Since the election of Trump in 2016, and even more acutely since George Floyd’s murder and the subsequent uprisings during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, organizers have faced an increasing number of polarized internal conflicts in our organizations. Maurice Mitchell described these conflicts in “Building Resilient Organizations” in 2022, identifying and analyzing many of the factors contributing to them. But even as an organizer and coach well-versed in these conflicts, I found myself surprised at how fast things escalated with a conflict of this type in my organization. As a virtual organization we didn’t have to see each other in person, and I was left wondering what might have happened if we’d been in an office. Would our communication have missed each other so much if we’d been face-to-face?

When I knocked on doors for my first time, in 2006, I used a clipboard and pen, paper flyers, and a flip phone in my pocket. Today, we might do that same kind of outreach over social media and Zoom, or it might at least use a digital device rather than paper and pen. This change is a process called “mediatization,” and it undeniably has impacted how we organize in many, many ways.

Mediatization: the process by which our daily practices, social relationships, institutions, society, and culture are impacted by an ever-increasing dominance of the role of the media, through mediated communication and technological practices (Figueiras, 2017; Hjarvard, 2013; Livingstone, 2009).

We sometimes talk about the role of social media callouts and Slack channels and Zoom meetings in the conflicts our organizations are facing. But – with Artificial Intelligence continuing to gain a hold in workplaces, I want to ask us as organizers to ask a broader question about mediatization. I want to invite us to really reflect on how mediatization is impacting our organizing, our relationships, and contributing to our internal organizational conflicts. While I believe that embracing new technology can both improve our organizing and increase our efficiency, I also want us to pay attention to when we need to get back to the basics, pick up the phone, or meet face-to-face.

This piece is the result of an academic research project, where I interviewed organizers and some of the coaches and consultants that we call in to help solve our conflicts about mediatization and conflicts. I’m choosing to share it in this format, for organizers, in hopes to spark conversations about mediatization in our organizing. I’ll give a broad description of mediatization and how it impacts organizing, then dive into how it impacts organizational conflicts, and finally discuss some ideas of where we go from here.

What Is Mediatization and How Is it Impacting Organizing?

If we translate the above definition of mediatization into terms that are useful for organizers, mediatization is a process by which our recruitment, turnout, meetings, actions, relationships, organizations, chapters, committees, coalitions, neighborhoods, cities, states, and our cultures are changed by how we use technology, especially in our communication. Technology is impacting how we organize in every part of our work.

Mediatization is happening, whether we like it or not. Media and technology are everywhere, built into every aspect of our lives, and cannot be avoided. Whether you are the kind of organizer excited to embrace the next new action platform, or you are the last holdout on your team with a paper call list, the mere fact we must choose these methods shows how ubiquitous mediatization is. In other words, it isn’t just about the change in what medium we’re using, it is about how that change changes everything, from how we think, to what tactics we can employ, to how we can bring people together, and more.

To really understand the full impact of mediatization, we can break it down into four parts: extension, substitution, amalgamation, and accommodation. Each of these are impacting how we organize:

-

Extension refers to using technology to surpass our human limits of time and space. Mediatization has extended what we can do, and in organizing it’s created a bunch of new efficiencies: often things we take for granted like using a map on a smartphone to navigate to our house visits. It’s hugely impacted how we do recruitment, where instead of cold calls, “… now you’ve got a whole set of leads that have gone through some type of interaction before they get to an organizer.”

-

Substitution is the process where we partly or completely substitute social activities or institutions, and it is a process that has opened new horizons of tactical possibilities in organizing. From massive tele-townhalls, email lists fundraising, and base building through social media, mediatization has created new possibilities for organizing and campaigning, changing how organizers think about their work. Substitution gives new options of how we can wield power.

-

Accommodation is about how we must change to adapt to the changes of mediatization. For example, the number of communications channels we use to talk to each other has expanded, requiring us to choose which channel to use. One organizer recounted how calling a supervisee might lead them to say, “’I didn’t realize it was an emergency!’” even if it was just a phone call to check in. Accommodation also includes ways that organizers have to learn to think about storytelling differently, which can lead to new possibilities. One organizer cited an example of housekeepers taking selfies with thermometers on a hot day to share on social media in real time, tagging the bosses. It’s the same story we might tell in a delegation visit, but a new method of how and when we think about telling that story. Accommodation is all about the ways we must change our thinking in a mediatized world.

-

Amalgamation is how media becomes a part of the space of our everyday lives. Many public actions now include live-streams or other live media posting, amalgamating media creation and publishing with the activities of taking action. In other areas of day to day organizing, amalgamation can be seen in ways that media tools become a part of the routine, such as the replacement of clipboards with tablets or smartphones.

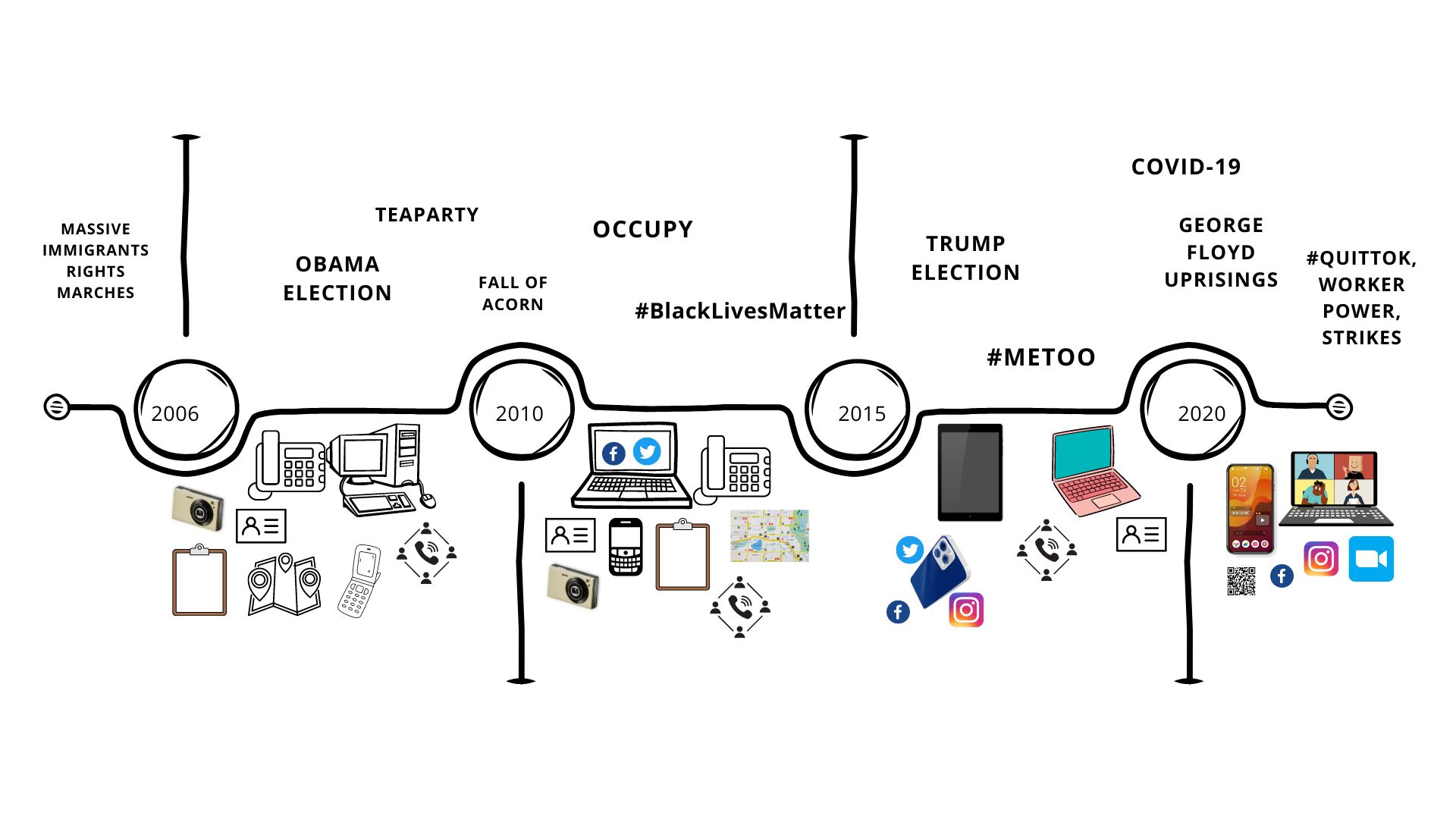

Through interviews with veteran organizers and my own experiences, I created a timeline of how mediatization has impacted organizing over the past 20 years (or so). Click here to see a visual and a detailed text version of this timeline. Mediatization is transforming organizing in an ongoing fashion, whether we realize it or not.

Mediatization’s Role in Organizational Conflicts

Mediatization has impacted organizing, but how might it be contributing to organizational conflicts? I interviewed three coaches/consultants who have worked with many organizations in crisis to identify patterns, Erin Trent-Johnson, Ja Young Ahn-Williams, and Rebecca Epstein. (The organizations they work(ed) with are kept confidential.) I’m proposing that mediatization is impacting organizational conflicts in three ways: Extended Anxieties, The Disembodied Voice of Remote Work, and the Power of Social Media Call-Outs.

Extended Anxieties

In 1964, a communications theorist named Marshall McLuhan wrote about the psychological impact of technology’s extension of our human capacities:

“When our central nervous system is technologically extended to involve us in the whole of mankind and to incorporate the whole of mankind in us, we necessarily participate, in depth, in the consequences of our every action.”

He called it an “Age of Anxiety” where people can no longer ignore those with whom they are not in physical contact. And that was in 1964, long before the internet, smart phones, or social media.

Drawing on his description, I am calling the way that mediatization contributes to the generalized anxiety and stress that ripen the conditions for organizational conflict Extended Anxieties. Maurice Mitchell begins his description of the roots of these organizational conflicts by describing the multiple overlapping crises of this moment: “a global pandemic, rising authoritarianism, climate emergency, political violence, unprecedented economic inequality, and general precarity.” Epstein described the uprisings responding to the murder of George Floyd as the moment when she noted a significant increase in organizational conflicts. But even before those events, she believed organizers were facing increased stresses that were:

“compounded by the multiple layers of pandemic, remote work, isolation, fear, different degrees of trauma at an individual level, combined with ridiculous pressures that people were feeling and experiencing like having to take care of children and work, and or being all alone.”

It is important to note that some of the anxieties people were experiencing were from direct lived experience. But mediatization extended the information people accessed while in pandemic isolation, ripening conditions for increased conflicts.

As we are currently witnessing a mediatized genocide and as the 2024 election cycle ramps up, along with all the other atrocities we can access just by picking up our phones, this Extended Anxiety continues in our lives and continues in our organizations.

The Disembodied Voice of Remote Work

As pandemic lock-downs began in 2020, community organizations rapidly shifted into a context of remote work. This transition required a “reconfiguration of life” as family members needed to figure out how to behave in new patterns now that work and school were being done through media in the home, in a new amalgamation of media and non-media life.

While it impacted our home lives, it also impacted our work lives. Working alone at home, and often doing tasks in new ways, created a more difficult work environment, and simultaneously remote work made it harder for supervisors to provide support and accountability. For example, sending an email allows more control of both what is communicated and the response, as compared to a face-to-face conversation where there’s more possibility for broader conversation. As a larger variety of communication channels emerged, such as Slack, Signal groups, and G-chat, each had different levels of officialness/informality and ways of being used, where informality can be helpful for working out complex problems. Yet, as Ahn-Williams observed, “The way things moved …[was] so much faster because there were so many other ways to communicate with each other.” Communication accelerated and sometimes lost nuance or informality.

“The virtual environment (zoom meetings) may be convenient for all kinds of reasons, but it’s a pretty lousy medium once there’s conflict in an organization,” said Jonathan Smucker in an interview on organizational conflicts for the Intercept. Adding to this description, Epstein said, “When they can just be a voice –– like literally a disembodied presence –– it’s almost impossible to connect with someone.” As organizations use new or more mediatized communication methods it impacts the communication itself, including on how participants feel connection, and sometimes contributing to the “cycle of disconnection” that “drives ‘us versus them’ dynamics, exacerbates mistrust, and grinds work to a halt.”

The title of this piece, “just pick up the phone and call,” is an invitation to a response to this pattern. As one organizer commented, while messaging each other some of the meaning might get lost, but “In person, or with the nuance of a phone call… you’re simultaneously hearing each other’s expressions,” and that calling someone up might be a “superpower” in our current context.

The Power of Social Media Call-Outs

Call-outs on social media, where activists use social media to air grievances in public, often watering down more complex conflicts to attack a leader’s character, have impacted these conflicts. Mitchell wrote, “These platforms — owned and controlled by megacorporations — reward us for our ability to articulate or reshare the sharpest, pithiest, pettiest, most polemic, or most engaging ‘content.’ There is no premium on nuance, accuracy, and context.” We can see this pattern as part of the impact of accommodation –– we shift how we communicate because of how the medium works.

All of my interviewees agreed that the murder of George Floyd was a pivotal moment: organizations who were dedicated to social justice felt pressure to make a bold public statement, usually over social media, and, as Ahn-Williams commented, if the organization had not cared about these issues before, then the organization needed to “stand on it, ‘cause if not your entire staff’s gonna’ come for you.” She commented on how not only was the official statement important, but personal social media statements, or lack thereof, were important due to “everyone’s surveillance of each other.” The fear of being next to be called out fuels a culture where leaders feel that they must take a stand online. As adrienne marie brown wrote:

“Many of us seem to worry … that we will be next to be called out … or just disposed of for refusing to group-think and then group-act. Online, we perform solidarity for strangers rather than engaging in hard conversations with comrades.”

Leaders often feel the need to be extremely cautious, as one organizer I interviewed described:

“Whatever written document or complaint or set of things that have been discussed by what might be a lot of people, or even a few people, has potentially a lot of power for good or ill online, but it may very quickly go to an audience that does not have any relationship or a lot of context who respond to it based on their own experiences. Which means management that needs to be pretty careful and legally prescribed and how they respond in writing, but also even verbally.”

Not only are the words important, but the body conveying the message matters. Trent-Johnson noted the importance of “the modes and codes” of communication and how many organizations instrumentalized Black and other women of color’s bodies to be part of their communication and statements.

Call-outs are wielding power and causing leaders and organizations to change their behavior. As organizers, we need to ask ourselves if our working definitions of power adequately account for this impact. Many of us were trained that:

Power = Organized People + Organized Money

But this definition doesn’t adequately account for the full impacts of social media call-outs. Some organizations are now naming “narrative power,” which we might conceive of in relationship to Manuel Castell’s definition of (hegemonic) power, exerted through either domination or controlling of discourses through communications, as “the relational capacity that enables a social actor to influence asymmetrically the decisions of other social actor(s) in ways that favor the empowered actor’s will, interests, and values.” We might change our definition to include the power that comes from influencing narratives, beliefs, and stories, perhaps something like this:

Power = Organized People + Organized Money + Narrative Influence

Where do we go from here?

As new technologies like AI expand their reach, mediatization will continue to impact our work as organizers. The impacts of mediatization are not all good or bad: while I argue mediatization has contributed to organizational conflicts, it has also created new efficiencies, tactical possibilities, and allowed us new ways of thinking. So where do we go from here?

First, I want to invite organizers to learn the word mediatization and to add it to our collective vocabulary. In order to understand the moment we are organizing in, to develop our campaigns with intentional choices about when to use –– and when to not use –– new media, and to understand how the various impacts of mediatization are changing our organizations, having a working understanding of mediatization is an important tool to add to our toolboxes. Part of this work is developing media literacy trainings within our organizations to both develop our skills using new tools, but to also understand the risks and range of impacts that they have. Increasing our understanding of mediatization (and related topics like post-truth, surveillance capitalism, and social media bubbles) can increase our capacity for quality communication with each other, with our base, and in our campaigns. We can improve our capacities to embrace new options and to discern when to cut through the noise and go back to the basics with good old-fashioned house visits.

Next, we need a working definition of power that can account for media and narrative, but without losing sight of the power of organized people or organized money. This is a conversation that is already happening, with various groups talking about “narrative power” or sometimes “cultural power” and lots of groups creating social media campaign strategies. But because the definition of power is so essential to organizing, we need to make sure that we aren’t just having conversations in the pursuit of foundation money, where we want to perform our innovativeness rather than share where we’re questioning what we believe. We need to have these conversations in practice, with each other as we run campaigns, such that we can try out our working hypotheses and continue to refine.

And finally, we need to bring our awareness of mediatization to how we run our organizations. As we use the framework laid out in Building Resilient Organizations, I want to encourage us to be aware of the places where mediatization furthers stresses and increases risks. More than ever before our mistakes can be captured, held on to, and broadcast out while we simultaneously absorb as much violence and terror as we allow onto our screens. Neither ignoring injustice nor avoiding taking risks feels like an acceptable option to most organizers, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t stress us out. So, as we think about strengthening our organizations, let’s use our understanding of mediatization to think about how we can, and how we can’t adjust for the world we’re living in throughout our organizations.