Emily Gallagher has been active in her neighborhood in Greenpoint since she moved there nearly 15 years ago. She’s organized for more parks and bike lanes, challenged luxury developers, and fought to preserve rent stabilized housing. Now, she’s running to represent her district in the New York State Assembly, taking on an incumbent who hasn’t faced a competitive primary since 1973. The Forge sat down with Gallagher and her campaign manager, Andrew Epstein, to talk about their upstart campaign and how they’ve pivoted their strategy during COVID-19.

This interview was recorded before the uprisings to defund the police. It has been edited and condensed for clarity and brevity.

Let’s start by talking about your political biographies: past organizing experiences, how you became politicized, and, ultimately, what led you to this campaign.

EG: I became interested in [radical] politics in college. It was the era of Bush Two. But I really wasn’t interested in [electoral] politics for most of my early twenties because I didn’t trust the people who I knew were involved in local politics. I thought that it seemed very careerist and not necessarily connected to social justice. I focused more on neighborhood organizing, especially around environmental justice and housing. And the more I did that here in Brooklyn — I started as soon as I got here, which was 2006 — I started to see what a difference it made if we had someone who was willing to stick their neck out in office or not.

I never thought about running for office myself until I was asked. I was part of a reform club called the New Kings Democrats. I joined that [organization] begrudgingly because I was an activist and I was like, “I am not doing that.” But then I started to see the intersection. In 2016, they asked me to run for District Leader, which is a position that most people don’t know exists [but] which, in the New York State Democratic Party, helps to determine who makes the backroom decisions about what the Democratic Party is going to do. And a lot of those positions are patronage positions. I ran against the patronage candidate who had had the position for 30 years. I really started to see that the head of the hydra of all of these problems was at the state level and the chambers of power there. I lost by just a few hundred votes. But I realized that, if we want to make change, we have to replace the people at the top with people who are reformers.

AE: I became politicized around 9/11, and, really, then the Iraq war. I was in high school, living right outside New York City. I went to my first anti-war demonstrations in 2003. I very quickly came to [feel] disappointment, both [at] the inability of the protest movement to stop the Iraq war and our inability to defeat Bush a year later. I spent much of college very involved in anarchistic-adjacent community organizing. The whole world of Food Not Bombs and publishing zines and all of that stuff. And while I have lifelong friendships and comradeships from that time in my life, I also think that we weren’t thinking terribly strategically about political change. And it wasn’t really until right after college when I started working with a local community organizing group in Binghamton that I got into very local level electoral organizing.

A major shift happened in my politics [when I went to graduate school] in New Haven because while I [had] intellectually and politically understood and supported the labor movement, I did not know, until I got to New Haven and was involved in UNITE HERE, what it actually took to work with people to discover their own individual and collective power to change their lives around [in order] to change the world. I realized politics was a lot harder than I thought [and] a lot more necessary than I thought.

After I left academia, I worked in nonprofit jobs for a couple of years. I got back into [political work] in the context of the real surge in left-wing electoral organizing in New York in 2018, volunteering on Julia Salazar’s campaign and Cynthia Nixon’s and AOC’s. When those victories really started to deliver, I realized I wanted to do this as a full-time occupation. It was my great fortune to have met Emily in September because it was immediately clear to me that she was the real deal. She had done the work in the community. She was known there. She’d been there for many years. It’s rare to find somebody who’s really dug in, in one place for many, many years and done the hard work that has led them finally to this point where they’re going to take this leap to political power.

Andrew, how did you bring what you learned from union organizing in New Haven into local electoral organizing work?

AE: The fundamental lesson I learned in UNITE HERE in New Haven was that politics is not just what you believe, it’s what you do. And the way the political and collective changes is through ever radiating forms of relationships. Deep trust, which is a hard one, so that you can push each other, hold each other accountable to deliver on the change that you say you want to make in the world. Coming to New Haven and being involved in the labor movement there made it clear to me on a much deeper level that we all need to hold each other accountable, build deep relationships. And that it takes a lot of hard work.

There’s a certain intensity in the labor organizing world, particularly the one that has delivered so much in New Haven, that I probably have brought to this campaign — a sense that we have finite days on this Earth and we must make use of each one. You have to make plans and you have to hold each other accountable. Especially when you have a lot of economic or racial privilege or some stability in your life, it’s so easy to float back into the easy choices, and that’s just not going to deliver the world we need.

Emily, what lessons did you learn from your campaign for District Leader?

EG: What I really learned is [that it’s] a lot harder — there’s a lot more strategy and making concrete choices and sticking with them that you need to do — when you’re doing a campaign. And you have these windows of time that you get to do certain tasks and you have to really make hay while the sun shines. You need to know in advance who is on your side and who you can tap for what, and you’re not going to tap the same people for everything. I think that it was really vital for me to rethink how I was going to create my team and not just take what was given to me, but actually seek out the right people that shared the conviction that I hold.

You decided to run in 2018. There’s been a lot of changes in the political environment over that time. How has the changing political world — from Bernie’s loss to COVID-19 — reshaped your priorities?

EG: I’ve never had very much faith or interest in federal-level politics. I think we can do a lot of incredible work at the local level so that’s always been my main interest. I’m pretty jaded about the federal level and I never really expect the movement to start there. We haven’t built the sufficient canopy for that kind of tree to grow. We need to have really strong local grassroots [organizing]. I’ve always been trying to get people to look at the local level. I think it’s actually a little easier to do that now that we’ve had COVID. People are starting to understand what the function of the federal government is versus the state government versus the local government in a way that I don’t think has been very tangible before.

AE: When you’ve been as engaged and embedded in local organizing and politics for as long as Emily has, you know the characters, you know the players, you know the institutional mechanisms and levers. And sometimes, you can be less in touch with the fact that there’s this vast majority in the districts that — forget not knowing what’s happening at Community Board One or not knowing the name of their Assembly member — they don’t know that there’s an Assembly. They don’t know that there’s a State Senate. Many people who are progressives and care about their neighborhood, for whatever reason, that’s just not where their head is at.

That leads into the presidential question. When we launched this campaign in September, I think Elizabeth Warren was the front runner. Bernie was being propelled by a left organizing faction. So it was always clear to me, even when Elizabeth Warren was the front runner, that Bernie was not going anywhere. And I think that I was hoping that those presidential level campaigns, particularly Bernie and Warren, would engage that mass in politics that we would be able to tap into and mobilize. We were not going to have the reach of the Bernie or Warren campaigns, but we were going to go after so many of the same voters. So through that fall, when Warren was the front runner — and I remember vividly when Bernie had a heart attack. I was in the district. I remember sitting on a bench and weeping in McCarren park. I thought that was really the end of that. I was quite scared at that point. But then, of course, the resurgence of the Bernie campaign, and there was a sense that we were going to be heading into, at the very least, a highly competitive and politicized presidential primary in April. Everybody would be engaged in politics. We were going to mobilize off that.

And then, one by one, the Democratic Party establishment — with incredible speed and force — consolidated around a historically weak nominee and then a global pandemic happened, which shut down everything else. All of the door-to-door, everything that we had planned as being the thrust of our organizing efforts in this campaign, was upended. Both of those things. Mobilize off of Bernie and Warren, do the door-to-door work that it takes to win — gone.

How have you pivoted?

AE: I don’t know about you, Emily, but I felt like those first two weeks after the shutdown in New York, I was gobsmacked. I didn’t want to say that this was it, but my assumption was, we were not going to be able to raise any more money. We were not going to be able to do a whole lot. We were going to get through the campaign somehow. But my life as a paid staff around this campaign was probably going to be over. We were going to put in a respectable effort while maintaining all of the social distancing guidelines, focus on what we could do to help people out and just hope something worked.But, after those first two weeks, I think people were recognizing how central democracy, democratic engagement, and political organizing are to surviving this. And, after those first couple of weeks, we found a way to really pivot.

EG: We have a lot of interplay with other candidates who are running. We’re sharing ideas and brainstorming together. It was a collective effort for all of the challenger candidates to figure out: How are we going to tap into the electorate now that we can’t do the main thing that we were going to do? And how are we going to reach the people who aren’t on social media? How are we going to make the most use of our money, which we know is going to dwindle? How are we going to raise more money? How do we do that in a way that’s appropriate and respectful?

AE: We have a lot of deep and organic connections, too, to the people who sprung into action around mutual aid efforts and [we] have been supporting those, plugging people into them. When we got back up and running the phone banking, it was all: Check in. It was, are you okay? Do you need food? Do you need medical care? Are you handling the rent situation? All of that. And again, being so connected with the mutual aid movement, it was very easy to redirect people into that effort.

Let’s talk a little bit about the tactical shifts you’ve had to make. What did your volunteer structure look like before and how have you reshaped since COVID?

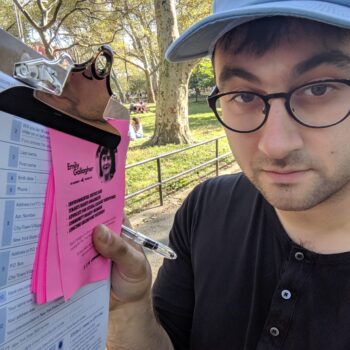

AE: There’s this period of time in New York called petitioning where you have to get a certain number of registered Democrats to sign your petition to get on the ballot. And we were going to use that time as the big launch of our field operation. March 1st start, don’t stop till June 23rd, three, four canvases a week. And there’s a photo I can send you, which in retrospect is vaguely horrifying because we know COVID-19 was very much in circulation on March 1st in New York City, and the failure of the state and local government to adequately tell people is another story. But we did this field launch on March 1st, tons of people. There were probably 30, 40 people, and we were like, “This is the beginning.” And that was the vision. That’s how you win local elections. You knock on a fuck ton of doors over and over again. Especially now because people really don’t like to pick up their phone anymore.

The switch to phone banking, we’re going at that hard. It has a pretty low success rate in terms of people picking up and engaging. But the conversations you do have are quality and important. There’s a lot of great political tech now. There’s this app called Reach that came out of the AOC campaign, which is a really easy-to-use interface on your phone to identify voters, to talk to them through text. That’s been really useful. Text banking. The stuff that comes out of campaigns that prioritize organizing is the stuff that really works. Like the people who did AOC’s digital operation built an app. Well, that’s the one we used because that was really successful. The people in the Bernie campaign built a system for text banking. That’s what we’re using, and there’s a lot more like that. Do we wish we could be having conversations on the door? Absolutely. But luckily we’re at a moment when there’s a lot of ways to reach people.

How have you been able to maintain or grow volunteer engagement?

EG: We are blessed with a pretty devoted core crew of about 25 to 30 people [for whom] this has become part of their identity and their social life. We’ve been using Slack to organize that. And I think that’s been a nice way to bring people in and give people an opportunity to start getting their feet wet. We’ve got a core group of moms, of people whose kids are also volunteering on the campaign — and Andrew’s mom — who are really engaged. One of my activist friend’s moms is really engaged. So I think we’ve been able to actually make volunteering a little more accessible for some people.

One of the things that I love about being on campaigns is the sense of community you build with people. It seems like that, on the one hand, makes the campaign a potentially important space right now. But I’m assuming it’s also something that’s challenging to maintain or build out because we’re not actually with each other. How are you thinking about that community-building work right now?

EG: Finding the ways that people are going to engage best and letting people use their talents is how you get folks cemented in. I have a friend who’s a musician, he’s working on a fundraiser for us. Making sure that you’re creative and open. Making sure that people are feeling seen and heard and respected, and that they’re not just there as a mercenary in a role that anybody could fill. That it feels like it’s their role and that they’re choosing to participate in that role is really important. We used to just give out the phone bank info and have people call, but then we started doing it with Zoom and everybody’s in a Zoom room so that people can see each other and still feel like they’re together. And then we have a warmup where we’re all chatting and we meet in the middle and then we meet at the end to talk about any funny situations that happened or achievements or things they want to troubleshoot. Really making sure that you’re creating spaces for people to actually connect so it’s not all solo work.