There is much that we have lost in our understanding of the forces and movements that led to the Civil War and shaped its aftermath. It’s not just Nikki Haley. Amnesia abounds.

Even during Black History Month, we rarely learn about one of the most important ways that Abolitionists – Black and white – challenged slavery before and fought for equality after the Civil War: by forming their own political parties and using fusion voting to build their own power to make change.

Both the names and the process are important to retrieve, not just for what they did but for what this may teach us about politics today. Like many other facts about our history that have been suppressed and forgotten, there is wisdom and potential in recalling them.

Americans have not always lived under a two-party political system. Throughout much of the 19th century, Black Americans and their allies had more room to maneuver, more ways to deploy their organizing power, and more ways to make their votes advance their agenda. The reason was “fusion” voting, which gave us a multi-party system in which it was easy for parties to form and inject new voices and issues into the political debate of the day.

In a fusion system, a minor party has two choices: run a stand-alone candidate, or cross-nominate someone who is also the nominee of a major party. The second choice allows the minor party to say “Vote for So-and-So, but cast your vote under our label and send a message of support for our values and issues when you do so.” This process of “fusing” on the same nominee makes it possible for all kinds of alliances to form, and it liberates smaller parties from the “spoiler” or “wasted vote” trap that otherwise inhibits their growth.

Fusion powered the abolitionist electoral strategy of the 1840s and 1850s. While the then-dominant parties, the Whigs and the Democrats, had anti-slavery factions, the leadership of both tried to keep these tensions submerged in favor of party unity. But instead of being stuck with voting for the “lesser of two evils,” anti-slavery forces had more options. So-called “political” abolitionists formed parties – the Liberty Party, Anti-Nebraska Party, Free Soil Party – each of these were simply groups of citizens (which is what a party is) who built an identity and an organization. Fusion voting was a tool that made their opposition to the “Slave Power” more electorally visible.

These new parties’ leaders and voters were mostly white people, but in some states, they included free Black men. They ran some stand-alone candidates for office, but they more commonly looked for favorable strategic opportunities to identify, elevate and “fuse” with anti-Slavery politicians – mostly Whigs but some Democrats – as a way to force abolition onto the national agenda. Perhaps the most famous example of the power of fusion was the election of Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, who won his seat in 1850 via the fusion of the Free Soil and Democratic parties in the state legislature.

Eventually, the Whigs collapsed due to internal tensions over slavery. A new party calling itself the Republican Party filled the vacuum with the various fusion parties merging into a force capable of winning elections in the northern states beginning in 1855. By 1860, this new party had elected a president, Abraham Lincoln.

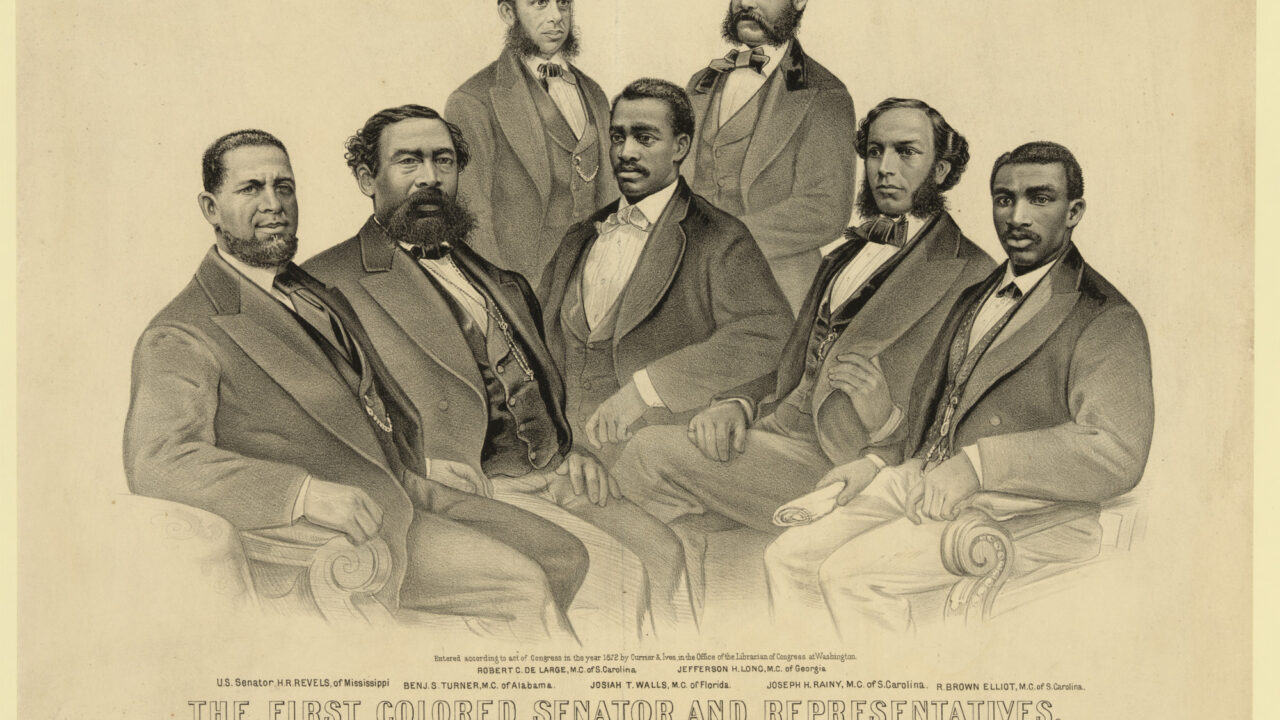

After the Civil War, fusion balloting continued as a central feature of American democracy. Minor parties – whether organized by farmers, workers, debtors, women, temperance advocates or others – each wanted to put their views forward. They were able to do so because ours was a multi-party democracy. Most dramatically there were a few states in which fusion permitted an astounding electoral coalition to emerge, an alliance between struggling white farmers who voted Populist and the newly enfranchised Black men who voted Republican. They differed culturally but they were united politically, especially in the Readjusters Party of Virginia and under the Fusionism banner in North Carolina.

In Virginia, the Readjusters Party called for the cancellation of Confederate war debt in order to help poor workers and farmers. It also sought to increase funding for public education, end the poll tax, and challenge the power of the plantation system and its banker allies. At their height, from 1877 to 1883, the Readjusters controlled the Virginia state legislature and elected its governor as well as two US Senators and members of Congress. Democrats only regained power by exploiting a race riot and violently suppressing the Black vote.

In North Carolina, a Fusion ticket of Republicans and Populists took control of the General Assembly in 1894. They moved quickly to pass a law making it easier for Black men to vote. Black Republicans gained seats at all levels of government as fusionists swept the election of 1896. White racists fought back, campaigning against so-called “Negro domination,” forming the “White Government Union” and holding a “White Supremacy Convention.” In 1898, blatant racist intimidation led to a drop in Black turnout. But what sealed the fate of the multiracial Republican-Populist coalition was the Wilmington Coup, when a mob of 2,000 white vigilantes rioted, attacking Black majority neighborhoods and driving the city’s elected multiracial leadership from power.

Jim Crow Democrats across the South understood the danger that fusion voting presented. And so, to ensure that another multi-racial, class-conscious electoral alliance did not materialize again, they banned fusion. In the North, Gilded Age Republicans had a similar dislike for fusion voting and the farmer-labor alliance between Populists and Democrats that it helped to sustain, and so they made the identical decision. They too passed state-by-state bans.

Today, fusion remains legal only in two states – Connecticut and New York. If you live anywhere else, you probably take for granted that the only meaningful choice you can make when you vote is between a Democrat or a Republican since third parties are essentially meaningless under our current rules.

But there is a quiet movement afoot to relegalize fusion in more states, led by advocates with the Center for Ballot Freedom. They argue that anti-fusion bans violate core rights of freedom of speech and freedom of association. Reviving fusion would be a boon for Black voters and other political minorities (racial or otherwise) who feel the current system fails to represent them. Black history shows us that a different system, a multi-party democracy, is indeed possible and, dare we say, necessary.

—

To learn more, see Liberty Power: Antislavery Third Parties and the Transformation of American Politics by Corey Brooks, Black and White: Land, Labor, and Politics in the South, by T. Thomas Fortune, and The Negro and Fusion Politics in North Carolina by Helen G. Edmonds.