Before the evening of November 8, 2016, I treated politics too much like a spectator sport — rooting for my side to win without getting out there to do the work to build power. As I chatted with friends in my upper middle-class enclave of North Arlington, Virginia, the week after Trump’s win, I was astonished by how many were experiencing the same emotional trauma that I felt, and how few of us had done anything to stop his victory. I knew that we had to do everything we could to make sure we never lost an election like this again.

But my friends were like me: overworked parents with overscheduled children. How could we motivate ourselves to carve time out of our overscheduled days for political activism? My instinct was that the answer lay in making political work accessible and fun — for parents and kids alike. Over the past four years, I have run Arlington Blue Families, an initiative that straddled the local Democratic Party and the new universe of pop-up grassroots groups. We have helped to channel suburban anti-Trump anger and desire for community into political organizing. We mobilized hundreds of volunteers — many of them suburban parents like me —to contact hundreds of thousands of voters with the goal of bringing Democrats back to power in Virginia and nationwide. And we learned that social engagement, and a focus on elections where we can make the most difference, are the keys to sustained and inclusive activism.

The week after the election, I started hastily compiling a list of emails of all of my local friends who I assumed to be as liberal and pissed off as I was. We held a sign-making party the night before the Women’s March. On the day of the Muslim Ban, several of us spontaneously drove to Dulles Airport with a fresh set of protest signs. And we started phone-banking to help candidates in a few local and congressional special elections.

But I barely had any sense of how best to channel our rage and energy. Looking for guidance, I wandered into the next monthly meeting of the local Democratic Committee. The featured speaker was a local representative who talked with evangelical fervor about how 17 state legislative districts currently represented by Republicans had just voted for Hillary Clinton. Winning all of these seats would be enough to flip the Virginia House of Delegates in November 2017 (we have off-year elections). The Arlington Democrats already had a family outreach program, Blue Families, that had sat dormant for a few years. I offered to head it up; all of the sudden, I had a social media platform and a small budget in addition to a vastly expanded email list.

Our first lesson in organizing was that anti-Trump rage wasn’t enough. It was easier to get volunteers when you had a great candidate to fight for — who also had a chance of winning. I recruited friends to host afternoon and evening phone-banking “parties” with teenage babysitting, but we struggled to get even five people to show up; some of those who did were turned off by making phone calls to strangers and didn’t come back. My friends and I needed a better hook for newbies, and we found it later that summer when we decided to adopt Danica Roem, a charismatic candidate in a far-flung Northern Virginia suburb about a 45-minute drive from Arlington who was vying to defeat the most homophobic legislator in the state to become the first transgender state legislator in U.S. history.

We ended up doing day trips to knock doors for Danica — and a few other Democratic challengers — about one weekend a month. I served as the primary organizer of these efforts, and we soon started seeing double-digit attendance. Over time, I recruited a small but dedicated group of fellow parents (between six and ten at any given time) who helped plan events and promote them within their own social networks. We experimented with a variety of ways to advertise, and learned to reach people through multiple platforms, both electronic and analog. The local Democratic Party communications infrastructure was pivotal: we could promote on its official Facebook page in addition to our own private group, hand out leaflets at their farmers market tents, and have the Party manage our volunteer list. But given that we wanted to reach people who may not have previously identified as active Arlington Dems volunteers, we also sent out our own email blasts and e-vites — and then made sure the Party knew who had attended. Many of our new volunteers became Party regulars, others counted themselves as members of other pop-up groups in the area, and still others just attended our events. Even early on, there was no territoriality and no pride of authorship — just a common interest in defeating Trumpism.

I have to give major credit to Jill Caiazzo, chair of the Arlington Democrats, for recognizing early on that these new groups were not a threat to the Party structure but rather the means by which to revitalize and replenish it. She allowed me and others within party leadership to straddle the grassroots and official party worlds, leveraging the Party’s human and financial resources while having the autonomy and flexibility that comes with being in the grassroots.

Soon, I got looped into the Virginia Grassroots Coalition, a nascent network of the grassroots groups that had formed in the region after Trump’s election. The coalition hosted guest speakers from more established advocacy organizations and local campaigns. And we batted around ideas for how we could add the most value, where to deploy our volunteer resources, and how to coordinate to make sure we weren’t all investing in one well-resourced candidate at the expense of three others who could win with just a little more help.

We learned that the best way to maintain engagement was to make sure everyone had a positive experience, which was only possible with some modicum of front-end planning: exchanging phone numbers, scheduling social time after the canvass, and coordinating with the campaigns to make sure everyone knew where to go and had smaller and more pedestrian-friendly turfs waiting for them at the canvassing launches. We also found it was important to provide frequent opportunities: something was always happening, even when an election wasn’t imminent. And we tried to plan evening canvasses in the neighborhood for those who couldn’t devote an entire day or weekend.

Of course, nothing fuels a movement quite like victory, and we got a taste of it — and the power of our efforts — that November when Democrats swept 15 of the 17 House seats needed to take the majority. Just as importantly, the somewhat uninspiring Democratic candidate for governor, Ralph Northam, scored a convincing nine-point victory by racking up massive margins in the very districts in which we were working. This convinced us that down-ballot races mattered.

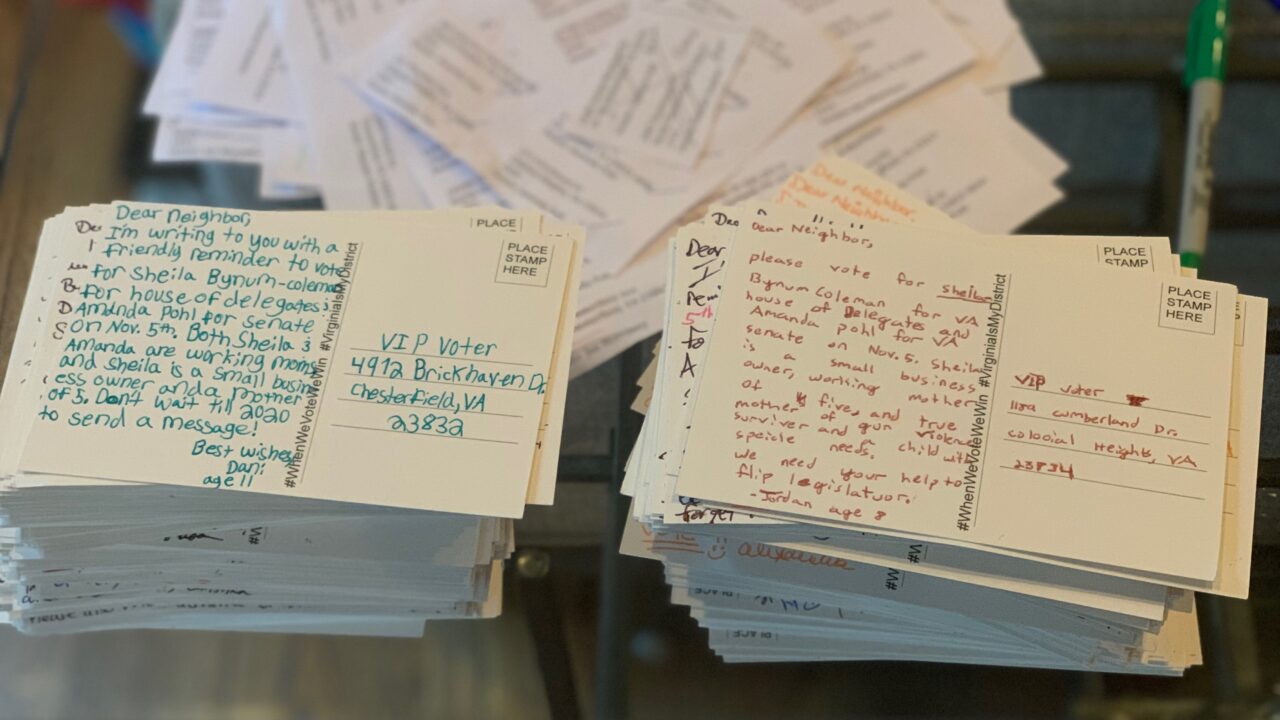

All along, I was struggling to refine my group’s core mission. We had invested in canvassing in 2017, but we quickly learned that it was a tall order for young families, and older kids needed to have a certain personality to participate. Then I discovered postcards. Here was something volunteers of every age and personality type could do. We knew that postcards were no substitute for in-person voter contact, although early data suggested that they could be effective if targeted to the right universe (low turnout voters), had the right message (positive), and were mailed at the right time (received just before it was time to vote). Most importantly, people enjoyed doing them with their kids, their friends, and a glass of wine. On the heels of our first postcard-writing parties, our recruitment efforts multiplied. Suddenly, we had a much larger universe of people to draw upon for our canvassing events. We also held the first of our soon-to-be-annual family-friendly potluck picnics in the backyard of an Arlington Dems volunteer, with a mix of kid-oriented activities and inspiring political speakers to keep the adults engaged.

We next turned our sights to extending the Blue Wave to the midterm elections. Arlington Blue Families joined many other grassroots groups in adopting Abigail Spanberger, a former CIA operative seeking to unseat a Trump conservative in the once deep red —but now very swingy — suburban Richmond district where I had grown up. The district was two hours away from Arlington (with no traffic), so we pitched our volunteers on hybrid tourist/activist weekends — do two canvassing turfs, spend some time enjoying the sights of Richmond, and swap war stories at a group dinner at the end of the day. Many people without young kids— empty nesters, retirees, and even pre-family millennials — appreciated the social vibe of our trips. So while we continued to be named Arlington Blue Families, we really became a wide tent covering families of all ages. In a sense, we became the Blue Family. And we helped deliver a win for Spanberger.

Because Virginia has off-year elections, we took almost no vacation after our 2018 triumph. Our obvious target in 2019 was taking the majority in the Virginia House and Senate and turning the entire state blue. This would enable us to pass a whole raft of progressive laws that had been bottled up by obstructionist Republicans for years. I also took a detour to help coordinate a postcard-writing effort for a friend who was challenging the local law-and-order prosecutor in the Democratic primary. I soon realized that there was another army of volunteers who want to write postcards at home, not just at postcard parties. I applied that lesson to the 2019 general election, setting up an online Google form and distributing tens of thousands of postcards that we wrote on behalf of 14 state legislative candidates — using addresses provided (and scripts approved) by the campaigns via Postcards4VA, another grassroots group that popped up in 2017. Most of our candidates prevailed, and we played a small part in delivering united Democratic governance to Virginia. And though we lacked the resources to measure the effects our postcards had, we felt confident that we had accounted for one of our candidates’ 83-vote margin of victory.

As 2020 dawned, and we looked ahead to the most important election of our lifetimes, Arlington Blue Families and the coalition of Virginia grassroots groups turned our attention to a nearby state where we had the opportunity to make a difference at all levels: North Carolina. We very much wanted to help with in-person voter registration early in the cycle. I feared that this could be incompatible with our family-friendly mission — it was a lot to ask busy parents to haul their kids four or five hours for a full weekend to stand outside a Wal-Mart with a clipboard. But by this point, a critical mass of volunteers was so deeply committed that they were prepared to travel any distance to win elections. Nearly forty DC-area resisters traveled to the Research Triangle the weekend of March 7-8, availing themselves of carpools and volunteer housing that we had arranged, and registered two hundred voters in two days. We were all set to send another thirty volunteers the following weekend, and planned to do one-to-two trips per month through the summer. We all know what happened next. Everything ground to a halt. No trips, no leaving the house, no in-person anything for the foreseeable future.

After spending a few days processing the loss of not just our voter registration initiative but the prospect of a normal campaign season, I realized that Arlington Blue Families already had the tools to help defeat Trump even in the middle of a pandemic: we would go all in on postcards. We took our 2019 effort and multiplied it, ultimately mailing more than 193,000 postcards and letters to voters in seven swing states. Along the way, a group of us was able to launch a separate postcard effort — this time looping in several DC-area grassroots groups — aimed at helping 12 key state legislative candidates in North Carolina, whose Democratic Party was a mere six seats away from flipping its State House and having a seat at the table for redistricting. We worked directly with the campaigns, which sent us spreadsheets full of voter addresses that we distributed to our hundreds of writers scattered across Northern Virginia, DC, and Maryland. Through these efforts, we built an army of nearly 1,000 postcard and letter writers — many of whom had never volunteered for a candidate before 2020.

Unfortunately, November 3 brought our first taste of defeat. While we played a small part in delivering Georgia, Michigan, and Wisconsin for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, we failed to flip North Carolina, win the Senate race, or make a net gain in the 12 state legislative races we had adopted. It was a stark reminder of the limits of our power; our pens and stamps couldn’t compensate for many other countervailing factors, including what in retrospect seems an ill-considered Party decision not to knock doors and conduct in-person voter registration after COVID hit. Of course, we barely had time to lick our wounds before we were moved to write 43,000 more postcards and letters for the Georgia runoff races.

So here we are at the end of four years of increasingly intensive grassroots activism, and there is no time to rest. We have to avoid the complacency that contributed to the midterm wipeouts in 2010 and 2014. We know there will be a backlash against Biden, but I’m confident that we won’t take our eye off the ball like we did a decade ago. With early indications that the GOP is doubling down on the toxic brew that led to the January 6 insurrection, our volunteers are under no illusion that the threats Trump represented have receded. My message: we lost Virginia badly in the 2009 governor’s race, and it ended up being a harbinger of 2010; now we have a chance to change that narrative by winning big in 2021— and demonstrating that The Resistance won’t rest.

We will stay engaged by slowly bringing back our pre-pandemic formula (postcard parties, canvassing field trips, other social events), figuring out how to make voter registration drives more social and kid-friendly, and leveraging our relationships within the local Democratic Party as well as our proximity to DC to incorporate hands-on civic opportunities (Capitol tours, family-oriented meet-and-greets with progressive leaders) for our volunteers. We now have an established platform to continue to increase our power and stave off the forces of fascism while finding more ways to make activism fun for kids of all ages. Sure, Virginia is now blue. But we don’t get any years off, and the threat of right-wing terror has exploded in our backyard.

Here are four key lessons to consider as we seek to make the progressive grassroots movement a permanent fixture:

-

We must continue to think of ways to make activism social and inclusive. Parents and their kids are a relatable face of a campaign (no one ever slammed the door in our faces when I was out there with my pre-teen daughter and teenage son). But everyone likes their organizing to be social, kids or no. We got many more registrants for canvassing events when we promised group dinners and other camaraderie with like-minded citizens.

-

We have an equity issue. I was able to devote as much time as I did because my kids are older (now 11, 14, and 18), my wife picked up a great deal of the parenting slack, and we had the resources to devote many weekends to activism. There is no doubt that our volunteers skewed white and affluent. But working-class families and families of color have even more at stake, and we need to do a better job making our activities more accessible to them. We started a stamp donation pool to bring more equity to our postcard writing efforts, but that’s just a start.

-

We need more information-sharing regarding what works and what doesn’t. Individual groups have a wealth of anecdotal evidence, but there is no centralized repository for our experiences. We don’t always have the resources to do conclusive and controlled studies, but we want to know the impact of our efforts and change course if there are better uses of our time. At the same time, grassroots groups need to use the tools we do have to measure our own effectiveness. It may be hard to measure how many additional votes we earned for our candidates, but we can certainly do a better job tracking what brings out the most volunteers.

-

We need to coordinate with parties but show less deference. It’s important to work with campaigns, parties, and well-established local groups to avoid duplicating efforts — or worse, working at strategic cross-purposes. But at the same time, grassroots groups should be unafraid to express our concerns if we think something isn’t working. As noted above, the Democrats abandoned in-person voter registration and canvassing as soon as COVID hit, but in short order it became clear that we could leave our houses safely if we stayed outdoors, wore masks, and maintained social distancing. I believe we paid a price in November as the GOP ended up out-registering and out-knocking us in local races where our candidates started with less name recognition than Joe Biden. Going forward, organizers should trust our instincts.

-

Grassroots and party organizations are not an either/or. Parties should find ways to embrace grassroots energy without trying to co-opt it, like the Arlington Dems have done. At the same time, grassroots leaders should consider joining their local party structure and changing it from the inside. Often, they could use the jolt of energy, creativity, and youth that the grassroots provide.

Read the issue: Debriefing the Resistance