This interview is part of a series of articles from The Forge and New America spotlighting successful stories of co-governance models across rural, urban, and tribal communities.

Collaborative governance — or “co-governance” — offers a model for shifting power to ordinary people and re-building their trust in government. Co-governance models break down the boundaries between people inside and outside government, allowing community residents and elected officials to work together to design policy and share decision-making power. Cities around the world are experimenting with new forms of co-governance, from New York City’s participatory budgeting process to Paris’s adoption of a permanent Citizen Assembly. More than a one-off transaction or call for public input, successful models of co-governance empower everyday people to participate in the political process in an ongoing way. Co-governance has the potential to revitalize civic engagement, create more responsive and equitable structures for governing, and build channels for Black, brown, rural, and tribal communities to impact policy-making.

Still, co-governance models are not without challenges. The hierarchical and ineffective nature of our current governing structure is difficult to transform. Effective collaboration between communities and politicians requires building lasting relationships that overcome deep distrust in government. So far, successful models of co-governance tend to be local and community-specific — making it critical that we share stories of success and brainstorm ways to scale.

In this series, we share stories of co-governance in practice. For this interview, New America’s Hollie Russon Gilman and Lizbeth Lucero spoke with Richard Young, the executive director of CivicLex, an organization in Lexington, Kentucky that builds civic health through education, civic transformation, and relationship building. Here are edited excerpts from our conversation about Young’s vision for Lexington residents to meaningfully participate in the decisions that shape where they live.

Could you tell us about the work you’ve been doing at CivicLex and how you’ve engaged with local communities to build civic power?

New America’s work on co-governance is essentially our entire mission at CivicLex. Our organization brings community members into direct relationships with people in positions of political power in order to move our city towards a more participatory local democracy. Relationship building is central to what we do, and we have different types of work that blend into each other.

The first type is adult civic education, which is focused on helping residents understand how policy gets created. When people don’t understand the important issues that are going through city government, they are much less likely to be engaged. One of the ways we operate is essentially as a local news outlet, keeping people up to date on what’s happening inside City Hall, in committees, and at various levels of government. We conduct in-person educational workshops to help people understand everything from the budgeting process to local redistricting. All of these are done with a focus on relationship building and creativity to bring together local residents and people inside city government.

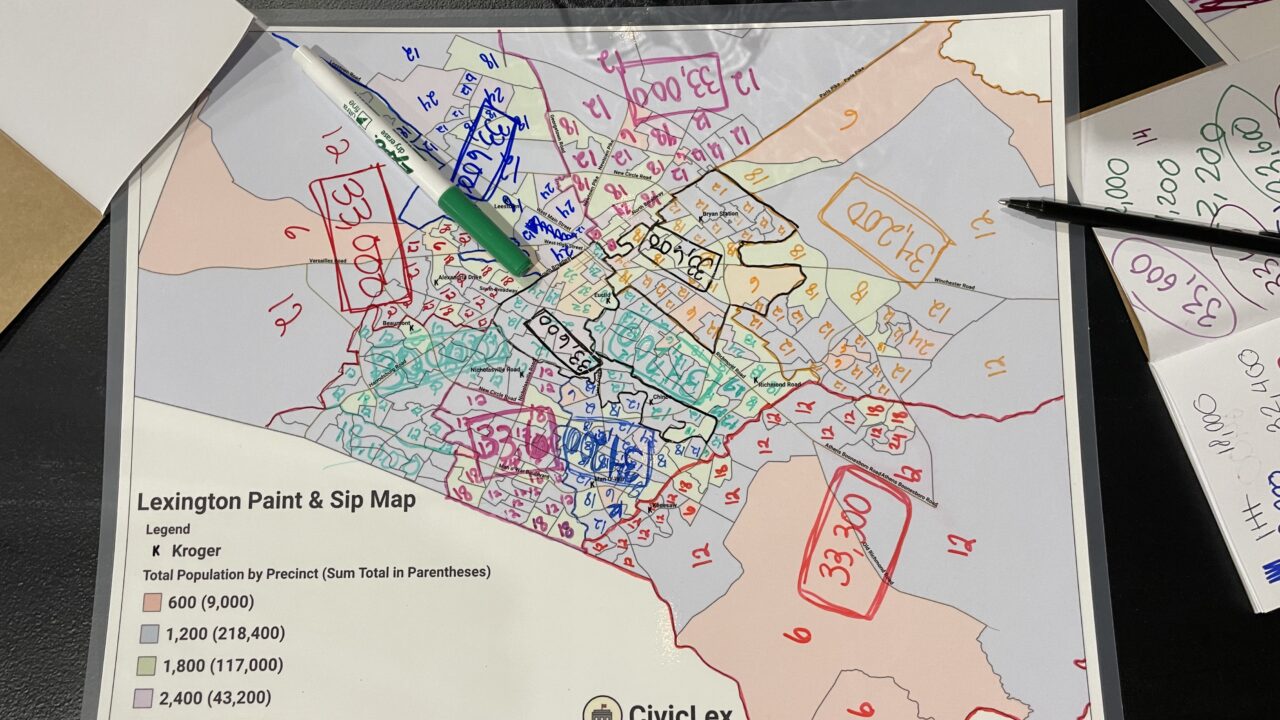

For example, we used a creative lens to conduct our redistricting work and hosted a redistricting paint-and-sip workshop at a local brewery. Residents were able to paint their own redistricting process while following the official redistricting rules. What’s really important is that the workshops also had members of the redistricting commission, GIS analysts, and people from different departments in city government who influence the redistricting process. They were not necessarily there to say, “This is how it’s done,” but to see and hear how people were reacting to the process, learn from people’s experiences, and use the workshop as an opportunity to make informed policy decisions.

We do the same thing with the city’s budgeting process, bringing people from the city’s revenue, finance, and budgeting departments together to help residents better understand the process and build human relationships. In a mid-size city like Lexington, we can start to build authentic relationships. And it’s vital, especially for people that are in marginalized communities, to have access to these relationships with decision-makers in a way that is typically not available to a lot of people.

Another type of work we do is civic transformation projects, which are focused on altering how our city government functions in order to make it more participatory. For example, we are working with our City Council to change its formal meeting structure. We led a big participatory process, interviewing a thousand people across the city on how they engage with city government. We asked what it would look like to change the legislative process so that the public can provide input earlier in the process, at a point when it can make a difference as opposed to during the final council meeting when things are simply getting approved. We took that feedback and worked with residents and the city government to develop a set of recommendations that are now being considered by the City Council.

We also just wrapped up a civic artists-in-residence program, where three artists were embedded in city government, focusing on the ways in which different departments engage the public, telling their stories about what it’s like to work in city government, and showing how city government functions on a very human level.

We recently launched a new project with a community gardening organization and the city’s planning and parks departments to train local residents on how to advocate for policy change. The hope is that in a year, we will have thirty to forty people who know when, where, and how to show up to public meetings and advocate for policies related to public space, green space, and connectivity in collaboration with city staff. An important distinction for us is that we’re not trying to direct what policies change. We’re trying to open the door to having more people involved in policy-making.

How do you build trust with community members, especially with traditionally marginalized communities or people who are skeptical about the role of government?

To create trust, we start with being vulnerable, showing up in spaces when we’re welcomed, and building relationships over time. I’ve been doing community development and civic engagement work for a decade in my city. I have a lot of relationships and people who trust me and this organization.

It also really matters who’s in the room when we’re building these programs. We generally have around 100 [people] involved in the decision-making of our organization. The boards for our civic transformation projects are generally made up of about fifty percent community members and fifty percent city staff, which creates a lot of opportunities for people to connect and understand things on a different level.

We also do not take positions on various issues, like those raised in upcoming bills. This practice has gotten us a lot of buy-in across the political spectrum and is really important for navigating a political climate. And at the local level, people don’t fall neatly into partisan lines when it comes to things like potholes, parks, housing, jobs, and transportation. We also have the added benefit of a nonpartisan local government – which means candidates do not run on political party affiliation. This is essential to how well our city functions.

Non-partisan local elections are really unique to city government. Can you explain how the non-partisan nature of your local elections impacts local governance?

Many local governments use non-partisan elections, but we are also a unique city in a lot of other ways. We are a consolidated city-county government, which makes our work very easy compared to working in a place where there’s a county government in addition to five different city governments. We are also a city that is open to thinking a little bit differently about local governance. While Lexington is a unique place, other communities could absolutely learn from our experience developing civic engagement projects.

You mentioned facilitated workshops. Who is moderating those events?

One of my staff members or I will facilitate, or we will partner with a community organization. Our philosophy on facilitation really comes out of the Kentucky Rural-Urban Exchange, a statewide leadership initiative and cultural organizing space that’s very different from political organizing. It has been incredibly influential for our organization to learn that place is more important than ideology. Processes that allow us to ground conversations in place, even the small conversations before a meeting, are really important to us. Talking about everyone’s favorite places to go in Lexington, asking how people’s kids are doing at the local school — we are very intentional about including those important chit-chats in our daily work.

If you were talking to other city leaders or government officials, what are the top lessons you’d share about your work at CivicLex?

A couple of things. I don’t really know if the work that we’re doing could be done in a city that’s larger than ours at the scale on which we’re doing it. I have a really deep interest in cities the size of Lexington and smaller, and the possibility for this work to be done there. But when I think about New York, how do you even scale? Building authentic relationships and a concept of place in a city like New York is challenging for me to think about. The human scale aspect really drives what we do because relationships are key — it’s how political change happens.

There are organizations very similar to us that focus on transparency and that’s great, but transparency without relationships, without a broad-based understanding of civic knowledge, without understanding how it all works, and without agency is pointless. For me, all of those things have to be done in tandem.

Relationship-based interventions must be grounded in a common understanding of civic issues and truthful, factual information while also recognizing that people have emotional reactions to these topics. For us, it’s really about making sure all the components fit together in a cohesive unit, to the point where we would rather not have people engage than have people engage and be disappointed.

How did you all engage with community members during COVID and how are you tracking data in your engagement efforts?

During COVID, we facilitated virtual conversations with people from different sectors, including the health department, about how COVID was impacting them professionally and personally. We then started organizing outdoor meetings in parks and ultimately started hosting in-person workshops again with masks. We did workshops around ARPA funding and pushed the city into meeting us halfway for a participatory budgeting process.

A topic we have been focusing on internally is data tracking. How do we ethically track the success of our work? Early on, we built a database that tracked individuals’ program participation, but because of ethical concerns, we shifted our focus away from individuals and toward specific areas and geographies. We also check in with council members to see whether they are getting more feedback on a particular issue.

About four months ago, we worked with our city’s Division of Planning to run the public input process for the update to Lexington’s comprehensive plan. From conversations with residents and accompanying surveys, we were able to capture well over 10,000 public comments on different issues across the topics covered in the comprehensive plan. We tracked geography down to the neighborhood cluster level so we could track how different areas engaged with different issues over time. Moving forward, we want to use this neighborhood cluster framework to measure our success in engaging specific geographies, because many things that happen in Lexington are place-based and neighborhood-based instead of citywide.

Are there other organizations with similar models that you know of doing work in civic engagement and power building?

There are not many organizations like us, which is really puzzling. I have a hard time finding them — I find different elements in different organizations in different places, but it is challenging to find other folks to share with and learn from. More place-based organizations that solely focus on building a healthy and informed civic fabric in a community are desperately needed.

Smaller places are what will determine the political future of this country. So we need to really focus on the civic health of our small towns, small cities, rural communities, and tribal areas.

The culture of all of our local civic fabrics creates our national political culture. Most people think about it the other way around, but that’s just because we’re so underinvested in the local, that the national dominates. If we invested more energy, money, and time into the local, then we would be able to make real progress on the challenges that we’re seeing. The level of alarm about our country’s civic culture is pretty high, but it is not high enough, particularly for smaller or rural communities. We owe it to people around the world to actually get our houses in order. To that end, we’re currently looking at ways to adapt our model to other communities. We’re starting with communities in Kentucky but are interested in places outside of here as well.

Are there any additional civic engagement models that you know about?

Yes. I think about the work Appalshop’s Letcher County Culture Hub is doing and has done, particularly within the cultural space. The Kentucky Rural-Urban Exchange and the new one that just launched in Minnesota are doing some really fantastic work. I want to emphasize that building a national network of organizations doing that work is something that’s really desperately needed.

One of my very favorite organizations is in Denver, called Warm Cookies of the Revolution. They were a big inspiration for me when I started CivicLex. I am also thinking of the Department of Public Transformation, which does a lot of this work through arts and culture.

We would like to thank Lindsay Zafir, Mark Schmitt, Maresa Strano, Jessica Tang, and Grace Levin for their incredibly helpful comments and editing support. This would not have been possible without them.