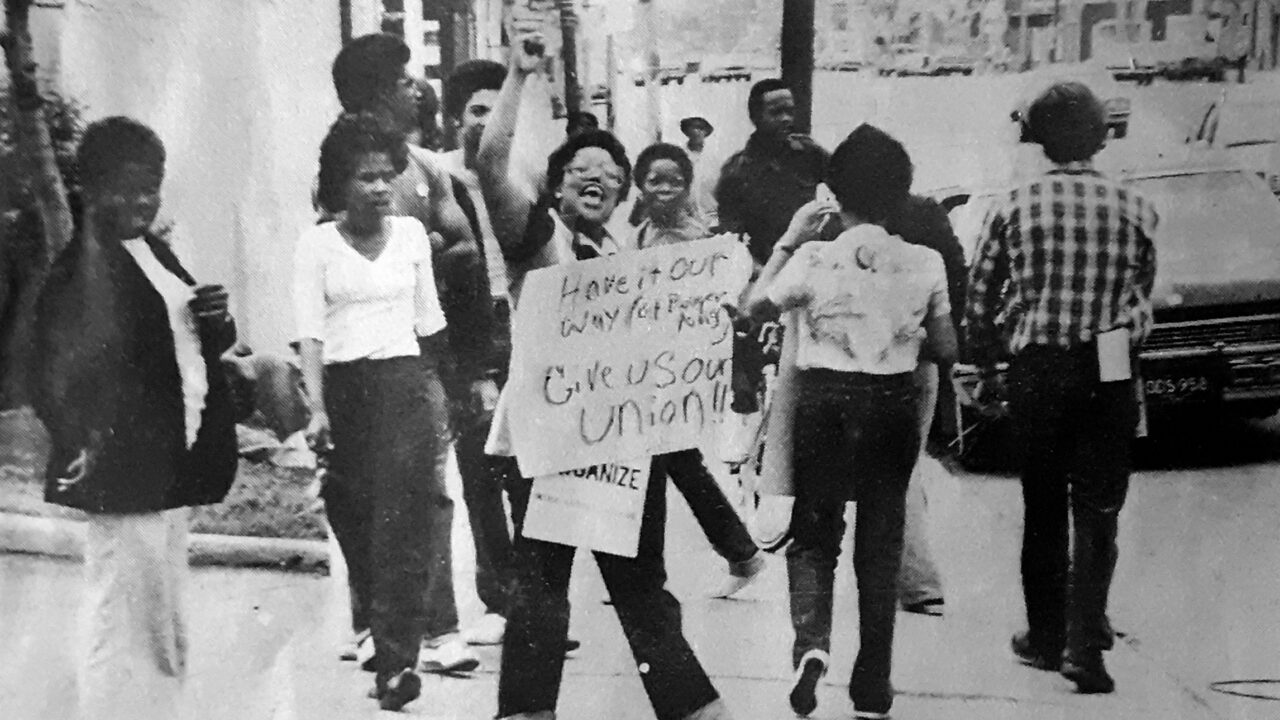

We agreed to help these courageous workers — all of whom had voted against the union the year before — to reorganize. They signed up a supermajority on authorization cards, then seized the store during a recognition action, holding it until management brought in the police. After a standoff with the police and supervisors, we picketed in front of the store, totally shutting down business and gaining support from the neighbors, who were all pro-union. We went downtown and filed for an NLRB election that day.

The Burger King corporation knew we were heading for an overwhelming win and fired some of our leaders outright. They then “sold” the store right out from under us to a “franchisee” who chose not to hire almost all of our folks. The “franchisee” had been employed by Burger King corporate’s human resources department right up until the day they “sold” him the store. We filed charges at the Reagan Labor Board, but lost most of them, and the Labor Board allowed the phony “sale” to go through. The second organizing drive taught us another hard-fought lesson: fast food corporations will do everything in their power to beat the union, even falsifying paperwork, “selling” a store, and lying about it all at the NLRB.

We kept organizing, and barely two years later, in early 1983, the NLRB ordered Greyhound Food Management (GFM), the largest Burger King franchisee in the U.S. at that time, to negotiate with ULU Local 222. Over a period of several months, Greyhound Burger King workers sat across from the GFM corporation and negotiated the first fast food union contract in the United States, guaranteeing wage increases, increased shift differentials, health benefits, paid time off, a union shop, a grievance procedure, and many other improvements. The victory was sweet but temporary. In the mid-1980s, Greyhound Food Management decided to leave the fast food business and closed all their Burger King restaurants in their terminals. The workers in Detroit all lost their jobs.

I had already left Detroit by that point, moving to Chicago with my partner Madeline Talbott, who was opening up an ACORN chapter there. In 1983, I founded ULU Local 880, which began organizing private and public sector homecare and childcare workers. We affiliated with SEIU in 1985. ULU/SEIU Local 880 grew from only seven dues-paying members at its founding to over 70,000 by 2008, when it merged with two other Chicago SEIU healthcare locals. Today, SEIU HCIIMK represents over 90,000 workers across four states, the largest union local in Chicago, Illinois, or the Midwest. Along the way, 880 developed public and private sector homecare and childcare organizing models that eventually brought hundreds of thousands of homecare and childcare providers in over 15 states into SEIU. Today, the two million member SEIU represents over 600,000 homecare and childcare providers.

The Fight for $15

When I started organizing fast food workers in Detroit, I had barely six months of community organizing experience. In Detroit, I learned a number of critical lessons that informed the rest of my organizing career — and gave me the skills to build a fighting union of homecare and childcare workers, a task which many predicted would be impossible. First, I learned how much I still needed to learn about the basics of organizing: relationship-building, listening, house visiting, collecting dues, and doing “organizer math” to assess my yeses, nos, and maybes. Even once I learned these skills, I still struggled to win using the NLRB model. There were good reasons why we went through the NLRB in 1980, but the corporations beat us too often using the NLRB. If we did a rerun today, I would build through membership recruitment, organizing around high-profile issues and campaigns, and direct actions, including strikes. While we did hand-collect dues in Detroit, we were not as disciplined and systematic about it as we later were when we organized homecare and childcare providers. My experience in that union — building strength through membership conversations, growth, and direct actions to win local and state legislative victories around wages and benefits — convinces me that this is the better way to go.

In 2011, thirty years after my loss at Store #768, I was asked to write a memo and do an organizer training about fast food organizing for Action Now in Chicago, which I then shared with New York Communities for Change (NYCC). Both organizations were embarking on their own fast food organizing drives — what would later be known as the Fight for $15. We still have a hell of a fight in front of us to win justice in the fast food industry, but we are closer than ever to winning fairer wages, thanks to the bravery, determination, and creativity of many organizers and workers, in Detroit and beyond.

Acknowledgements

The fast food organizing in Detroit — and future homecare and childcare organizing successes — would not have happened without the bravery, skill, and commitment of the members and staff of the United Labor Unions. I will be forever grateful for all of them for teaching me so much. Among the many: In Detroit, members and leaders like Lena Halmon, Beverly Passmore, and Keith Rohman at the Greyhound Burger; members and leaders Stephanie Collier, Wendell Jones, and Michael Bynes, head organizer Danny Cantor, national organizers Charlie Rose and George Gossett, field organizer Jerry Johnson, field organizer Pam Bell on the Kelly’s McDonald’s stores; members and leaders Lennon, Cathy, Peggy, Cynthia Diane, Luther, Valencia, and field organizer Dale Ewart on the Burger King store #768 drive and rerun; national staff from Boston, including Chief Organizer Mark Splain, National Lead Organizer Barb Bowen, Field Director Mike Gallagher, Lead Organizer Maureen Ridge, and later, on the homecare organizing, Kirk Adams. The Boston leaders and staff later made huge breakthroughs in organizing the biggest private sector homecare agencies in that city; they organized thousands of homecare workers under contract by the time of the merger with SEIU in 1984. Mark later became AFL-CIO Organizing Director; his partner Barb Bowen served in many key capacities with SEIU and the AFL-CIO before her passing. Mike Gallagher and Maureen Ridge served many years as senior organizers with SEIU and the AFL-CIO and worked on many iconic campaigns organizing tens of thousands of workers.

Danny Cantor later worked with Kirk Adams and Cecile Richards organizing hotel workers in the New Orleans local with Wade Rathke. Danny later went on to become one of the founders and National Director of the Working Families Party in New York City and today is co-chair of the WFP National Committee. Kirk later became a national Executive Vice President of SEIU and today is Director of the Healthcare Education Project. Cecile Richards later served as the national President of Planned Parenthood and today is a cofounder of Supermajority, a women’s political action group. Dale Ewart is a Vice-President of 1199-UHE, SEIU, in Florida. Myra Glassman was the first field organizer I hired in the Chicago ULU Local 880; she led many organizing drives and trained countless organizers. Today, she is a Vice-President of SEIU Local HCIIMK. Last but not least, I want to thank the hundreds of unnamed courageous fast food workers we touched — and who touched and educated us — at the many other fast food stores in which we had drives, including White Castle, Burger Chef, Dunkin Donuts, Arthur Treacher’s Fish and Chips, Kentucky Fried Chicken, and corporate and franchised Burger King’s and McDonald’s.