The Forge: What’s your background, and how do you relate to culture in organizing?

Rachel: I grew up in New York City, in a secular Ashkenazi Jewish family that I characterize as fallen owning class. I entered social movements through Occupy Wall Street, locating my work in the lineage of NYC cultural workers in and around Jews for Racial and Economic Justice and especially my mentor Jenny Romaine. Previously to movement work becoming my paid work, I was an elementary school art teacher, and I first honed my craft as a visual strategist by coordinating art for the People’s Climate March and other mass mobilizations, mostly in the climate movement.

I have always made things with my hands as a way to make sense of the world, and I believe that making visuals together is a strategic tool for coalescing collective energy. Building power means coming into understanding that what we say together is more meaningful than what I say alone—and making art together makes that process very concrete, accessible, and embodied.

Josh: I grew up in central Pennsylvania during the war on terror, and the beginning of the war on immigration. Most of my cultural work is a response to seeing that media blitz of paranoid patriotic unity. Lancaster is an immigrant city that takes in a lot of international refugees in a deeply conservative county. Marches and rallies were a way for the communities I grew up in to say “we exist in a different reality from the news.

My background is in graphic design, photography, and some street art. My work centers on supporting communities that are being inaccurately portrayed, to help them speak and feel seen in the street on their own terms.

Look Loud is the name for our collaboration. We formalized that about 3 years ago. Before that, we’d each spent about a decade fielding calls from organizers the night before a march asking us to paint a banner. Often as an afterthought. We focus on working with campaigns and communities to develop slogans, objects, tactics, and cultural strategy that can speak as precisely and powerfully to the public. We also spend a lot of our time driving to and from actions, and packing and unpacking gear from our cars.

The Forge: How have you used arts & culture in organizing since October 7?

Rachel: We got pulled into this organizing just a few days after Oct. 7th, when we got a call asking if we could help make enough art for 2000+ people to take emergency action in DC in the next 48 hours. The political imperative we heard on strategy calls was to push the word “Ceasefire” into the public arena. At that moment, not even our most trusted electeds were saying it. I remember saying— “sounds like we’re going to need some banners that say ‘ceasefire’ on them, yes?” So we worked with our comrade Cesar Maxit to make a grip of black banners that just said “Ceasefire.” IfNotNow used those banners to block every entrance of the White House, and then those same banners were passed around DC –– used by JVP, Rising Majority, others. We also helped build short-term shared infrastructure for producing more signs and banners: we gathered up a ton of art supplies, helped locate a church that could be art-making HQ for a week, got in touch with more people with visual production skills –– Rachel London, Sarah Sills, Nina Eichner, Izzy Harrison, Cesar who I mentioned already, and connected them to each other and to the organizers who needed their help and also had access to emergency cash to keep buying paint.

I think about our work as a balance of visualizing urgency, and visualizing investment. In the early days it was all about urgency, and over time that shifts. One obstacle for much of this winter was that it was very difficult to face the reality of the long struggle we are in. I remember about a month before Chanukah– being in conversation with Jewish organizers and saying, “We all know that in the US Chanukah is actually about Christmas. It’s the holiday where American Jews grapple with our ambivalence about assimilation and our relationship to US Christian hegemony. We cannot miss this moment to point our people towards facing the fact that the US is enabling mass death by telling the lie that that makes Jews safe. That’s not what we want our government to do for Jews.” And no one could make a plan, simply because we could not bear that we would not have a ceasefire by Chanukah. I kept texting this dumb sketch I made of a menorah with the letters “ceasefire” on it to any Jew who reached out to me… until a week before Chanukah, Rabbis for Ceasefire finally called and asked me to build a giant Ceasefire menorah. They’d had exactly the same idea.

Josh: We’ve been supporting a lot of faith organizing, mostly by the younger or more rebellious members of the community organizing their clergy and elders into joining them. So it’s very important to them to turn the streets into an authentic place of worship that their elders can be organized into. There’s a really beautiful “I learned this from you” moment going on between young political courage and older moral grounding through replicating traditional arts & culture in an escalated political space.

Early on we were producing a lot of patches for Muslim organizing. Traditional protest signs don’t work during Muslim prayers, but back patches let a crowd of kneeling bodies maintain control over their message.

We do a lot of banners that look like the ornate windows of churches, synagogues, and mosques. Also banners that mimic the fabric on altars and religious garb. When we bring that into the street it creates the architecture of a house of worship around us. It helps people see the event as a prayer service that contains political messaging, as opposed to a protest that contains a moment of prayer.

My background is in the Mennonite church, which has a history of anti-occupation organizing in Palestine. So we’ve been doing a lot of quilt banners for Christian organizing. Quilts are an object that’s traditionally made for relatives or members of the community. Placing the, frankly painful, messaging and images on quilts fuses it with a sense of community service and endurance. Arts & Culture like this help people to express their objection to the occupation as a part of their commitment to acts of service and community values, especially people who don’t feel well versed in “debating politics”.

Rachel: The work we’ve done with a variety of Faith communities started with responding to asks from local organizers in both our home towns, and to national asks from our peoples –– from Mennonites and Jews –– in a moment where everyone does what they can to bring their people to the street. Big moments of new movement growth always lead to lots more people painting banners and we’ve also just been supporting that –– sharing supplies, work space, and production tips. It’s a moment for me to keep honing my skills in accompaniment and mentorship.

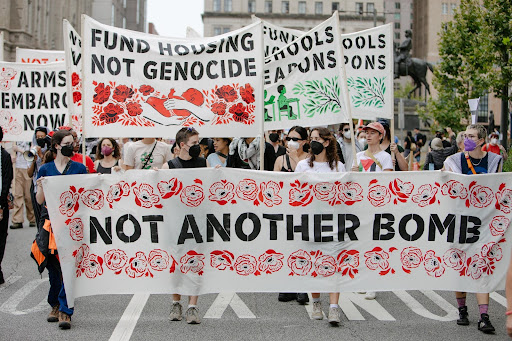

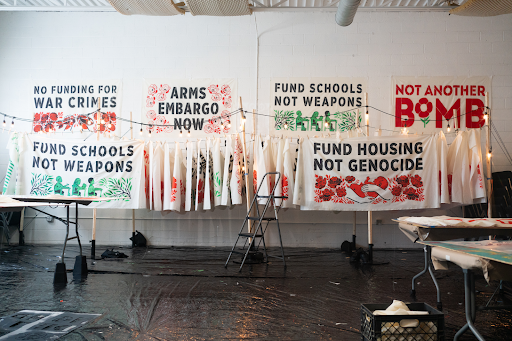

We spent most of the summer getting ready for August 18th’s Not Another Bomb day of action. We supported Palestinian organizers in Dearborn and Detroit, Michigan to make more than 300 copies of banners that were designed with leadership from the national Uncommitted movement. We shipped those banners to actions that happened across the country, and used photos of our art-making to inspire and coach other sign and banner makers associated with the 80+ actions. Uncommitted’s assessment is that we need to shift our movements to Arms Embargo as a primary demand, and to use the phrase “not another bomb” as frequently as we use the phrase “Ceasefire Now” because an Arms Embargo is an actionable policy that we need in order to achieve a Ceasefire. These banners are an intervention that very concretely supports our movements to make that pivot.

The Forge: How does art & culture relate to the kinds of marches and sit-ins we’re seeing now?

Josh: On a basic level arts & culture are good tools for setting the narrative. In the early months I was seeing a lot of news outlets refer to demonstrations by the words on the banners. For example, traffic reporting (which is not traditionally friendly to highway blockades) saying “protests to Let Gaza Live” as opposed to “protests against Israel.

On a deeper level, the point of cultural organizing is that not only are communities made up of people who individually think they’re the only one who cares about an issue. They individually think they’re the only ones who identify as part of a community or culture. For example: if capitalism has eaten up our neighborhood and now there is no longer a neighborhood pride or culture, it’s hard for people to feel like they belong to a voting block that can exercise political opinions.

A lot of organizing right now is centered on supporting various constituencies to just believe we exist, so that we can begin to believe that we could exist as a political block. That we are a community that attends marches and rallies. We’re fighting with our opponents over which group represents mainstream Jews, mainstream voters, mainstream working people, veterans, Christians. Art and culture are some of the most powerful tools for claiming that our 500 people in the street represent a broader constituency. Right now that looks like prioritizing patterns, iconography, and symbols of who we are before using generic images of bombs and death (that signal very little about who is speaking). Also using chants, songs, and terms that have roots in the communities that are mobilizing.

Rachel: A pillar that has made this global movement possible is the incredibly robust visual vocabulary of Palestinians self-determination which has been built over generations in Gaza, in the West Bank, and in the diaspora by Palestinian artists and cultural workers. After October 7th, the global public was able to immediately pick up the symbolism of the keffiyeh, Palestinian flag, poppy, watermelon, key, olive branch –– and so the whole world was able to communicate solidarity. Watching this expand so rapidly and effortlessly has been a huge affirmation of the critical role that visual culture has in building power, the critical contributions that cultural workers play in ideating, producing, and replicating imagery that enables social movements to proliferate and hold attention.

Where we see our movements struggle more is in making our demands as easily replicable as our solidarity. What else do we want, beyond a Ceasefire? If and when a Ceasefire happens it will be a massive deflation of public anxiety and the spotlight will not be on our movements, so we need to spell out the next steps now if we want the public imagination to come with us to the places we urgently need to go.

Josh: In our work messaging pivots take 3 months. That’s how long it takes a community to see their peers using new messaging, become confident using it, and have an opportunity to use it. Like Rachel is saying, a natural pivot from ceasefire to ending the occupation can and needs to be built into our cultural visions and messaging now. If we wait until the ceasefire, we’ve committed to months of demobilizing before most of our people feel ready to engage again. Everyone moralizes that delay and thinks that their community will be the exception. But in our work, pivots almost always take 3 months.

The Forge:Toni Cade Bombara says “it is the job of the artist to make the revolution irresistible.” Is this something you think about or apply to your own artistic process, practices, and/or strategy?

Josh: Most of the time my role as an “artist” is to increase attendance at a march, help disseminate new messaging, or improve training curriculum with images. That’s all to say that treating “art” as special from other community organizing skills helps nobody.

But there’s a lot of wisdom in choosing “irresistible.” As opposed to making the revolution feel winnable, or safe, or morally grounded. It keeps us asking which one of those things is important to our audience. It keeps us curious about the audience. Leaves no room for us to moralize aesthetics. Do the details of our work need to be perfect? Scrappy? Urgent? Respectable? They need to be done just well enough to keep the revolution “irresistible.”

Rachel: I’d agree with you, Josh, that the most meaningful part of this quote is the opportunity to define what “irresistible” means to our people. It’s been a journey for me –– as a person with a very… let’s say distinctively power-clashing personal style –– to really ground in what it means to treat visuals as a component of strategy. To move beyond what I personally like and be able to decode what different constituencies I’m supporting find irresistible. There’s a sentimentality in the way U.S culture sets artists aside on a pedestal that’s actually quite neoliberal. We’re taught to see individual creativity as a cause –– we celebrate it and fight for it –– instead of as a tool that helps us win other things.

When we’re working on developing visuals for movements or campaigns, we ask our partners to start by articulating the goals of the visuals: is it the target that most needs to be moved by the image we project to the world, or is it the base, or the public? How do we want our audiences to feel when they see the work? What kinds of reactions will help us win what we’re here to win? Often brilliant organizers we work with have many visions of art we could make, but not a very developed muscle for discerning how those cool ideas relate to their own strategy. Our craft is to understand how to translate abstract goals into concrete visual choices.

The Forge: What kind of narratives and messaging do people most need to hear right now?

Josh: There’s two ways I look at messaging, especially in the street:

Messaging is the repetition of phrases and associations to our audience until it’s involuntarily absorbed. Think Coca-Cola’s advertising. We’re doing a lot of this with facts about the genocide. Associating Israel to apartheid. Associating military aid to massacre. Associating Palestine with its right to exist.

Or, messaging exists to establish something unexpected about who is speaking, that allows us to connect to it on a deeper level. Jews speaking against the occupation are doing this. Veteran organizing is doing this. When a Palestinian social media account posts about just wanting a regular wholesome life they’re doing this.

We need both. But we specifically need to invest more in the second. People are paying attention to which groups are saying what right now. That’s what gives us an opening to cut through the noise.

Rachel: Yes. What’s missing right now for the many of us in this work who are not Palestinian is the part of the story where we say something about who we are. We are doing as good of a job at communicating solidarity as I’ve ever seen –– and we have to keep doing that –– but one thing I’m thinking a lot about lately is the necessity of empowering our movements to have the courage to fight from a place of collective self-interest. We cannot afford for our government to think Gaza only matters to people with relatives in the region, our government’s international policy and spending priorities impact all of us.

Another thing I think we deeply need modeled are alternatives to the story that the two sides of this movement are pro-Palestine vs. pro-Israel. This is a narrative that the media fuels that has contributed to the incredibly polarized moment we are in, and inhibited the growth of the movements that say: I’m pro-humanity. I’m anti-massacring children. I’m against fascistic operators playing their own people for sinister interests. We know these are incredibly widespread sentiments, but our movements have a lot of work to do to communicate this logic to the public. The conditions we’re in are so polarized that even offering that we could shift our framing makes me worry that I will be perceived as somehow endorsing the violence being enacted in my people’s name. I’m not.

Josh: I think that’s an important point. Palestine vs. Israel isn’t a frame that centers the occupation or the genocide when non-Arabs use it. It doesn’t leave room for defunded schools in America to protest destroying schools in Gaza. Or Israeli neonatal nurses to protest against the starvation of Palestinian babies. It promotes a false narrative that Palestinian happiness costs something.

The Forge: What are the most complicated and difficult narratives you’re working with right now?

Josh: It’s been very difficult to challenge the narrative that “Palestinian freedom endangers Israelis” without inadvertently perpetuating it. A lot of the negative press coverage of demonstrations doesn’t even bother denying the atrocities because just keeping it in a “Palestine vs. Israel” frame is so effective.

Unfortunately, and I want to say this with love because the fault is with our opponents, I think a lot of supporters are so used to being forced to speak in a Palestine vs. Israel frame that we’re missing the few opportunities we get to switch to a narrative frame that Palestinian freedom is everyone’s freedom.

We’re struggling to talk about how military spending is bad for every town and city in America, and that’s starting to hurt our ability to organize across historic divides of race and class. I’m repeatedly sitting in the back of meetings where Black organizers are saying the thing they need to get their communities behind Palestinian organizing is to connect it to reparations and reinvesting that war money into underfunded communities. There’s no sustainable narrative victory that doesn’t include talking about how we’re cutting school budgets and closing hospitals at home to bomb schools and hospitals in Gaza.

Rachel: I’d agree with Josh that this is the primary challenge, but I also want to talk about what makes narratives complicated. Generally as a society, I think we label things as “complicated” when they’re too layered with trauma and grief for us to deal with. It gives us an “out” not to face our own overwhelm. So when I think about overcoming difficult narratives, I think about changing the way that we hold trauma and grief and how visual practices play a role. The part of my own work that addresses this challenge most directly is a project called Vent Diagrams that I run with restorative justice educator E.M. Eisen-Markowitz. We’re both Jewish, and In the past year we’ve been working with Jewish organizers to make vents that support Jews in the complexities we need to move through in these times in order to stay in motion in solidarity with Palestine.

In the context of the United States, the complexities that Jews hold are unique because of the ways the U.S. government uses our ancestor’s traumas as a pawn in its military policy. But I think there’s lessons in it for all of us. Zionism is an adaptation of the idea that a nation state is a form of safety, and you don’t have to look very far back into Jewish history to find other, better ideas. I was brought into organizing by radical diasporists who taught me that one of the amazing things about Jewish culture is that, as a people, we pre-date the very idea of the nation state. Since the conception of Zionism there has also been another idea, Doiykayt or “hereness,” which states that our job is to build “Zion” or utopia wherever you live, with the people you live there with. And working with your neighbors to make the world better, that’s what keeps you safe. So the alternative to supporting the far right wing agenda currently governing Israel and terrorizing Palestine is to invest in our own people right here in the US and across global diasporas.

Here’s where it comes back to arts and culture: A central reason I believe my people are so confused about Jewish safety is that the israeli state and its supporters have invested in culture and used food, song, language, and art to sell global Jewish diasporas on the idea that belonging to a nation state could protect us and heal us from the traumas of the unspeakable violence enacted upon Jews –– not just the holocaust but also the Farhud and many other pogroms. The cultural building blocks of my ancestors –– icons, colors, songs, etc. –– could be used in the service of promoting internationalism. But instead they have been co-opted by warmongerers who use nationalist cultural production as a means to reinforce the Islamaphobic and racist impulses that Jews have learned from white Christian hegemony. It can be hard to imagine anything else because Israel has provided a place for Jewish refugees to go. Nationalism so boxes in our imagination that Jews and many others in the US experience the call for Palestinian liberation as a threat to anyone’s safety, as opposed to a reminder that the safety and liberation of all people are intertwined.