Originally Published in Waging Nonviolence

This spring, student encampments protesting Israel’s war on Gaza spread across colleges throughout the United States, resulting in campus lockdowns, occupied administrative buildings, canceled graduation ceremonies and scores of arrests. But even before this latest wave of action, we have witnessed in recent years a proliferation of disruptive protest, spanning a wide range of social movements.

A small sampling of activity since the start of 2023 could note that animal rights advocates have disrupted the UK’s Grand National horse race and Victoria Beckham’s fashion show; abortion rights protesters have been sentenced for impeding the proceedings of the U.S. Supreme Court; striking dockworkers “upended operations at two of Canada’s three busiest ports;” and climate protesters have blocked access to oil and gas terminals, chained themselves to aircraft gangways to prevent private jet sales, and spoken out forcefully at corporate shareholders meetings.

Given the urgency of the challenges in our world, this wave of disobedient and determined action should generally be regarded as a positive development. Because it breaks the rhythms of orderly business in society, forcing both the public and those in positions of power to pay attention to issues of great importance that might otherwise be downplayed or ignored, disruption is a vital tool of civil resistance.

However, not all disruptive protests are created equal — and not all are equally beneficial in advancing a cause. Some actions can win popular support and lead to a snowball of escalating energy within a movement. Others can drive away potential participants, repel sympathizers and invite state repression. Put another way, some actions lead to victory, while others trap activists into a cycle of self-isolation and alienation from the wider public.

To be clear, in the face of injustice, action is preferable to silence. At the same time, studying the dynamics of polarization can help movement participants maximize their impact and prevent occasions when protests backfire.

But before they can work on the skills needed to harness the power of polarizing action, organizers must engage with more basic questions: Why is polarization around specific issues even necessary? And how can movements know when they are using it effectively

Understanding how protests polarize

The idea of an issue being polarized is most commonly talked about in negative terms. But to the extent that polarization around an issue is not present at a given time, it is not because difficult underlying tensions do not exist, but rather because politicians sweep them under the rug. They avoid them for fear of generating controversy that could fracture the political coalitions that keep them in power. In an interview discussing his 2020 book, “Why We’re Polarized,” author and New York Times columnist Ezra Klein explained “the alternative to polarization in political systems often isn’t agreement or compromise or civility — it’s suppression. It’s suppression of the things the political system doesn’t want to face[.]”

Protest actions are polarizing. This means that they force people to take sides on an issue. And, contrary to what some may think, that is not a bad thing when it is used for progressive ends.

To take just one example, the civil rights movement was certainly polarizing. But were we really better off living with widespread and often bipartisan acceptance of Jim Crow segregation and the racist terror used to enforce it? Likewise, defying prevalent homophobia and affording equal marriage rights for LGBTQ couples involved considerable controversy and required politicians to take stands that most had long preferred to avoid — until social movements forced them to change course.

Polarizing protest takes a suppressed and simmering issue and brings it to a boil, moving it to the fore of public discussion and, at least temporarily, placing its consideration above other disputes and ordinary deliberations. As famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass contended, earnest struggle for progress is “exciting, agitating, all-absorbing, and for the time being, [puts] all other tumults to silence. It must do this or it does nothing.”

The polarization of an issue, in this respect, is both an inevitable and necessary part of the process of social change. In the words of sociologist Frances Fox Piven, a preeminent theorist of disruptive power, “[A]ll of our past experience argues that the mobilization of collective defiance and the disruption it causes have always been essential to the preservation of democracy.”

The point here is not that polarization is good in itself. In the wrong hands, it can do great harm. For example, conservatives can generate polarization in ways that set back social justice — like when they employ racist and xenophobic tropes to effectively turn up public anger against immigrants. But it is essential for progressive movements to recognize that polarization is a force they can use as a tool, rather than something that simply must be avoided.

Yet even once organizers grow comfortable with the idea that their actions will be polarizing, crucial unanswered questions linger. Making people take sides on an issue is one thing. Making sure they take your side — crafting protests that compel members of the public to sympathize with and support a group’s cause, rather than driving them into the arms of the disapproving opposition — is another. So how, then, can movements do that?

Too often, observers and participants alike consider the success or failure of protests to be mostly a matter of luck, resulting just from historical conditions. Or, they look at protests only through a moral lens, at which point the imperative to just “do something” or “speak truth to power” replaces hard-headed analysis of the impact of one’s actions. Yet those who wish to act more strategically can find a large and growing pool of resources to help.

Social movement theorists and scholars of disruptive power, Piven prominent among them, have analyzed how groups who may possess few conventional resources and enjoy little influence in mainstream politics can nevertheless leverage change through withdrawal of cooperation in status quo systems. An entire field of “civil resistance” has emerged in recent decades that employs both careful study of historical cases and practical experimentation in dissent to discern key principles that can be used by organizers. Still others have focused on developing theories of narrative change and story-based strategy, providing insights and best practices related to the communicative properties of protests.

From radical flanks to a Birmingham jail

The combined message of this varied collection of thinkers is that there is a method to the apparent madness of collective mobilization. Both through examining this scholarship and drawing from the wealth of lived experience passed forward by on-the-ground activists, interested practitioners can learn a lot about what tends to work when it comes to polarizing protest, what tends not to, and why.

But the truth is, it’s complicated.

A safe rule of thumb for protesters is that, if they are acting nonviolently in pursuit of a just goal, taking a stand is far better than passivity or complacency. At the same time, in managing polarization, there is always room for organizers to improve their skills and refine their feel for shaping protest outcomes.

The dynamics of polarization remain complex for a variety of reasons. For one, polarization works differently in the context of a short-term electoral contest than in longer-term activist campaigns, the contours of which we are focusing on here. Second, the good and bad effects of controversial protest do not come as an either/or proposition. Instead, positive and negative polarization occur at the same time. Highly visible protests that draw in new sympathizers will simultaneously drive away other people who are turned off by activist tactics and demands. Thus, the White Citizens’ Councils grew in the South when the civil rights movement launched its most high-profile campaigns, such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Because organizers cannot avoid polarization, both good and bad, their goal must be to ensure that the positive results outweigh the negative. They must use good judgment as they engage in a cost-benefit analysis of any potential action.

One concept related to the positive and negative sides of polarization is what social movement theorists call the “radical flank effect.” The idea here is that sometimes the presence of a more militant faction within a movement — made of activists who deploy more controversial, outsider tactics — can make the demands of mainstream reformers appear more reasonable. Such radicals can advance the ability of insiders to extract concessions from people in power, who grow willing to negotiate with the “respectable” face of dissent when confronted with the threat of a more impolite and uncompromising alternative.

These outcomes are examples of positive flank effects. However, those who study radical flanks point out that the behavior of a militant fringe is a double-edged sword. Negative flank effects occur when extreme actions undertaken by a group on a movement’s margins—particularly actions that the public perceives as violent—end up inviting overwhelming backlash, discrediting the cause as a whole, and providing justification for the harsh repression of even modest dissent. Like with polarization more generally, the goal therefore must be to maximize positive flanks effects while minimizing negative ones. And once again, this requires rejecting an “anything goes” mentality and instead exercising both judgment and discipline.

Another reason that polarization is complicated is that protests prompt members of the public to polarize around several different things at the same time. Distinct responses can be measured with regard to how observers feel about the issue at hand, what they think about the methods used by those carrying out the action, and how they view the target of a protest. For example, it is possible that people will say that they dislike a protest, but that the action will nevertheless be successful in making them view the target of the actions less favorably.

Another very common result is that, when asked about a demonstration that makes news headlines, respondents will report sympathy for the protesters’ demands, but they will express distaste for the tactics deployed. They will see the activists themselves as too noisy, impatient, and discourteous. This is an age-old dynamic, and one addressed eloquently by Martin Luther King Jr. in his renowned 1963 “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” This letter was written not as a response to racist opponents of the movement, but rather to people who professed support for the cause while criticizing demonstrations as “untimely” and deriding direct action methods. “Frankly I have yet to engage in a direct action campaign that was ‘well timed’ in the view of those who have not suffered unduly from the disease of segregation,” King quipped. But confronting these criticisms, he made the case for why the movement’s campaigns were both necessary and effective.

For social movements, it is acceptable if mainstream observers dislike the disruption and tension caused by protest, so long as support for the underlying issue grows. When it comes to nonviolent resistance, this is the case more often than not, which is why the taking of collective action should be widely encouraged. That said, there are times when a movement’s chosen tactics are so controversial and despised that they overshadow any discussion of the cause itself. Therefore, with all actions, organizers must weigh the relative benefits of the polarization created against potential downsides. Organizers must use any and all means at their disposal to measure this response — whether formal polling data and focus groups, or simple conversations that pay attention to the responses from different groups of people, especially those outside their most immediate circles.

The spectrum of support

Overall, the goal of the movement is to shift the “spectrum of support” in its favor.

Many different organizing traditions have recognized that victory does not come from total conversion of all constituencies, but rather through making more qualified progress. In the labor movement it is common to place workers in a given shop on a one-to-five scale, based on their level of commitment to the union. “Ones” are strong leaders who will convince other co-workers to vote yes for the union. On the other side of the scale, “fives” are employees who are resolutely anti-union and actively side with the boss. Everyone else in the shop falls somewhere on the continuum between these extremes.

An organizer would not expect to win over everyone. But their job is to at least partially move those who can be persuaded, and to minimize the zeal and influence of those who cannot be swayed. The union must work diligently to make indifferent “threes” into more supportive “twos.” It must motivate existing “twos” to step up and become more active leaders. And, finally, it must aim to dampen the negative attitudes circulating among “fours,” convincing members of this group to abstain from actively supporting the opposition if they cannot be moved to defect entirely.

Coming from a different tradition, the spectrum of support — sometimes called the “spectrum of allies” and credited to Quaker organizer and activist trainer George Lakey — provides a visual representation of the same principle. The Momentum training community presents it this way:

For movements to win, they do not need to convince their worst enemies to change. Instead, they win by turning neutrals into passive supporters and turning passive sympathizers into active allies and movement participants. Meanwhile, they should aim to whittle away at ranks of the opposition — making them less resolute, active, and committed, even if these people never move beyond being neutral at best.

As 350.org puts it, the good news is that “in most social-change campaigns it is not necessary to win over the opponent to your point of view. It is only necessary to move the central pie wedges one step in your direction…. That means our goal is not to convince the fossil fuel industry to end themselves. Instead, it is moving the rest of the society to shut them down.”

In the diagram above, the arrow shows the direction in which organizers want people to move. In practice, however, they must accept that there will be some motion each way. In the wake of polarizing actions, it is not unusual for both the movement and the opposition to grow: opponents may be able to rally die-hards to their side who feel threatened by the issue at hand, as did the White Citizens’ Councils. Yet if, on the whole, organizers are moving greater numbers toward their side, they can count themselves as making headway.

In short, polarization is a multifaceted equation — and only by working hard to do the math can those who seek to use it get continually better at improving their results.

Against protest shaming

In recent years, there has been considerable research published which attempts to measure radical flank effects and track the polarizing effects of movements. While there are limits to how much protest impacts can be precisely quantified, the cumulative result of such research, in the words of one literature review, is to point to “strong evidence that protests or protest movements can be effective in achieving their desired outcomes,” and that they can produce “positive effects on public opinion, public discourse and voting behavior.” Both the historical experience of organizers and recent studies also provide backing for the idea that support for a movement’s issue can grow, even when a majority of people do not particularly like the tactics being used.

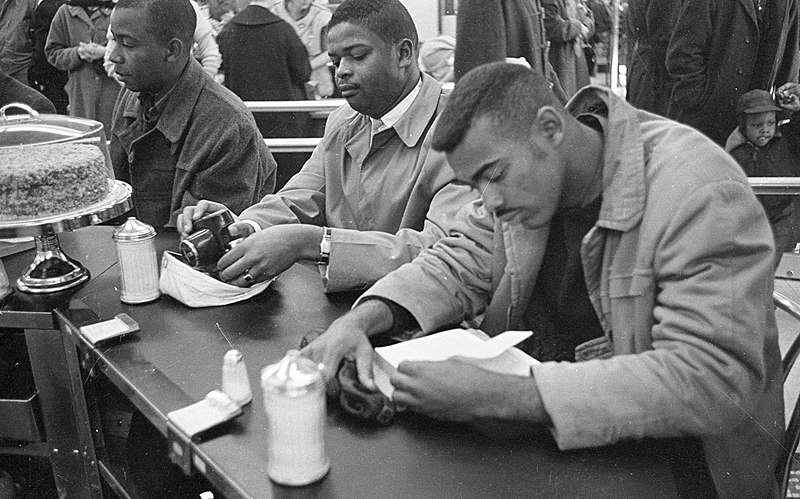

Nevertheless, with each new wave of protest, there is inevitably a rash of mainstream commentary about how protesters are naive and likely to harm their cause. Certainly this is the case with this spring’s pro-Palestinian student encampments, which elicited a raft of “protest shaming” articles claiming that the occupations were counterproductive. Often, those making such admonitions invoke an earlier age — such as the 1960s civil rights movement — when protest was ostensibly more dignified and effective. These overlook polls that showed how wide swaths of the public saw lunch counter sit-ins, “Freedom Rides” to desegregate buses, and even the March on Washington as being harmful to the winning of civil rights. Of course, all of these actions are now considered hallowed landmarks in the struggle for progress in the United States.

Because they appeal to public cynicism, which remains very widespread, about the ability of protests to make a difference at all, protest-shaming pundits can find fertile ground for their arguments. However, their perspective is rarely based on a hard evaluation of contemporary research or deep engagement with the history of social movements. Most often, it results in bad advice: Activists are told to work within establishment channels to pursue change, to avoid controversy, and to be more patient with the system — the same counsel King wrote of having received from erstwhile allies many decades ago.

Instead of conforming to critics’ preferences and seeking to avoid polarization altogether, movements do better to carefully study how they can use it to their advantage. Understanding that both positive and negative polarization occur at the same time means that protesters can win, even when there is backlash. Understanding that a movement’s cause may benefit, even when there is negative perception of the tactics deployed, offers a critical distinction in measuring success. And understanding the spectrum of support allows protesters to gauge when, on balance, they are advancing and when they need to reevaluate their actions.

Protest movements take a gamble when they unsettle the status quo. But it is a risk worth taking. For it is only when movements appreciate how polarization can be used as a tool that they are poised to make their greatest gains.